- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Arab women writers approach identity, memory, and power in fiction

“That country is gone now, it is finished, toppled over and shattered like a huge glass vase, leaving only shards scattered across the ground. To attempt to bring any of this back would end only in tragedy. It could produce only a pure, unadulterated grief, an unbearable bitterness,” observes an unnamed woman in Lebanese novelist Hoda Barakat’s novel Voices of the Lost (2020),...

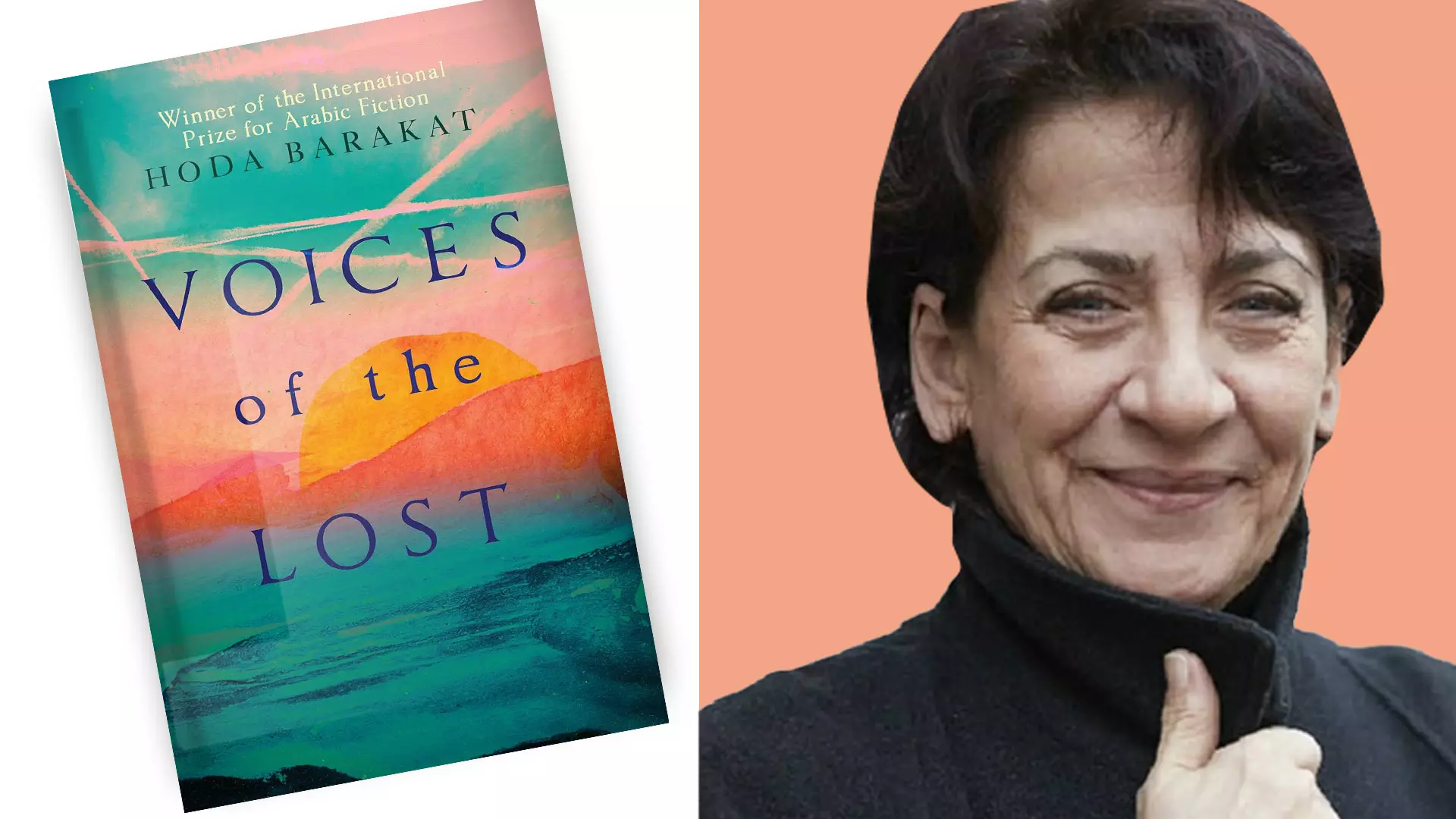

“That country is gone now, it is finished, toppled over and shattered like a huge glass vase, leaving only shards scattered across the ground. To attempt to bring any of this back would end only in tragedy. It could produce only a pure, unadulterated grief, an unbearable bitterness,” observes an unnamed woman in Lebanese novelist Hoda Barakat’s novel Voices of the Lost (2020), translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth, which won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2019. Set in an unnamed war-torn Arab country, the novel — a haunting exploration of exile, memory, and loss, all told through a chain of letters written by people on the margins of a fractured society — tells the stories of strangers who are bonded through their letters, which express yearning, guilt, and unspeakable traumas associated with migration.

Hoda Barakat’s novel 'Voices of the Lost' won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2019.

Paris-based Barakat (72) spent most of her early life in Beirut and has published six novels, two plays, a book of short stories, and a book of memoirs. Her works are centred on trauma and war. Her early three novels, set during the Lebanese civil war, are narrated by male characters living on the margins. They include The Stone of Laughter (1990) — the first book by an Arab author to have a main character who is homosexual — The Tiller of Waters (2001) and Disciples of Passion (2005). Barakat often explores themes of displacement and the fragility of selfhood. In her novels, exile isn’t merely a physical separation; it’s a psychic rupture, an unending tension between the desire to remember and the need to forget. Voices of the Lost captures this disorientation through a series of disembodied letters — lost voices searching for an audience, yearning for connection but written as if in the void. In the novel, language itself becomes a sanctuary and a weapon, a way to confront the instability of home.

Barakat’s prose is sparse yet haunting, as if her words, too, are in exile. In her stories, Lebanon is an elusive concept — neither refuge nor antagonist but a fluid space of memory and imagination, an ache that never fades. Her works challenge readers to confront their own preconceptions of home, identity, and the impossibility of resolution. Her characters do not find peace; they wander, their lives a patchwork of secrets and silences, hinting at the unspoken trauma that hangs over so many exiles. Barakat’s vision of the Arab world is of movement, of displacement as a permanent state, where home becomes a question that can never be fully answered. Barakat is only one among scores of women writers in the Arab world who are stretching the boundaries of storytelling. They are rewriting what it means to be a woman, a storyteller, and, in many cases, an exile. Through stories that refuse to settle into tidy resolutions, they invite readers into spaces of defiance, intimacy, and deeply felt contradictions. These are stories of survival, of inheritance and rebellion, stories that do not just ask to be read but demand to be heard, felt, and reckoned with.

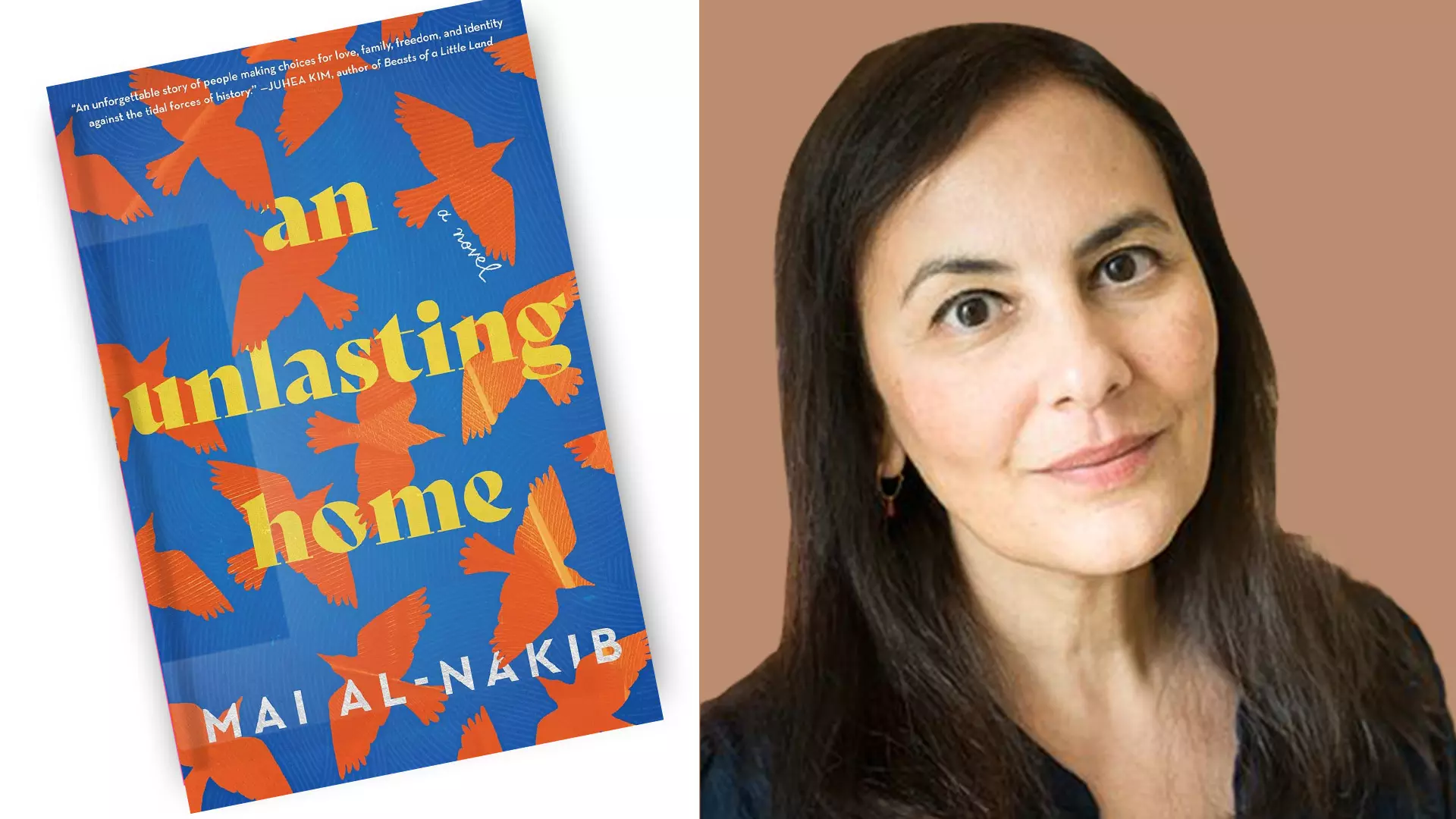

If there’s an Arab answer to Gabriel García Márquez’s family sagas, it’s Kuwaiti writer Mai Al-Nakib’s An Unlasting Home (2022), a novel that traces the lives of three generations in Kuwait with a finely tuned sense of historical urgency. Al-Nakib dives into the personal and the political with a deftness that feels both immediate and universal. Her characters walk a tightrope between tradition and the demands of a modern, globalised world — a world that expects them to move forward while keeping their roots firmly planted. In An Unlasting Home, which chronicles Kuwait’s rise ‘from a pearl-diving backwater to its reign as a thriving cosmopolitan city to the aftermath of the Iraqi invasion,’ Kuwait itself becomes a character, symbolising both opportunity and restriction. Al-Nakib captures the voices of women across generations as they grapple with questions of freedom and loyalty to heritage. What does it mean to progress while staying rooted? Al-Nakib’s novel wrestles with this question. According to a review in Los Angeles Review of Books, it’s “so fresh and unsettling that it will enchant you from the first page and linger for days after reading...Its epic family saga style echoes that of Hala Alyan’s Salt Houses and The Arsonists’ City, Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies, and Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko.”

Mai Al-Nakib’s 'An Unlasting Home' traces the lives of three generations in Kuwait with a finely tuned sense of historical urgency.

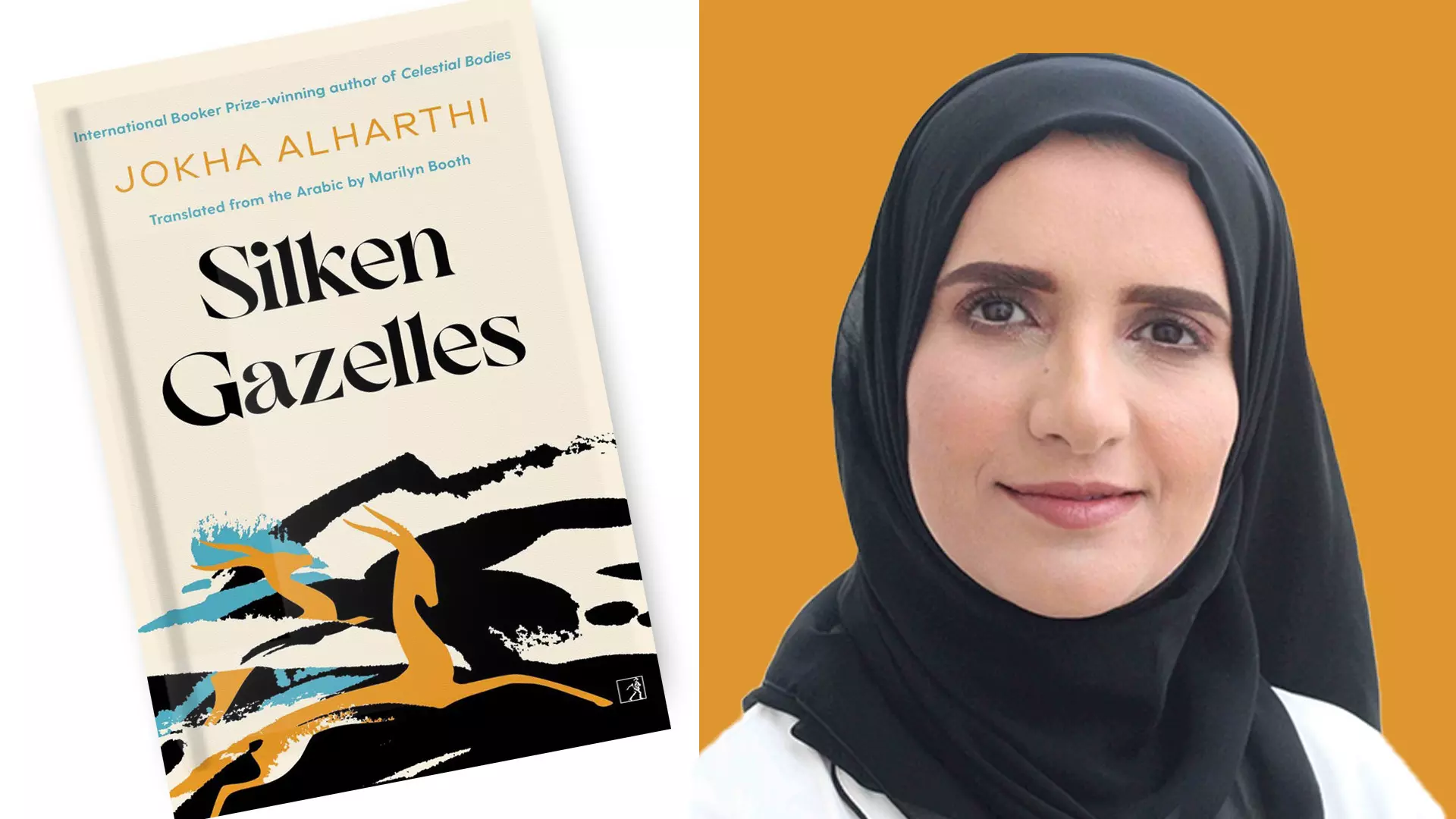

Omani writer Jokha Alharthi (46), who won the Booker International Prize in 2019 for her novel Sayyidat al-Qamar, published in English as Celestial Bodies, has come out with a new novel, Silken Gazelles. Translated from Arabic by Marilyn Booth, it has recently been published by Simon & Schuster India. It revolves around Ghazaala and Asiya, two women bound by a sisterly bond formed in early childhood. Raised together in a remote Omani village, their relationship is marked by profound attachment and kinship; it’s as powerful as that of birth siblings. But when Asiya is forced to leave, Ghazaala is shattered, haunted by this separation as she navigates her teenage and adult years. Moving to Muscat with her family, Ghazaala falls for a charismatic violinist and, defying her parents, runs away to marry him. She slips into her new role as a wife and mother, while also pursuing an education — all the while feeling the inescapable shadow of her lost friend.

The novel’s scope widens as Ghazaala’s friendship with Harir, a university classmate, takes on new dimensions, deepening over a decade into a connection that holds an unspoken resonance with her bond with Asiya. Through Harir’s diary, we witness her own transformative journey and her evolving friendship with Ghazaala, both women unknowingly tethered by the memory of Asiya. Alharthi illuminates how early bonds can echo across lifetimes, shaping relationships in surprising ways. Silken Gazelles also explores the paradox of absence — how a person no longer present can remain an undeniable force, silently shaping love, friendship, and identity. Alharthi’s prose conveys the emotional complexity of Ghazaala and Harir’s friendship, offering readers a richly layered meditation on loss, memory, and the multifaceted nature of female companionship.

Jokha Alharthi's 'Silken Gazelles' explores the paradox of absence — how a person no longer present can remain an undeniable force, silently shaping love, friendship, and identity.

Saudi writer Fatima Abdulhamid (42) enters the scene with an unapologetic boldness, portraying the lives of Saudi women with a frankness that defies the guarded norms of her homeland. Her novels, like The Farthest Horizon, tackle gender dynamics with a sharp, introspective gaze. Abdulhamid’s characters are not passive bystanders but fierce, intelligent protagonists who question their roles and push against the edges of their world. In her stories, there’s an undercurrent of unease, an awareness of how power and vulnerability intertwine in complex ways. Similarly, Syrian-Kurdish Maha Hassan’s Maqam Al-Kurd is a tribute to Kurdish identity that gives us a glimpse into a world shaped by dual struggles — ethnic and gendered marginalisation. Hassan gives voice to the Kurdish experience in Syria, a voice that has long been stifled in Arabic literature.

Iraqi-Danish writer Duna Ghali (61) uses her diasporic vantage point to tell stories that portray the fragmentation and displacement experienced by exiles. Her novels South and Orbits of Loneliness explore the terrain of nostalgia, belonging, and the wounds that come from living between worlds. Ghali’s characters are besieged by memories of a home that may no longer exist, a longing that becomes both a source of solace and an unending ache. Her prose is atmospheric, like a half-remembered dream, a mixture of memory and imagination that reflects the unsettled lives of her characters. Ghali’s fiction does not seek to provide closure but instead explores the open-ended nature of exile. Her characters live in the liminal space between past and present, grappling with a homesickness that transcends the physical. Ghali’s work delineates the complexity of the immigrant experience, the way in which identity, like memory, is never fully fixed but always shifting, always becoming. Together, these women writers are not just documenting their worlds but reimagining them, creating literature that demands to be read, felt, and reckoned with for its courage, beauty, and unrelenting pursuit of truth.