- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Pithora art’s folkloric passion is being kept alive

In the crisp January light, Sakshi Tribal Arts Gallery near Lal Bagh Palace in Indore shone with indigenous creativity. Surrounded by colourful Pithora and Bhil paintings, Sakshi Bhaydiya, a 25-year-old artist momentarily halted her traditional sewing work—her hand tracing a large Pithora painting, revealing her profound connection to her cultural roots—a silent dialogue between artist...

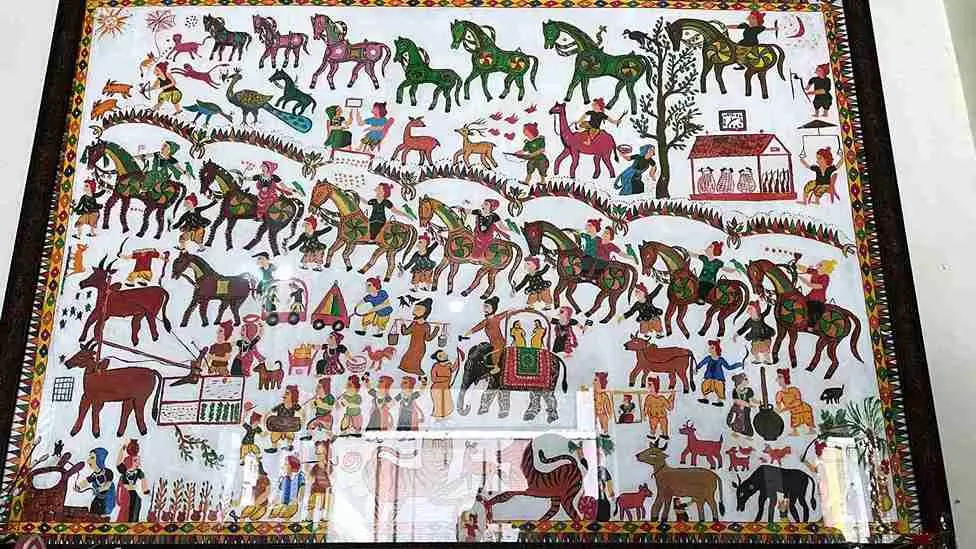

In the crisp January light, Sakshi Tribal Arts Gallery near Lal Bagh Palace in Indore shone with indigenous creativity. Surrounded by colourful Pithora and Bhil paintings, Sakshi Bhaydiya, a 25-year-old artist momentarily halted her traditional sewing work—her hand tracing a large Pithora painting, revealing her profound connection to her cultural roots—a silent dialogue between artist and artwork that spoke volumes about her heritage. “This is Pithora art,” she says, drawing attention to the rightmost horse of the seven that fly across the 2 by 3 feet canvas—“carrying Ghukka Ganesh—one of the deities we worship in our hometown Jobat, in Madhya Pradesh's Alirajpur district.”

The last horse, paradoxically painted first, represents more than just an artistic technique. “It's a portal to a vanishing cultural narrative, a visual language that speaks of the Bhil and Rathwa community's deepest spiritual connections. Each horse carrying a god represents—a glimpse into our world where art is not just decoration, but a living, breathing ritual,” she says. Bhaydiya is the first female artist to transform Pithora art from a male-dominated ritual practice to a canvas-based art form, critically preserving and popularising this traditional artistic heritage.

Eloquently likening art to an ocean of life, Dr. Vasudev Sharan Agrawal hailed as the pioneer of Indian folk art, observes that the resonant mosaic of our history and culture draws deeply from the essence of folk traditions. According to him, the roots of our agriculture, art, science, literature, and the myriad forms of artistic expression are intricately interlaced with the lives of the Indian folk. Our languages, the joy embodied in our festivals, and the rhythm of our dances, music, and storytelling—all find their origin in this cultural reservoir.

The last horse, paradoxically painted first, represents more than just an artistic technique.

Though passionate about Pithora paintings since childhood, Bhaydiya only began professionally creating them six years ago. She says, “Pithora is a ritualistic, folk art from Chhota Udaipur at the border of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, typically painted on house walls. By painting on canvas, I want to share this art form that's on the verge of extinction. I want to introduce it to people who can't visit the village, ensuring its legacy continues beyond local walls.”

The fascinating history

The Pithora paintings emerge from the soul of tribal communities—Rathwa, Bhil, Nayak, and Tadi—their brushstrokes tracing a lineage thousands of years old, descending from cave paintings near Koraj-i-Dungar. More than mere decoration, these illustrations are sacred narratives carved into the liminal space between the verandah and kitchen—a periphery that holds profound spiritual significance. Here, Pithoro, the benevolent deity of sustenance, watches over scenes that pulse with life: spectral ghosts, divine figures enmeshed in cosmic sagas and lovers—both human and animal—caught in passionate acts. Similar to Warli and Saora tribes, these paintings are rarely decorative, instead focus on the layered composition of mythological landscape, spanning Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh.

In his book Madhya Pradesh Ki Lokkathayen: A Collection of Folk Tales from Nimadi, Malvi, Bundeli, and Bagheli Cultures, author Vasant Nirgune delves into the profound significance of folk art and its cultural roots. “I believe the origin of folk art lies deeply embedded in Adyam culture,” he asserts, emphasising the gravity of traditional art forms. “The work of folk art is serious and cannot be taken lightly.”

Nirgune further highlights the universal impact of folk traditions, stating, “The folk tales that we see today have been the foundation of world literature, music, society, and art. I have observed that many unconventional works remain incomplete without the addition of a colour line, a practice rooted in deep faith, dedication, and commitment.” He elaborates, “Folk art penetrates every facet of our lives, much like fine lines, and adds beauty and depth to our existence. It is not a mere application of colour; it is a serious and meaningful pursuit.”

The choice of colours

In rural Nimaad, paintings often beautify the walls of homes, thriving on cyclical creation and destruction. These paintings narrate the region's cultural essence and are intricately tied to its festivals and rituals; serving as visual companions to worship, discussions, folk songs, and storytelling throughout the year. In folk painting, colours often embody freedom and creativity. While artists explore spirited palettes, established customs guide the choice, combination, and application of colours, shapes, and lines. Paintings may alternate between multicoloured and simpler palettes, adhering to these rules. Even the medium and techniques are predetermined, ensuring each piece aligns with its ancestral lineage.

Folk artists meticulously preserve the practices handed down through generations. From the way their elders painted mountains and festival scenes to the methods of mixing colours, preparing brushes, selecting walls or canvases, and layering the background, every step follows time-honoured conventions. This disciplined adherence ensures the authenticity and continuity of their art.

Pithora is a ritualistic, folk art from Chhota Udaipur at the border of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, typically painted on house walls.

Bhaydiya says that while she uses acrylic on canvas for contemporary work, the ritual paintings follow an ancient, intricate method. The Anushthan (process) begins with coating a raw, unpainted, wall in a mixture of cow dung, lime, stone, and mahua-based alcohol. The colour palette is a paragon of natural ingenuity. Orange flowers transform into orange hues, turmeric yields sunny yellows, charcoal creates deep blacks, and lime provides pristine whites. These pigments are crafted swiftly, emerging within mere hours, each colour a tribute to the tribe's intimate connection with their environment.

the art now persists only through a few passionate artists committed to safeguarding its endangered heritage.Prepared from natural colours and cow dung, these folk paintings include iconic motifs such as Jirauti (also known as Sanjha Phooli), Naag, Narvant, and Gordhan. Scholar Shri Naam Narayan Upadhyay has classified Nimaad’s folk paintings into two categories, the ones in colour and the ones made with cow dung. Paintings made with colours include motifs such as Jirauti, Naag, Kuldevi, Dussehra, Bhai Dooj, Diwali, Hande, Mandra, Saraswati, Ganpati, Sati, Santia, Swastik, and Chauk Kalash. On the other hand, paintings crafted from cow dung bring to life designs like Sanjha Phooli, Narvant, Gordhan, Gyaaras Khopdi, Gudna Aakratiyaan, Paglaya or Padda Chinna, and Mehndi.

In folk paintings like Pithora, colours convey the essence of deities, nature, and the universe, seizing the rhythm of life itself. It is not just an element—it's the soul of the painting. For instance, Jirauti Devi often features a distinct yellow. Folk artists typically use unadulterated colours, preserving their purity and intensifying their psychological impact. These raw shades profoundly influence the human mind and body, creating a visceral connection between art and the viewer. Such works, often created in homes, have long embedded the emotional resonance of colours into human consciousness.

Traditionally, rural artists derived pigments from natural sources like soil and water. However, over the last five decades, the rise of ready-made paints has reshaped the folk art landscape. These modern materials have added durability and a new dimension to age-old traditions while preserving their charm and narrative depth. Whether in the bold strokes of Nimal, the intricate patterns of Malwa, or the rich motifs of Madhubani, folk paintings overflow with the colours of life. Each colour tells a story—joy, anger, love, or even conflict—grasping the spectrum of human experience and emotions.

The Pithora ritual

Folk literature is abundant in Nimaad, and its festivals are incomplete without the melodic strains of its folk traditions. Even in moments of simple joy, such as a farmer rejoicing over finding a lost buffalo, or be it life milestones like maan, mundan, sagai viva, or celebratory festivals like Holi and Gangaur; the songs dedicated to Saint Singhaji resonate through the village.

Padma Shree recipient Bhuri Bai, a revered icon of Bhil tribal art, recounts Pithora journey steeped in ritual and reverence. “For one and a half to three consecutive days, village men layer a sonic landscape, a dhag—traditional folk songs and chants—accompanied by the rhythmic beats of the drum. As these musical layers merge, Pithora artists tirelessly paint the walls, transforming them into living narratives of tribal culture and spiritual expression.” She insists that the process has to be continuous and is thus painstaking.

Padma Shree recipient Bhuri Bai, a revered icon of Bhil tribal art.

Though her artistic journey began at five, painting hut walls during festivities in Jhabua, she treads a delicate line of cultural respect. Bound by tradition, she acknowledges that Pithora Art is a male-exclusive ritual. Her own work celebrates Bhil tribal life through figures, animals, trees, and gobari pooja, deliberately avoiding Pithora Baba and his horses to honour community sentiments. While she celebrates peers like Premapati from Alirajpur and Siliya from Gujarat, Bai is unequivocal: women imitating Pithora art on canvas risk diminishing its sacred essence—a boundary she carefully maintains in her own transformative artistic practice.

The art narrative

In Alirajpur, Pithora paintings traditionally adorn raw mud walls with a distinctive style. Bhaydiya highlights various elements in her Pithora painting, noting, “Pithora art is devoted to Pithora Baba, the principal deity of the Bhil tribe. It is however a ritualistic painting; depicting seven horses soaring across the sky, carrying celestial beings. These Gods and Goddesses are worshipped with different beliefs.” She adds, “Rani Kajal Mata, the Goddess of Rain, symbolises fertility and agricultural abundance, invoked to bless the lands with life-giving waters. Gods like Kalu Rana, Indal Dev, and Patla converge scenes of daily tribal existence.”

From right to left, the artwork unfolds—revelling in the profound synergy between humanity, nature, and spiritual beliefs. Lions prowl near forest edges, elephants stand as regal witnesses, while scenes of traditional dance, well-drawing, and grain grinding illustrate the rhythmic consonance of tribal life. Bhaydiya says, “Techniques have evolved across generations, but the fundamental essence remains consistent. While contemporary artists like me might subtly modify character representations, the core cultural and spiritual identity of the artwork endures.”

The lengthy undertaking

Bhaydiya explains that working with natural colours is a meticulous and time-intensive process, whereas using acrylic paints on canvas significantly reduces the time required. “The duration largely depends on the size and details of the artwork,” she says. “For example, an A4-sized painting with acrylics can be completed in 2-3 hours, while a larger 2x3 feet canvas takes around 2-3 days.” Reflecting on the jacket she designed for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Bhaydiya explains, “On clothing, we primarily showcase our traditional art through depictions of Bhil lifestyle. We don’t paint our gods on fabric—it’s a principle of our culture. The art form we bring onto fabric is called Bhil Pithora, which focuses on Bhil life and traditions.” She adds that Pithora deities are not depicted on clothes or regular walls, as such spaces could disrespect their sanctity.

When asked about the Pithora painting displayed in her gallery, she clarifies, “This is a replica in acrylic, which can be framed and kept in homes or temples to bring positive energy. Only those who understand Pithora Baba and the value of his blessings tend to buy this artwork. Others typically request portrayals of Bhil lifestyle instead.”

Bhagdiya concludes by sharing her vision of introducing Pithora culture to the world. “I want to guide women and society in a new direction—that’s why I paint,” she says. Reflecting on traditional norms, she adds, “My uncle often recalls how women weren’t as active in this art before. Our community used to adhere to the idea that women shouldn't create Pithora paintings. But he also acknowledged that there’s no restriction against it.” She further explains, “When painting with acrylics, you don’t need to recite any mantras—it’s about replicating the original art for a purpose, making it more accessible while preserving its essence.”