- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

In a four-bedroom house in Ilford in East London, 30-year-old Agini wakes up at 4 am. There is no time for her to laze around. She quickly dresses up and gets ready for the two-hour bus commute to a nursing home in South Norwood, where she works from 8 am to 8 pm as a healthcare assistant (HCA) for geriatric patients. Agini reaches back home by 10.30 pm. There is no time to unwind. She takes...

In a four-bedroom house in Ilford in East London, 30-year-old Agini wakes up at 4 am. There is no time for her to laze around. She quickly dresses up and gets ready for the two-hour bus commute to a nursing home in South Norwood, where she works from 8 am to 8 pm as a healthcare assistant (HCA) for geriatric patients. Agini reaches back home by 10.30 pm. There is no time to unwind. She takes a bath, heats up dinner, takes quick large bites to hit the bed immediately.

In this mundane life in a cold country, the only relief for Agini is that she is not alone. Staying with her are 46-year-old Nissy from Wayanad, 44-year-old Ambika from Trichur and Preethi, who is the same age, from Ernakulam.

All four women hail from Kerala and work as healthcare assistants in London. While they work as healthcare assistants, they are not nurses. All four are commerce and art graduates from regular middle-class families, who were married off at a young age, and remained housewives. Apart from occasional money crunch, all had led a life free of stress, until they decided to leave Kerala for an overseas job.

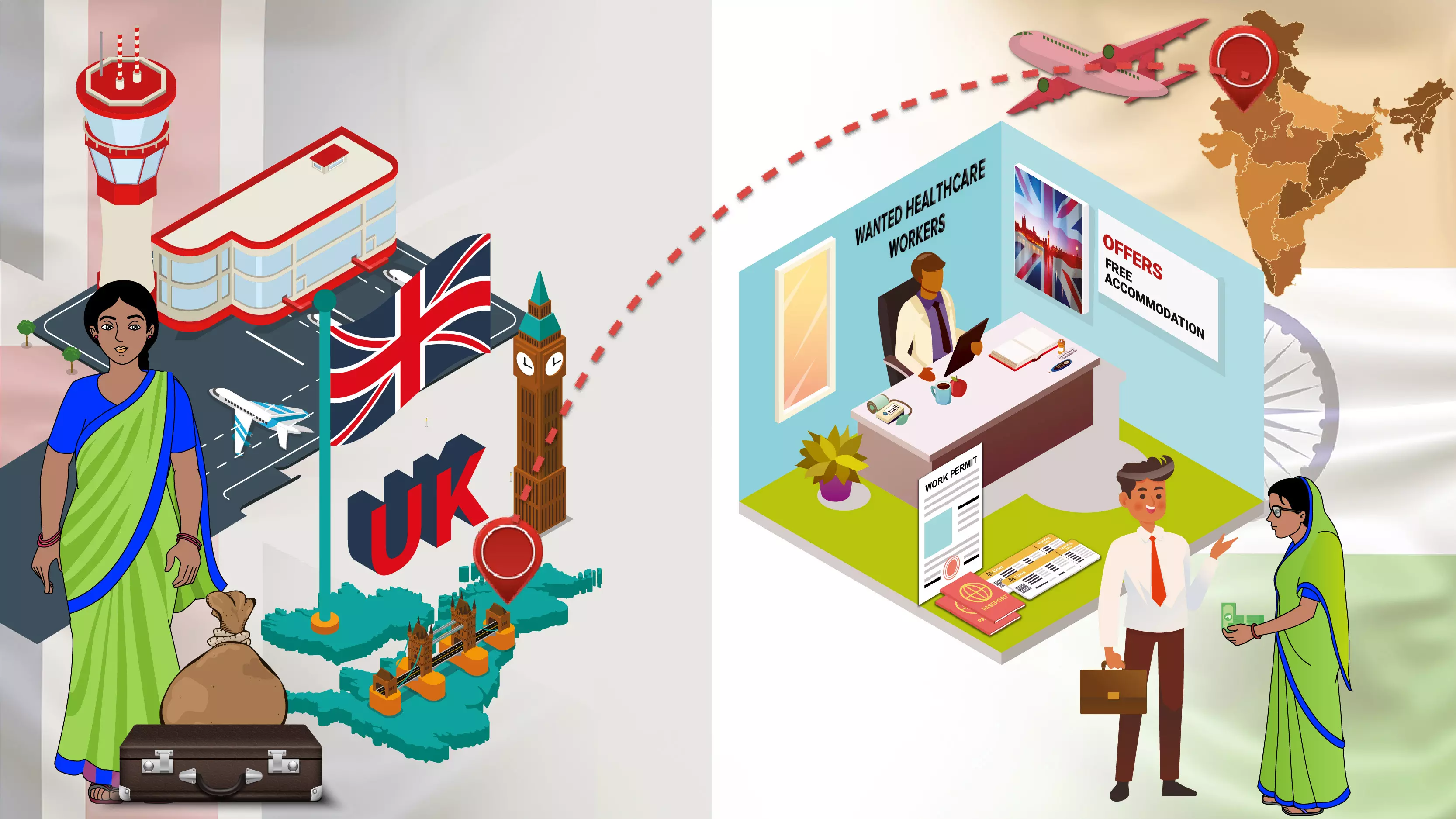

To pursue their dreams of working abroad, the women met an agent, reportedly from the largest recruitment agency in Ernakulam, which promised a new life in the UK. They landed in London on a domiciliary care visa.

“I heard about this agency through a friend. In June 2022, my husband and I went to their office and they explained what a domiciliary care visa is. They told us it means we can get work in any nursing home without being a nurse. All that was needed was for us to be physically and mentally fit to care for the elderly. We paid Rs 1 lakh in cash. They said there’ll be a telephonic interview by a recruitment agency for health services called Redspot in the UK,” Agini told The Federal.

“Somebody with a British accent did call. I can’t recall what he asked. For months, there was no progress. We used to keep calling and they’d say the processing takes time. Finally, in May 2023, I appeared for a video interview with a panel of four Afro-American men. They asked me if I had any experience in caring for the elderly. By then, I had completed a one-month online course on caregiving, suggested by the agency, and also completed an internship with a local nursing home to obtain a work experience certificate. Immediately after that interview, we were asked to come to the office and pay Rs 4 lakh. They said the money was for Redspot, which will confirm the job after getting the money. One week before leaving India, I was asked to pay Rs 7 lakh more. They again said the money was will be given to Redspot for my COS (certificate of sponsorship), accommodation and tickets. The agency promised us that they would be paying the rent of the house for the two-year period of the domiciliary care visa, or refund the Rs 6 lakh on our return,” Agini added.

The agency insisted on cash payments each time.

Agini, Nissa, Ambika and Preethi reached Heathrow airport on July 22, 2023. What has unfolded since for the women has left them helpless and devastated in a foreign land.

“When we saw the accommodation provided for us, we were shocked. Around 16 women from various parts of India were already living in the three-bedroom house, we didn’t even have space to keep our luggage. We called the owner of the Ernakulam agency. Our families went to the office and raised a ruckus. Finally, I contacted a Malayali pastor in the UK who I knew from back home and after three horrifying days in that cooped-up facility, we moved to a four-bedroom house, with seven women, owned by a Malayali. The jobs we were promised did not materialise either. For a week, we spent the money that we had brought with us. Again, one of my church members from back home intervened, and Nissy and I were asked to report at the nursing home in Ilford,” said Agini.

According to the stipulations of the two-year domiciliary care visa, a care worker in the UK is expected to make house calls, and work for at least two hours a day. She does not have to be a qualified nurse, just be healthy enough to care for the geriatric — bathing, feeding, washing laundry, cleaning rooms, everything except giving medical care.

A domiciliary care worker cannot work for more than 20 hours a week.

Agini and Nimmy get paid 10.50 pounds (about Rs 1,000) per hour. Although they work for 12 hours straight, the pay slip can show only 11, the one missing hour being the time taken for normal breaks and lunch. Which means at the end of two days, they each get paid 231 pounds (about Rs 23,100). Naturally, the two-days-a-week work schedule is not enough.

The other days of the week, they are not legally permitted to work but some of them do take an extra shift at the same nursing home and get paid under the guise of travel allowance or overtime. Every penny that comes into their account is under scrutiny, and there can be no slip-ups.

“We walk half an hour to a Gurudwara here. We get free food, three times a day. We’ve registered in a food bank, which enables us to get one delivery a month of whatever groceries we need, free of cost. Our rent costs 350 pounds a month, our work commute is another 10 pounds a day, recharging the mobile costs 10 pounds a month, leaving us very little to tide by,” says Nissy.

Nissy’s problems seem to be stretching from the UK to Kerala.

Her husband had taken a loan of Rs 6 lakh against the title deed of their house. “He is paying interest from his own income because I haven’t been able to send a single penny home yet.”

The last two weeks, all four were jobless. “We are only called to work when there are extra shifts that their permanent staff cannot take on.”

Ambika had left her government clerical job back in Thrissur to pursue a life in the UK. “My neighbour gave me this flyer from the Ernakulam agency. It was a very enticing advertisement. All along I wanted a work visa, but getting that on a non-medical job would take years, they said, so very reluctantly, I arrived in the UK on a domiciliary visa.”

During her long wait, she had enrolled for a 180-hour online course in caregiving from the St Norbert College, Canada, in collaboration with the NSDC.

“I was ready to do any kind of care work, but within three days of reaching here, I realised we were victims of a huge hoax.”

Unlike Nissy and Agini, Ambika got very little work — around 10 shifts in four months. “My family had to send Rs 87, 000, just so that I can pay my rent and buy food. I cannot even think of returning empty-handed. The Rs 11 lakh paid to the agency was by pledging my gold and our property documents. I’ve not only been unsuccessful in sending money home, I’m still taking from them,” she says.

Preethi has had it worse — only five shifts in four months. She’s not able to get a new job because they ask for a work reference and the copy of her first payment slip. Both are impossible because her shifts have been with different nursing homes.

The women are not willing to sue the agency in Ernakulam yet. “We just want to complete the two years somehow and earn as much as we can. We are worried that if we file a case, they may contact the authorities here and get us deported. The temporary shifts we have worked so far in these nursing homes is because of the kindness of other Malayalis living here. How long will that last,” Preethi says with worry laced in her voice.

Their families back home are trying to get a refund of at least Rs 6 lakh, as was promised. All kinds of threats and accusations against the agency have fallen flat, because the women are willing to talk but are not brave enough to file a complaint. What is more, they had reportedly also signed an agreement and handed over a blank cheque.

Mohammed Shihab, general secretary of Indian Nurses Association, has submitted a complaint to Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan and state police chief Shaik Darvesh Saheb, stating that dubious recruitment agencies are fleecing young women and enabling human trafficking under the guise of getting them jobs in the healthcare sector, in Europe and the UK.

In his letter, Shihab states, “These agencies are growing in numbers. They tempt middle-class families by offering citizenship through nursing jobs. Most sell or pledge their properties to pay the exorbitant amounts demanded by these recruiters. After reaching their destination, they realise they’ve been duped but they are threatened so badly, it becomes impossible for them to protest.”

In response to Shihab’s registered complaint, the police called Agini in the UK to verify the allegations. She confirmed paying Rs 11 lakhs to the agency and also spoke about being cheated on various counts, but eventually, refused to testify. “The investigating officer told me he is helpless. Unless the victim testifies, there’s nothing anybody can do about it,” Shihab said.”

With no crackdown on such agencies, more women are falling in their net and travelling overseas. Because at the end of the day, it’s all about the pay. Agini makes approximately Rs 1 lakh after 10 shifts. She has done a total of 27 shifts. “That is almost three lakhs in four months. So, if she gets at least four shifts in one week, at 115.50 pounds per shift, she will make decent money,” he said.

“Their husbands can also join them on a dependent visa. Their children can get free education in schools,” Shihab said, adding all this on non-medical qualifications and the least amount of paperwork — it’s no wonder that fraudulent recruiters are mushrooming in Kerala by the second.

Agini and Nissa are moving into a new rental house this week. One more batch of women is arriving on domiciliary visa, and it’s impossible for all of them to stay there.

Two days back, Redspot called to say that they need to buy a car as soon as possible and begin domiciliary care visits to houses. “We will have to face the charges of doing illegal work in nursing homes if we do not start the home visits,” Nissa said.

“We are not going to buy anything at their behest. They’ve not complied with any of the promises that they made before we left India. We called the agency in Ernakulam and told them that if they coerce us anymore, we will give everything up, return home and sue them,” she added.

Even as the women count their days and eagerly wait for work, they wonder why and how they got stuck in the problem.

“If we were their own sisters or daughters, would they want us to live like this,” Ambika asked.