- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Kashmir’s Baba Wayil village has kept dowry, gold, expensive wazwan out of wedding menus

Saima Jan, a 28-year-old woman from Baba Wayil, a village in Kashmir’s Ganderbal district, has butterflies in her stomach. She gushes at the mention of her upcoming wedding in July 2024. Just like all other would-be brides, Saima is both excited and apprehensive of what life after marriage would be like. But her similarity with other brides ends at that. Saima is not going mad shopping....

Saima Jan, a 28-year-old woman from Baba Wayil, a village in Kashmir’s Ganderbal district, has butterflies in her stomach. She gushes at the mention of her upcoming wedding in July 2024. Just like all other would-be brides, Saima is both excited and apprehensive of what life after marriage would be like. But her similarity with other brides ends at that. Saima is not going mad shopping. The only thing she is looking forward to is a happy union with her groom-to-be, a walnut trader, and to seamlessly adjust with his side of the family.

In Baba Wayil, young women and men are only focused on their unions and not the extravagant events weddings have come to be. The families too do not lose sleep over meeting marriage expenses since they entered into an agreement to denounce dowry and keep weddings a simple affair.

“We are not compelled into anything. We have the freedom to make choices, and we exercise our rights without hindrance. Personally, I feel proud in being a member of this society and culture,” Saima told The Federal when asked if this agreement has hampered her dreams of a ‘big, fat wedding’ in any way.

In Kashmir's Baba Wayil, families that accept or give dowry are ostracised.

Supporting the decision of Baba Wayil to say no to dowry, Saima said the dowry system has dehumanised women and turned marriages into transactional arrangements which focus on exchanging goods rather than sharing love and respect.

Saima’s wedding will therefore be a modest affair in keeping with the village’s agreed upon guidelines. The ceremony is set to take place at her parents’ residence with a few attendees. On the appointed day, the groom, accompanied by only four persons, will visit Saima’s home. Her bridal attire will consist of a simple frock-shalwar and a veil, contrary to the expensive fancy bridal dresses that women go for in Kashmir despite its unaffordable price range.

Dowry and unfair burden of marriage expenses on the women’s family is a growing concern in Kashmir.

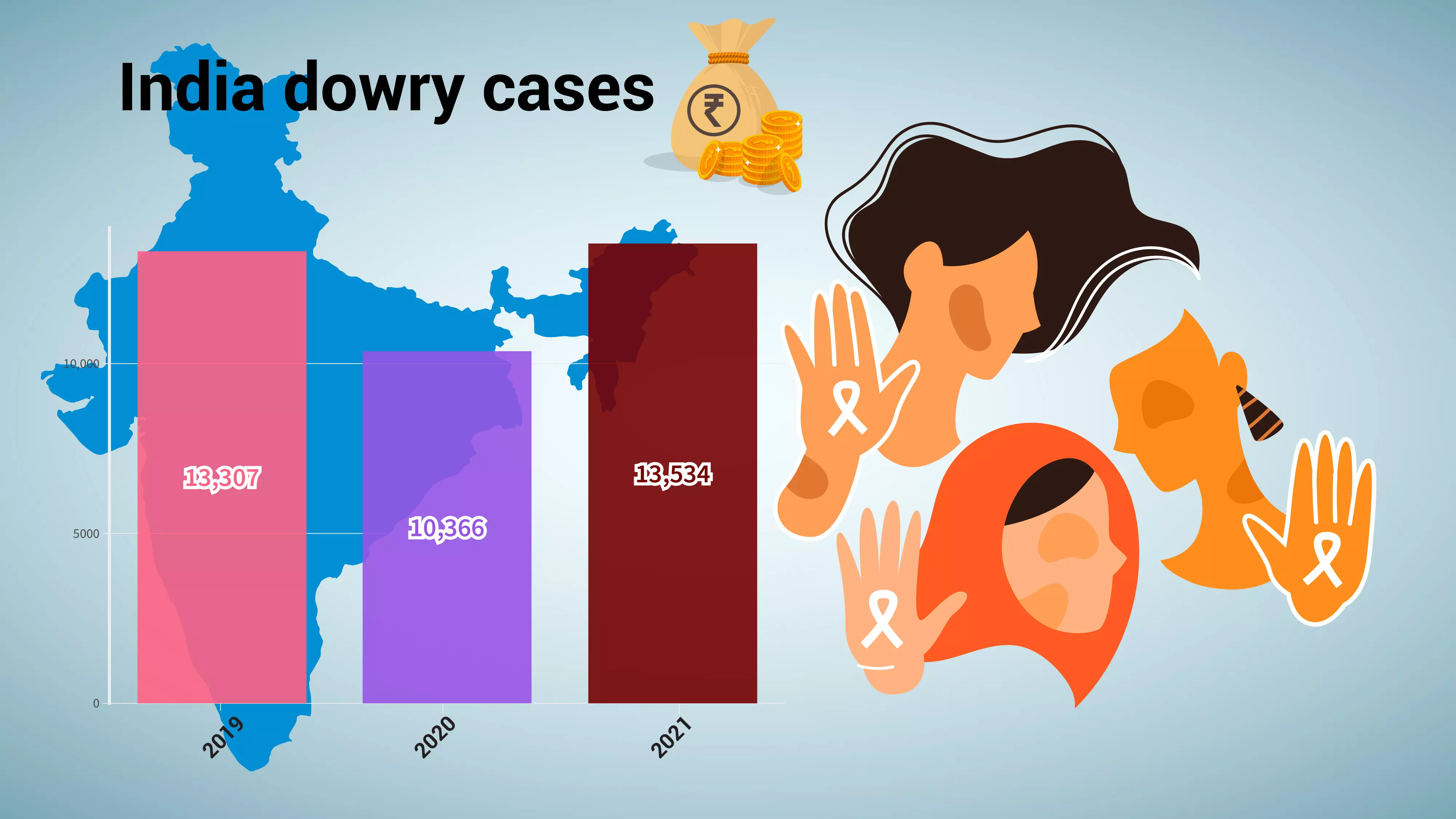

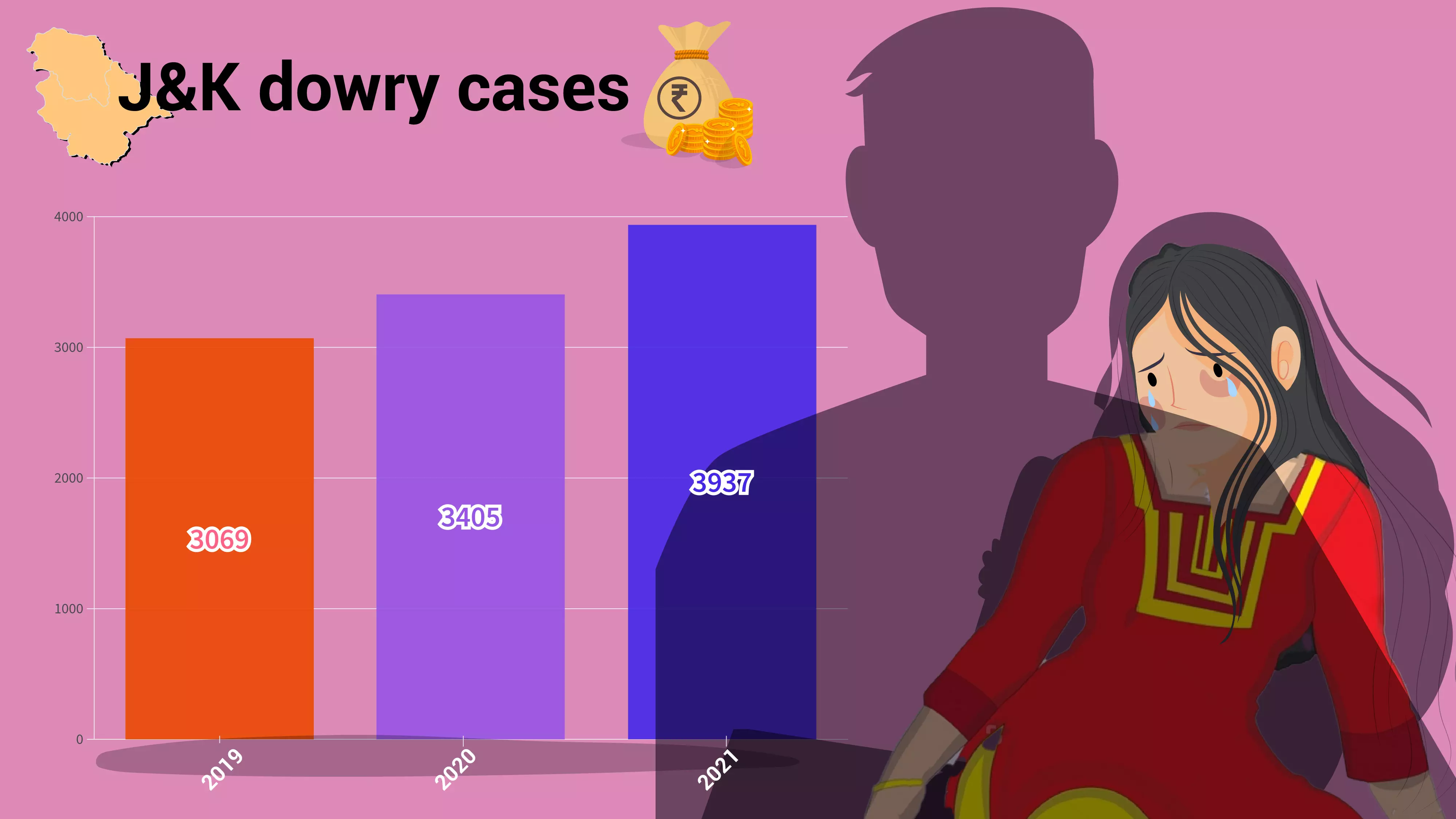

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Kashmir saw a 15.2% growth in crimes against women in 2021. The Valley reported 3,937 cases under Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 in 2021, 3,405 cases in 2020 and 3,069 in 2019, as against the national tally standing at 13,534 in 2021, 10,366 in 2020 and 13,307 in 2019.

Breaking the trend

But Baba Wayil stands as an exception.

The dowry-free village, dotted by mostly newly constructed houses with a few older mud houses interspersed in between, in central Kashmir’s Ganderbal district is around 35 kilometres from Srinagar. The nondescript village stands out on Kashmir’s map for organising simple weddings without exchanging any dowry. With a population of 1,800 residents and about 300 households, the village, whose inhabitants are mostly into businesses related to walnuts and shawls, has only strengthened the tradition that started around four decades ago. The approximate expenditure for the wedding is Rs 1 lakh from the bride’s side and Rs 2 lakh from the groom’s side.

It is said that 750 years ago, a revered Sufi saint named Syed Baba Abdul Razzaq journeyed from Baghdad to central Kashmir. Seated at the foothills of Guttil Bagh, he preached and propagated Islam, and the village was named after him. The majority of residents in this village belong to the Shah caste, who are believed to be direct descents of Prophet Muhammad. The villagers say Islam is against dowry and so are they.

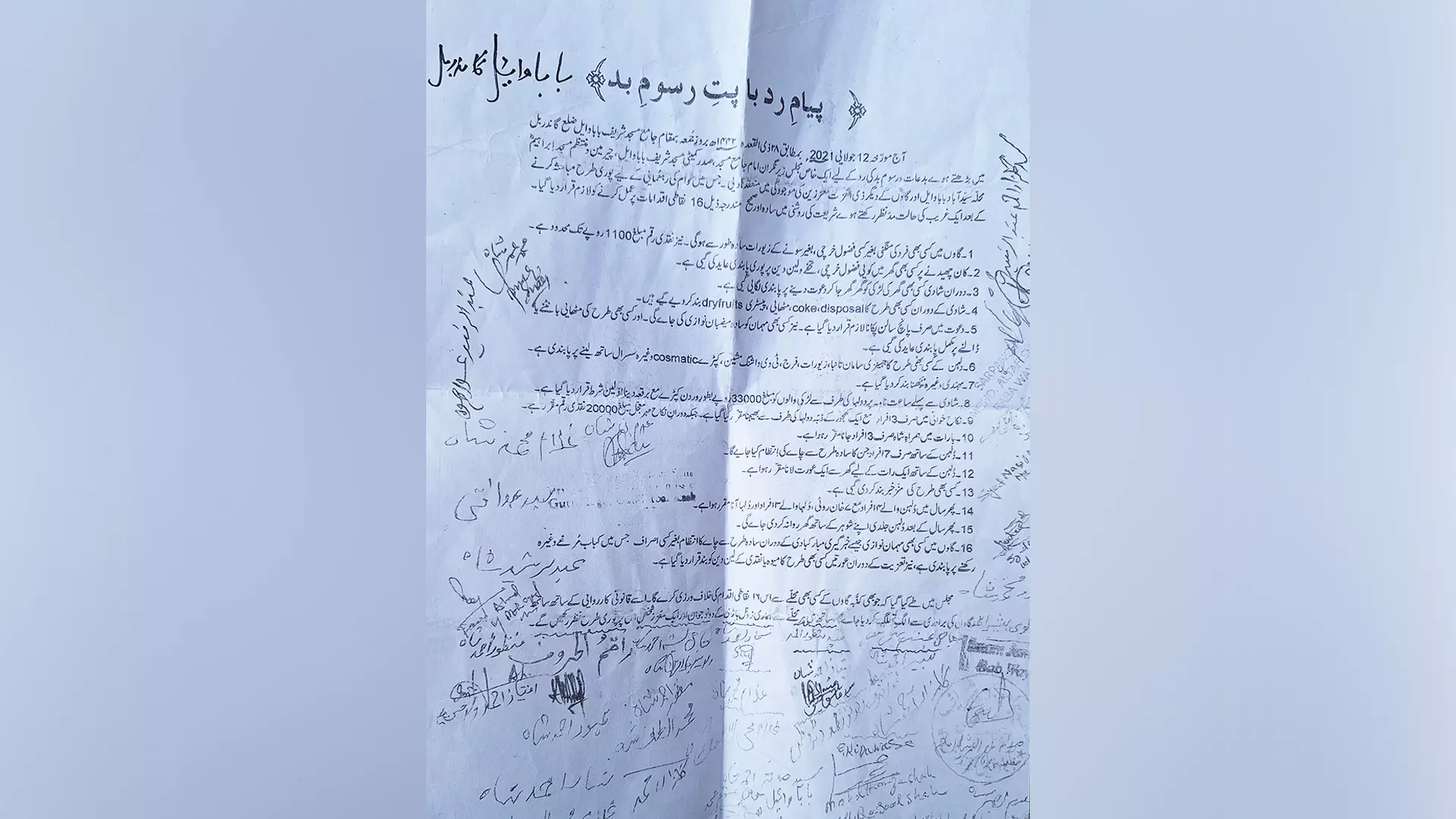

The practice of conducting simple marriages has been a longstanding tradition, officially drafted in 2004 when the village leaders decided to impose a complete ban on dowry and extravagant customs. The decision was the villagers’ way of introducing sanity among their people at a time dowry-related issues began to increase in the Valley. Concerned for the well-being of the children, the villagers drafted a document which outlined guidelines for weddings, endorsed by over 100 members of the community.

Since then young men and women of the village have been prioritising modest weddings over extravagant celebrations. Most wedding expenses are covered entirely by the groom’s family. A commitment to abstain from both giving and receiving dowry was formalised through the signing of a document in 2004. The catalyst for the agreement was the rising incidents of domestic violence over dowry demands within the village. These incidents prompted village elders, including the imam, to collectively draft and endorse the no-dowry document.

In 2021, 80-year-old Gulab Nabi Shah, Aawqaf president of Baba Wayil, convened a meeting with the imam, mosque committee members, and other locals to amend the document and obtain written agreements for regulating village weddings.

“The document amended in 2021 consists of 16 points with comprehensive guidelines for weddings to make the union simpler and set an example for the world. We have recommended the entire village to include only four to five wazwan recipes in marriage functions. In the past, a group of 10-20 people accompanied the groom to the bride’s house, but now only three to four persons are recommended,” Gulab Nabi said.

There are no exceptions to the rules set by the village.

A few months ago, a family in the area broke the custom by arranging an extravagant engagement ceremony for their daughter.

“Although we maintain peace and harmony in the village, the village committee members intend to take action against them because the head of the household had also signed the petition,” Gulab Nabi said, adding that they want to keep the identity of the family anonymous for now.

In the past, when a family accepted dowry and exceeded the expenses, they were ostracised by the village.

“To reduce the number of cases involving dowries, we will work to preserve this custom and try to spread it to other towns and areas,” he said.

The original agreement stipulated a payment of Rs 900 as mehr (a contractual amount to be paid by the husband to his wife in the event of divorce or death). The groom’s family was also supposed to give Rs 15,000 for marriage preparations, including 40 kilograms of meat and 50 kilograms of rice to the bride’s family. However, the amended document requires the groom’s family to pay a total of Rs 53,000, with Rs 20,000 allocated for mehr and the remainder for other expenses. No gold can be exchanged. Any deviation from these rules could result in stringent action by the village leaders, given that they have collectively endorsed the official document.

“At the time of the first visit of the groom’s family to the bride’s house (Thap Trawin), only one woman visits from the former’s side. Then both families jointly decide the details of the engagement (nisheen), with three to four representatives from each side being invited,” Shah said.

The document with guidelines for weddings in Baba Wayil.

Most men of the village have been following the custom happily and some said no to dowry even when the ‘rule book’ did not exist.

“When I got married, I took on the responsibility of covering all the expenses, including the bridal attire for my then would-be wife. There was no financial burden placed on the bride's family. I managed the entire affair with an expenditure of only Rs 15,000, which covered clothing, perfumes, shoes, and a pair of sandals. The overall cost of my wedding amounted to approximately Rs 60,000-Rs 65,000 rupees,” said Syed Mukhtar Ahmad, a villager who got married in 1990.

“Those who accept dowry or indulge in extravagant wedding expenses are not considered as part of the village. None of us in the village have contested the document, either in part or wholly,” he said.

What dowry did to Kashmir’s women

As the problem of dowry rose in Kashmir, many women were forced to remain unmarried as their families could not manage the wedding expenses. As per a recent survey of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Jammu and Kashmir has the highest rate of young people who are not married, with dowries being one of the causes for the trend.

The ‘Youth in India 2022’ study shows that 29.1% of young people (up to 29 years old) in Jammu and Kashmir are single, against the national average of 23%. In Kashmir, the number has steadily climbed from 18% in 2011 to 29.1 in 2022%.

Another survey conducted by Tehreek e Fala-Ul-Muslimeen, a non-governmental organization, revealed that the high dowry demands connected with marriage remain the primary cause of the approximately 50,000 women who were single at the age of 40.

Most people in Baba Wayil trade in walnuts or shawls.

According to data produced by the Crime Branch of the Jammu and Kashmir Police which was published in the Kashmir Monitor, 16 married women were killed in 2021 as a result of dowry demands made by their in-laws. Nine such cases had been brought before the crime section in 2020. The primary cause of the abuse committed by husbands in Jammu and Kashmir is the dowry.

“Hundreds of sisters remain unmarried because of dowry and the high cost of weddings which the women’s side in compelled to bear. Instead of seeking change from others, we should focus on changing ourselves first. It’s important to discourage marriages that compel families to incur debts and encourage simple unions throughout the Valley,” Ubaid Ah Shah, a graduation student from Baba Wayil, said.

“The introduction of the anti-dowry rule has resulted in zero instances of domestic violence, suicide, or conflicts among the bride/groom and their in-laws in our village. We are shocked and distressed when we hear reports of women being subjected to violence or taking their own lives in other parts of Kashmir, or other parts of India,” Ubaid told The Federal.

The idea of a dowry-free alliance or controlled expenditure on weddings goes beyond just saving money.

“The alarming surge in dowry cases reflects a deeply problematic gender injustice. It casts shadows on the autonomy and well-being of women. It leads to families seeing daughters as a burden because parents worry for their dowry. The evil also exposes the frailty of a system that commodifies the sacred institution of marriage,” said sociologist, Aadil Ahmed.

The impact of dowry harassment can be multi-fold.

“Such harassment becomes a cause of physical ailments, despondency, and anxiety among young girls, confining them to a life at home, dampening their spirits, suppressing their emotions, and creating challenges or barriers for them that stop them from realising their true potential,” Aadil said.