- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Northeast is breaking myths, challenging the cliches about Northeast

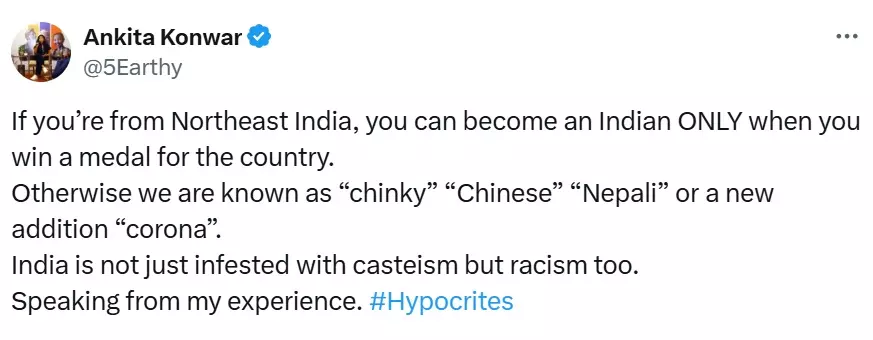

“People from Northeast can become Indian only when they win medals for the country (in Olympics),” actor-model Ankita Konwar wryly wrote in a social media post after Mirabai Chanu bagged the Olympic medal in Tokyo in 2020. Those commenting on the post extended vehement support for the statement.A galaxy of young talented youth from various northeastern states have found in visual arts...

“People from Northeast can become Indian only when they win medals for the country (in Olympics),” actor-model Ankita Konwar wryly wrote in a social media post after Mirabai Chanu bagged the Olympic medal in Tokyo in 2020. Those commenting on the post extended vehement support for the statement.

A galaxy of young talented youth from various northeastern states have found in visual arts a means, other than sporting laurels, to claim so-called mainstream India’s mind-space.

Their extraordinary stories of triumph and disaster weaved around their own community settings are creating a buzz around the film festival circuits, forcing the nation to look at the north-east from a newer prism.

Assamese filmmaker Rima Das opened up a new horizon with Village Rockstars. The film, written, edited, co-produced and directed by Das, captures the story of a 10-year-old girl, Dhunu, who lives in a small village in Assam and pursues her dream of owning a guitar and forming a rock band despite the woes and misery of her and her widowed mother’s daily existence, worsened by natural calamities. It was a courageous pursuit for happiness against all odds.

In a way it was the story of the resilience of the region that has thrived, despite conflicts and turbulent political atmosphere.

“A young girl and her mother’s woes and misery are not music to the ears but their spirit is,” the synopsis of the film reads, almost articulating the mental makeup of one of the country’s most militarised zones.

The film became India’s official entry to Oscars 2019 in the ‘Best Foreign Language Film’ category.

More importantly, it broke the glass ceiling.

The same year, Pradip Kurbah, a film-maker from Meghalaya, grabbed national and international attention with his Khasi movie Iewduh, which means market in Khasi. The film won the Kim Ji-seok Award at the 24th Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) in 2019, becoming the first Indian movie to get the coveted honour.

Iewduh won the Kim Ji-seok Award at the 24th Busan International Film Festival in 2019, becoming the first Indian movie to get the coveted honour.

The 94-minute film again centered around the lives of common people and their stories, shot entirely in Shillong’s oldest and largest traditional market.

More and more unique stories soon started to be churned out, showcasing the linguistic and cultural diversity of the region and unravelling a treasure trove of human and humane stories.

Aimee Baruah’s Dimasa-language movie Semkhor, Sounak Kar's Galo-language film Peta Dochcho and Khasi director Nicholas Kharkongor’s Axone in Hindi and English to name a few.

Assam-based filmmaker and film historian Parthajit Baruah says these talented filmmakers and their works have started changing the mindset about the region.

“They are respected, not categorised as north easterners. They are the young voices of the Northeast,” adds Baruah, the author of several books on films including Face to Face: The Cinema of Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

In his book A History of India's North-East cinema: Deconstructing the Stereotypes, Barah examined the role of Bollywood in the construction and misrepresentation of this region in popular Hindi cinema.

Remember radio jockey Amarkant Verma played by Shah Rukh Khan in the 1998 romantic thriller Dil Se giving facial description of a mysterious lady he glanced at Assam’s Haflong station, and intensely fell in love.

“…Kaali, gehri par choti se aankhen, uche uthe hue gaal, chapti si naak jeysen jaldbazi mein laga dei geyi… (black, deep eyes, perforated cheeks, a flat nose which appears to have been stuck on the face hurriedly)” Thus, he described Meghna, played by Manisha Koirala, to his listeners.

The well-intended film set against the backdrop of insurgency in Assam, unwittingly normalised racist taunts, passed off as banter, people from northeast often face outside the region for their physical features.

The more recent action thriller, Anek, directed by Anubhav Sinha, is another instance of Bollywood inadvertently promoting the stereotype about the Northeast due to lack of research and proper understanding of the heterogeneous region with diverse socio-political milieu.

“The film portrays the north-eastern part of India as a militarised and exotic terrain, where terrorist organisations are causing widespread destruction. The narrative centres on the obstacles encountered by a covert government law enforcement operative dispatched to north-eastern India with the objective of negotiating a peace accord between the government and insurgent factions.

“In an attempt to depict the insurgency situation in the region, the film portrays the region as a perilous location for travel and labour. The narrative homogenised and exoticizes the entirety of the north-eastern region as a war zone,” points out Luku Morang, a professor and film critic.

Insurgency has been the recurring theme since the days of Dev Anand starrer Ye Gulistan Hamara, released in 1972, in the limited portrayal of the region in Hindi cinemas, the soft power that shapes popular Indian culture and perception.

Insurgency has been the recurring theme since the days of Dev Anand starrer Ye Gulistan Hamara.

Prior to this young brand of filmmakers from the region, there had been few initiatives by film-makers from Northeast, barring a few exceptions such as Bhupen Hazarika, Bhabendra Nath Saikia and Jahnu Barua, to showcase the region, its people and culture to a larger Hindi audience.

On the other hand, even the award winning regional-language films like Halodhia Choraye Baodhan Khai (Assamese) or Matamgi Manipur (Meitei) did not create much buzz outside the region. Moreover, film making started with Joymoti, an Assamese film released in 1935, has a long history in the region, the art form was limited largely to two regional languages--- Assamese and Meitei.

As a result, the northeast did not get proper projection in the mainstream visuals.

Things started to change with the transition of film making from celluloid to digital.

“The digital mode has significantly reduced the production cost and infrastructure need of a film, allowing the filmmakers to experiment without bothering much about the commercial viability of a good story or a theme. This has led to the proliferation of independent filmmakers,” Guwahati-based filmmaker M Maniram told The Federal.

“In celluloid, before taking a shot one had to think several times so as not to waste a reel, which used to be very costly. Now you have the luxury of taking shots from various angles and then pick and choose according to the need at the editing table,” he pointed out.

The visibility quotient or possible exposure of a film has also increased by the YouTube and OTT platforms. More efforts have been made to include films from the region in film festivals. The India Pavilion at Cannes 2023 brought actors, filmmakers, and industry experts from the northeast.

“Earlier, a filmmaker had to solely depend on the distributors and the film hall owners to screen a movie. Now, if there is no taker one can just upload the work on YouTube,” Maniram added.

Driven by the praise that films from the region have garnered for their stories rooted in authenticity of situations, characters and their lives, and presenting a stark contrast to the stereotyping that happens in Bollywood, the so-called mainstream cinema also seems to be making course-correction. Arunachal Pradesh’s Chum Darang in Badhaai Do played a character minus the stereotypes that used to come to her earlier.

The new breed of young filmmakers from the region are taking full-advantage of the technological gain and changing mindsets, even if narrowly, to challenge the stereotype Bollywood had set.