- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How a new initiative revisits history to help children make sense of their chaotic present

In a recent book, part of a series on partition titled Itihashe Hatekhori (First History Lessons), Anwesha Sengupta recalls the predicament of Joymoni, a government-owned elephant which found itself caught in a tussle between the two nascent nations.It so happened that during the division of government assets, Joymoni was allotted to East Pakistan. But its mahout (handler) refused to cross...

In a recent book, part of a series on partition titled Itihashe Hatekhori (First History Lessons), Anwesha Sengupta recalls the predicament of Joymoni, a government-owned elephant which found itself caught in a tussle between the two nascent nations.

It so happened that during the division of government assets, Joymoni was allotted to East Pakistan. But its mahout (handler) refused to cross the border to take the pachyderm to Muslim-dominated East Pakistan, carved out of undivided Bengal. Ten months passed in bureaucratic wrangling over Joymoni’s travel plan. Finally, Pakistan decided that it would send two forest officials to fetch the jumbo.

As planned, two Pakistan officials arrived in West Bengal’s Malda where the elephant was stationed.

The history telling initiative is attempting make the subject fun for children.

“The District Collector told them that they would have to deposit Rs 1,900 before Joymoni could be taken away. On paper, he had been East Pakistan’s property since 15 August 1947, but the West Bengal government had paid for his food for the last ten months. And feeding an elephant was no small matter… Rs 19,000 was a significant sum of money back then. Those who had come to fetch Joymoni did not have so much money with them. But the collector was adamant: he wasn’t going to let Joymoni go without the dues being paid,” thus the story goes.

Joymoni’s story alluded to constant bickering between India and Pakistan over “many small and large issues” after partition.

“Even today, we only have to open the newspaper to read of the conflict between the two countries over Kashmir. Is the partition only a historical event, then, or is it still underway?” the author goes on to ask the children.

The series is full of such narratives weaved in to explain contested issues and complicated narratives in simple words and playful photographs and illustrations.

The work is a result of a Kolkata-based research institute — Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata (IDSK) — joining hands with a transnational alternative policy lobby group — Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung (RLS) — centered in Germany to revisit the craft of history-writing for children to purge the subject of political influence by helping discern facts from fictions.

The picture books narrate sensitive historical events and issues such as partition of Bengal, infiltrations from across the border and National Register of Citizens in a language intelligible to children.

“The initiative aims to challenge existing perceptions of the past by innovatively re-exploring the histories of everyday sites, commodities, and events,” read a concept note of the project.

“In India, children's understanding of the past is often influenced by societal, communal, and national stories, notions, and symbols that they are taught to regard as inviolable. As a result, their perception of history is frequently shaped by patriarchal, majoritarian, and statist values,” it pointed out.

The project is being liked by children.

“The book on partition helped me to see the event from a new perspective. I could relate it with my family’s history since my grandfather had migrated from what was then East Bengal. The way the event was narrated evoked a keen interest in me to know more about it, and I pestered my grandfather to narrate his tales of partition to me,” said Roopkatha, a Class 8 student of Patha Bhavan, Kolkata.

The project was much needed in today’s India.

Contemporising history

Indian history has never been as contemporary as it is now. Our current political narratives and even social discourses are shaped by historical events and personalities perceived irrelevant long ago.

Take the case of a certain Gopal Chandra Mukherjee, popularly known as Gopal Pantha. A male goat is called ‘pantha’ in Bengali. Mukherjee used to run his family mutton shop on Kolkata’s College Street, and hence the sobriquet, which is often used pejoratively for a dull-witted person.

Over a decade after his death in 2005, Mukherjee, whom his contemporaries dubbed pantha, has emerged in the socio-political scene of Bengal as a polarising figure for what he did before the partition of the province 78 years ago. For some, he is a hero of Kolkata, a rakhakarta (saviour) of the city. Many others think he was a headstrong hoodlum. The opinion varies depending on the political prism through which he is being viewed.

This lesser-known character in Bengal’s modern history was first resurrected in popular memory when an equally lesser known far-right group Hindu Samhati celebrated his birth centenary feting him as ‘Kolkatar Rakhakarta’ and a Hindu bir in 2014. Since then, Hindu groups have not let go of any opportunity to ensure that Mukherjee does not pale into oblivion again.

His legacy has become important for the right-wingers for his role in the brutal communal riots in Kolkata (then Calcutta) sparked by the Muslim League's call for Direct Action on August 16, 1946.

Mukherjee is not the only historical figure around whom political narratives are currently being woven to mould people’s perception about both past and the present happenings.

Rajasthan education minister Madan Dilawar last week scripted his own version of Mughal history calling emperor Akbar “a rapist”.

Allegations are even galore about history textbooks for students being rewritten to promote certain political narratives.

Making sense of history

Against this background, IDSK, with funding from RLS initiated the project to write history for children in 2022.

Three women historians were assigned the task to create a series of illustrated history books for children aged between 12 and 14 years to make the subject absorbing and fascinating for children and more importantly to put it into right perspective.

The trio Anwesha Sengupta, Debarati Bagchi and Tista Das penned three books in 2022 as part of the series christened Itihashe Hatekhori that is First History Lessons in English.

Two more academics Santanu Sengupta and Suparna Banerjee joined the team in 2023 to bring out three more books as part of the series.

The focus of the three-part series published last year was war, environment, and commodity histories. The themes in 2022 were border, migration, meanings of India/Indian and linguistic diversity.

The picture books narrate sensitive historical events and issues such as partition of Bengal, infiltrations from across the border and National Register of Citizens in a language intelligible to children.

Interesting anecdotes, such as that of Joymoni, sprinkled amidst serious topics like territorial disputes, concept of war, citizenship rights, water-sharing make the series more compelling.

“With this (Partition) series, we are trying to encourage children to engage with India’s history beyond the school-mandated textbooks so that they can understand a nation, its identity and boundary are all historically constructed ideas and not sacrosanct principles,” explained project coordinator and series editor Sengupta, who is also an assistant professor with the IDSK.

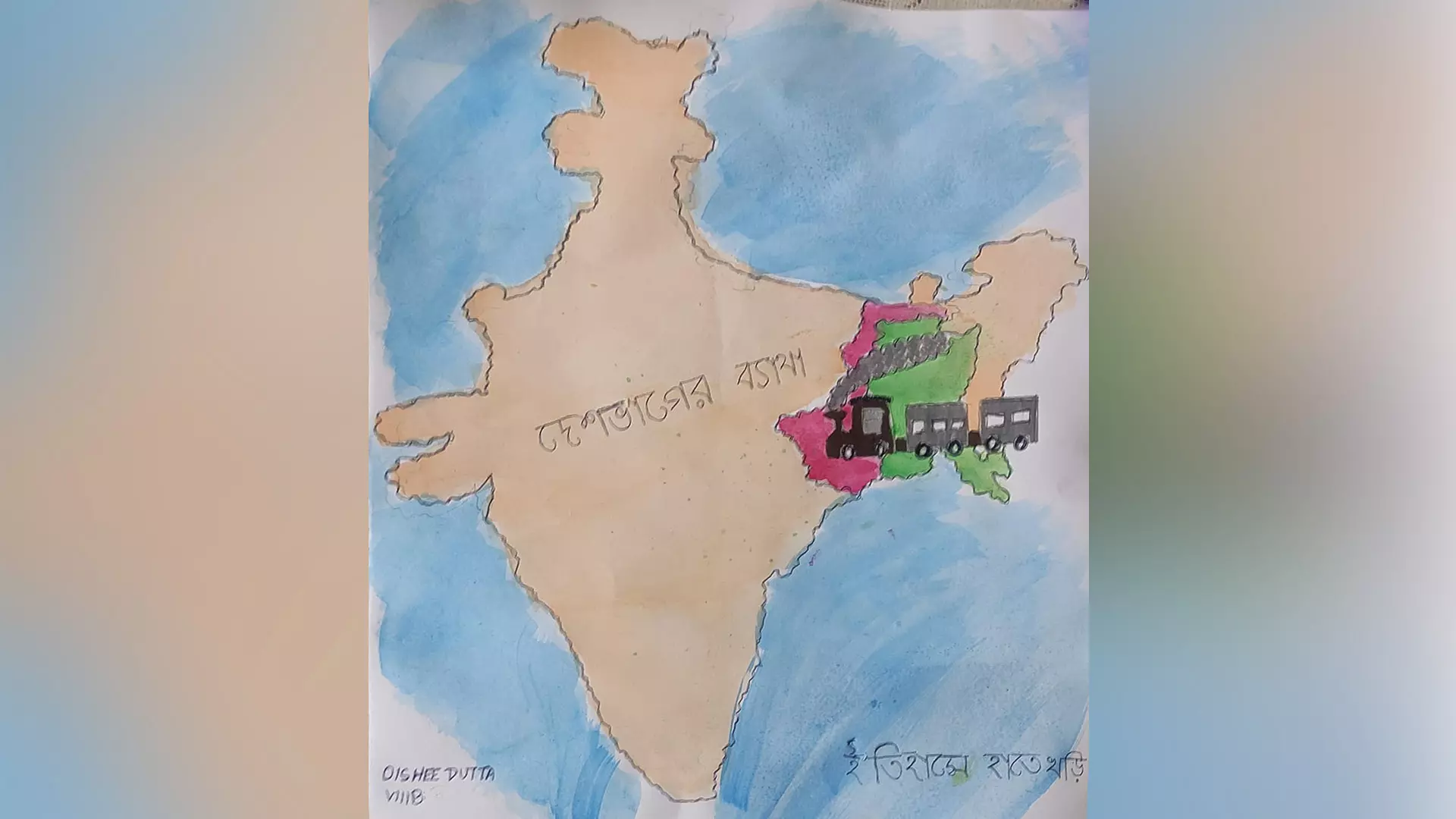

A drawing by Oishee Dutta, a class VIII student, after reading the book on partition.

Another prime objective of the project is to drill into children the importance of authenticity of sources in a historical account so that they do not get influenced by fake or distorted narratives so often peddled in social media, she said.

In the concluding chapter in the book Partition, Sengupta addresses the elephant in the room.

“You may be wondering how I got to know all these stories. What if I made them all up?” the chapter prods.

It then goes on to disclose how the author read about Joymoni the elephant in Bangladesh government’s archives to the extent of even divulging file numbers.

Writing history scientifically

Chapters on sourcing is an integral part of the series.

Copies of the books are distributed free of cost to schools, NGOs, students and teachers among others while the PDF and open-source versions are freely available on the IDSK websites. The e-version is also circulated through social media. These apart, the IDSK organises workshops among the children and collects their responses.

The future of Indian history now rests much with children, their objective engagement with the past.