- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How pottery played a significant role in shaping civilisations

Considered one of the oldest traditional crafts, pottery has played a major role in the social and cultural development of human beings. If one looks at the history of the earlier civilisations, one will know that each civilisation has produced its own pottery — a reason why ceramic vessels and potsherds dominate the list of objects normally found during all archaeological excavations....

Considered one of the oldest traditional crafts, pottery has played a major role in the social and cultural development of human beings. If one looks at the history of the earlier civilisations, one will know that each civilisation has produced its own pottery — a reason why ceramic vessels and potsherds dominate the list of objects normally found during all archaeological excavations. Although researchers have been studying in detail various types of pottery associated with different civilisations, the initiative got its momentum only recently, thanks to technological and scientific advancement in the field.

Since the area is vast, various types of scientific and technological analysis are needed before one reaches a conclusion. And here comes the role of coordination of researchers working on pottery in various regions. Keeping this in mind, a week ago, Chennai witnessed a five-day conference on ‘History, Science and Technology of South Asian Ceramics’ in which scholars from India as well as abroad discussed the significance of pottery, focusing on the hidden areas in the field.

At a time when India is witnessing the collapse of its traditional ceramic industry in favour of an alternative — metallic, more automated and less labour-intensive — the conference provided fresh impetus to the roots of an activity on the brink of extinction. Pottery is considered the mirror of a society and a study of various types of pottery associated with different civilisations will give an idea about how people lived and what were the ancient techniques they used to survive.

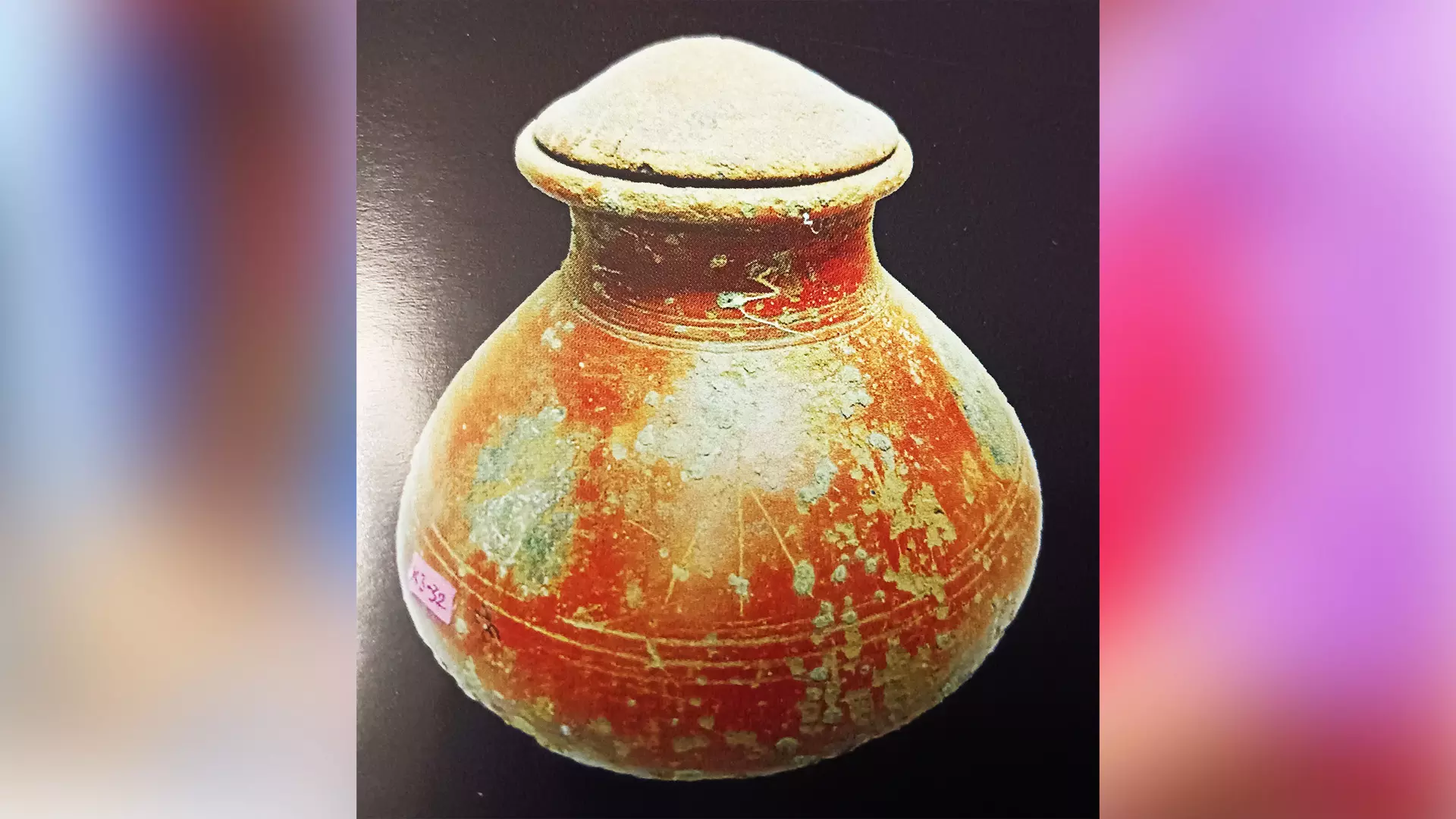

Ceramics belonging to the Harappan era.

During the Harappa Phase of the Integration Era (2600-1900 BCE), Indus ceramic production became quite diversified and involved a wide range of production modes, from household industry to mass production of common wares for use in the urban context, according to Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, who has been teaching archaeology and ancient technology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison since 1985. “There is also evidence for highly controlled workshops producing elite symbols of power, such as stoneware bangles. Various types of production were involved in these different workshops, including hand building, coil and slab construction, moulds and carved pottery,” he said, while speaking on “Ceramics in the Indus tradition: Technology, gender and Ideology.”

Mark Kenoyer has served as field director and co-director of the Harappa Archaeological Research Project since 1986. He has conducted excavations and ethnoarchaeological studies in both India and Pakistan, and of late, in Oman. He said the role of women in the making of pottery, particularly in the household, was significant but underrepresented. “There were female potters who made small-scale pottery for personal use during their free time. Male potters were involved in the large-scale production for regional and external trade. It is interesting to note that pregnant women were not allowed to use the potter wheels as the continuous strenuous activity would be dangerous for their health,” he said. Mark Kenoyer said the role of women in early ceramic technology of pottery-making, crucible clay preparation, lost wax modelling and mould-making and even early writing and ideological symbols has however been seriously underrepresented.

An exhibition of ancient pottery displayed as part of the conference.

When it comes to techniques, each region maintained its own style, even though some basic ingredients remained unchanged. The firing was also carried out in different types of kilns, including covered pit kilns, updraft kilns and high firing reduction furnaces. During the Late Harappan Phase (1900-1300 BCE), new production technologies, pottery styles and kilns were introduced.

With his two Indian potters, Mark Kenoyer made an experimental Harppan style kiln to check how it functioned. They produced 150 vessels, 100 figurines, bangles and beads, using the traditional kiln. “There does not appear to have been significant change in raw material sources for clay between the different periods at Harappa. Changes in firing technology may be linked to local accessibility of fuels but are more likely related to cultural choices about kiln structure, firing efficiency and the desired end result,” he said. However, changes in vessel form can be linked to cultural choices regarding food preparation techniques, food preference and technological innovation.

Knowing the sequence of ceramic activity is important when it comes to the study of ancient pottery. In Tamil Nadu, the recent excavations with intensive explorations provided certain basic information on the ceramic sequences. More than 10,000 graffiti inscribed potsherds and 1,500 Tamili (Tamil-Brahmi) inscribed potsherds have been unearthed from various parts of the state to date. The inscribed potsherds were engraved with personal names on the shoulder portion of the pot, a social context marker. “There is a region-specific ceramic such as russet-coated ware, which are found only in Kongu region of Tamil Nadu. However, its presence in other regions reflects its commercial or cultural contacts. So, it is important to understand the contextual position of each ware and their stratigraphical and chronological settings based on the data collected both from excavations and explorations,” said K Rajan, academic and research adviser, government of Tamil Nadu, while presenting his paper on ‘Ceramic chronologies of Tamil Nadu: An overview,’ that he co-authored with R Sivanantham.

In Tamil Nadu, according to Rajan, who has spearheaded many significant archaeological excavations, the recent excavations conducted at Pattaraiperumpudur, Vadakkupattu, Perumbalai, Budhinattam, Kodumanal, Vembakottai, Keeladi, Alagankulam, Adichanallur, Sivagalai, Korkai and Thulukkapatti have yielded certain basic information on the ceramic sequences.

A graffiti-engraved pot excavated from Tamil Nadu's Perunthal.

Researchers have identified the existence of human habitation in a site based on the potsherds and ceramic remains excavated from that region. Recent excavations at Vadnagar in Gujarat have identified certain ceramic traditions dating back to the 1st millennium CE. This period, according to scholars Abhijit S Ambekar and Ananya Chakraborty, witnessed the appearance of new wares such as Red polished ware, Coarse grey ware, Black burnished ware, and among imported ceramic types – Torpedo jar sherds and turquoise glazed ware (both non-Indian in origin). “Among these, the latter distinct ceramic types indicate a relationship of the Indian subcontinent with the Western world (including Mesopotamia) and its overall cultural and economic connections through seaborne trade,” said Abhijith, who is a superintending archaeologist at the Archaeological Survey India’s Excavation Branch V in Vadodara.

The amount of torpedo sherds discovered across various locations and cultural layers at the site highlights a considerable demand and supply to Vadnagar.

Torpedo jars, according to Abhijith, had likely served as vessels for transporting liquid commodities such as wine, oil, or other valuable food items over long distances. “The presence of such a large number of torpedo jar specimens not only entails substantial import demands but also implies the affordability of the inhabitants residing in an urban centre such as Vadnagar,” he said. Excavations at Vadnagar show a continuous human occupation of more than 2,750 years, and archaeologists believe that it is probably the sole example in India having such a long continuous habitation at one particular location despite having adverse environmental conditions. A brilliant rainwater conservation system, introduced by the local people, is said to be the main reason behind the uninterrupted human habitation.

While experts shared their knowledge on pottery and associated materials, a question was raised about whether one should wash the ceramics or not. Stephen Koob, former conservator of Corning Museum of Glass, said “yes”. “Most ceramics are exposed to water ever since they are buried. So, there is nothing wrong in washing the ceramics. Some ceramics need to be cleaned but some don’t need a wash. One should decide on this based on the quality of the ceramics. A fragile one needs a different treatment. A fruitful coordination between the conservationist and the archaeologist is necessary in this case,” said Stephen Koob, who is the author of Conservation and Care of Glass Objects.

The 3rd International Conference in Commemoration of Padma Shri Awardee and renowned epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan was organised in collaboration with IIT Gandhinagar, Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology and IIT Madras at IC & SR, Chennai. The idea of the conference was to bring together a wide range of experts. “We included archaeologists who have had extensive experience of south Asian ceramics, and archaeological chemists with expertise in the elemental analysis of ceramics. In addition, we included established ethnohistorians and ethnoarchaeologists of south Asian ceramics, alongside knowledge keepers who brought their lifelong and inherited skill, expertise and knowledge,” said Alok Kumar Kanungo, academic coordinator for the conference and faculty at IIT Gandhinagar who has conducted research on the archaeological and contemporary crafts related to glass, beads-bangles, ceramic and iron. More than 40 scholars shared their ideas and experiences during the conference.

Massimo Vidale’s experimental reconstruction of a Greek kiln of the 5th century BCE, carried out at the Laboratory of Experimental Archaeology of the University of Padova, was based on faithful coeval iconographic evidence. He and his team found that the kilns used in Greece and southern Italy between the 6th and the 4th centuries BCE have important similarities with Harappan pottery kilns. “The reason why Iron Age pottery kilns of early Europe and the early Bronze Age kilns of south Asia are so similar are to be looked for in the relationships of production between producers and consumers in the context of ongoing urbanisation,” said Massimo Vidale, an expert on Bronze-age technologies and trade relationships between the ancient Indus and Mesopotamian civilizations. “Probably in both cases we are dealing with families of potters making ceramics for a restricted group of families, only a segment of the overall society, and not for an extended market. The structure needed for making high quality vessels, even at the cost of reducing the volume of the output,” he added.

A group makes a traditional kiln to fire the pots. Experts say changes in firing technology may be linked to local accessibility of fuels but are more likely related to cultural choices about kiln structure, etc.

Every excavation brings in a lot of pottery of different shapes and sizes, but there is a visible decline evident in pottery production and their uses from Malti Nagar’s (a pioneer in the field of ethnoarchaeology in South Asia) ethnographic studies done in the village of Parla to today’s potters in Gilund in Rajasthan, according to Amrita Sarkar. Parla and Gilund are approximately 100 km apart and share the same ecological condition and these two distinct sites have been placed under the same cultural zone even during the chalcolithic period.

“Considering the trend of pottery decline at Gilund, it would be right in concluding that other potters residing in villages under the same ecological conditions and facing economic and social changes brought in by globalisation face the same predicament as potters in Gilund. It is possible that in the next 15 to 20 years, production of ceramic vessels by these small indigenous local potters will totally die out and pottery manufacturing will be restructured into a centralised industry mass-producing one or two types of vessels, such as bing jars or pots that people might still need to store liquid and keep it cool and which might no longer provide us with the insight into the lifestyles of generation past that is very basis of ethnoarchaeology,” said Amrita Sarkar, assistant professor in the Department of AIHC and Archaeology in Deccan College Post-Graduate & Research Institute.