- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Heritage tourism breathes life into Chettinad's forgotten mansions

In the remote village of Kanadukathan, nestled in Tamil Nadu’s historic Chettinad region, bullock carts crunch against sun-baked earth, as morning air hangs heavy with jasmine, lotus and lilies; and locals gather outside their homes—bare chested men in lungis and women draped in sarees—some engaged in conversation, others simply resting in peaceful leisure. Also read | A terrifying...

In the remote village of Kanadukathan, nestled in Tamil Nadu’s historic Chettinad region, bullock carts crunch against sun-baked earth, as morning air hangs heavy with jasmine, lotus and lilies; and locals gather outside their homes—bare chested men in lungis and women draped in sarees—some engaged in conversation, others simply resting in peaceful leisure.

Also read | A terrifying descent into the dark web of misogyny, teenage rage

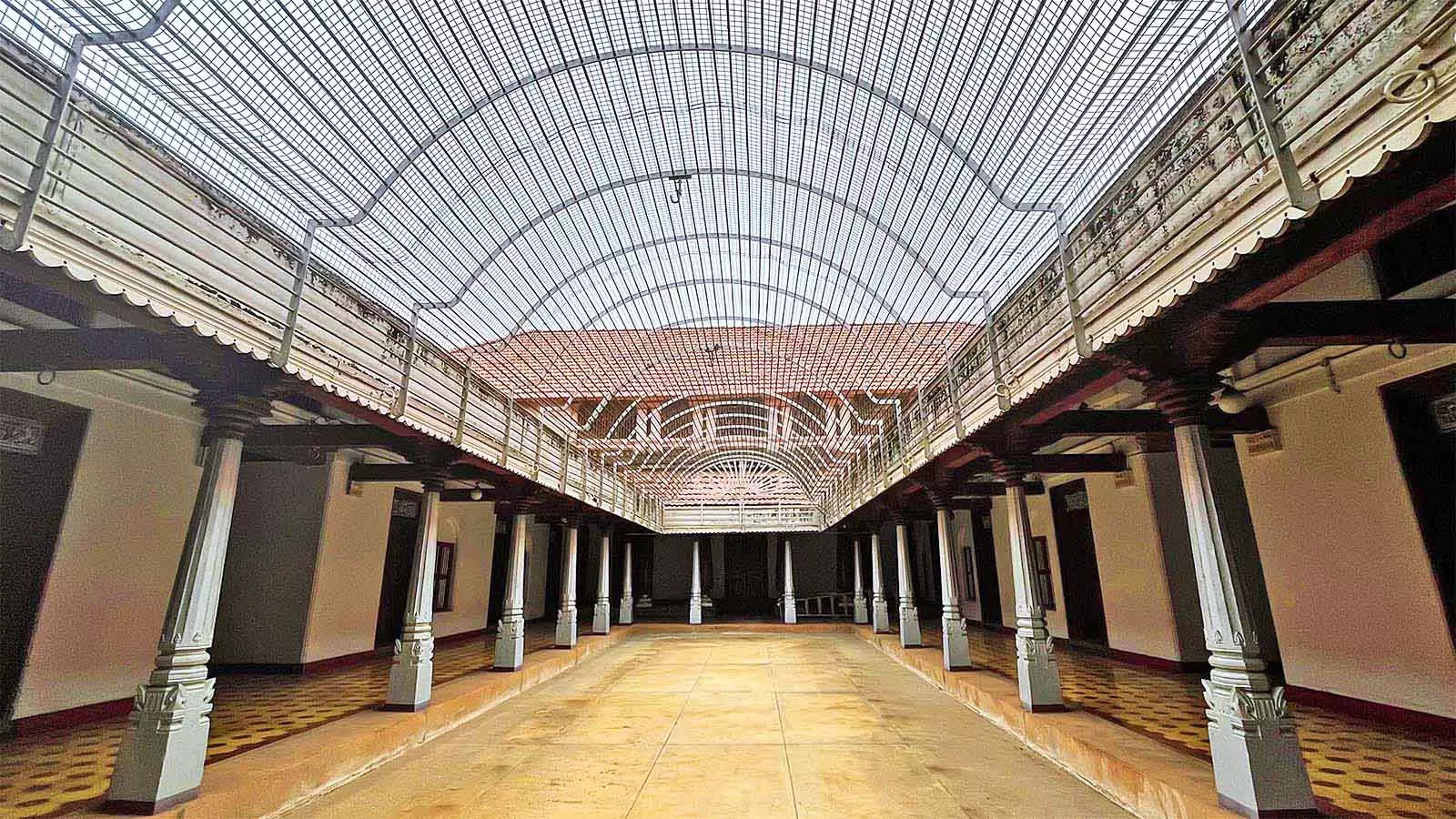

A trickle of visitors navigate labyrinthine lanes on foot, barely wide enough for a single cart, passing weather-worn mansions with imposing facades—Chettinad Palace, Erankovil Padappu Veedu, Chettinadu Mansion—stoic keepers of a prosperous merchant past. In about 30 minutes, the bullock cart arranged by Visalam, a Chettinad mansion constructed during World War II and transformed into a heritage hotel in 2007, halts at the Athangudi Palace, as the rhythmic clop of hooves echoes off century-old walls.

Visalam, a Chettinad mansion constructed during World War II and transformed into a heritage hotel in 2007.

Athangudi is one of the 96 villages that once formed this now-abandoned dominion, where nearly 10,500 opulent mansions loom like sleeping giants, their locked but colourful windows staring blindly into a present they never imagined. “Most of the mansions are crumbling due to neglect, abandoned by owners who have moved away,” says Shiva Shankar, manager and official guide appointed by Visalam. “Only a few, like this one, remain intact, thanks to dedicated maintenance by their owners. While they no longer reside here, caretakers have been assigned to live on-site, ensuring regular upkeep.” For those seeking a glimpse into Chettinad’s architectural grandeur, some of these historic homes are even available for rent. “In certain cases, some of the mansions can be leased for as little as ₹10,000 a month, with access to five or six rooms,” Shankar, his English fluent and precise, goes on.

Also read | The Persian technique that India made its own

A discreet exchange—a 50-rupee note pressed into a caretaker’s weathered palm—unlocks the massive wooden doors, their hinges groaning under centuries of history. Sunlight filters through Belgian glass windows, scattering prismatic patterns across Italian marble floors. In the open backyard, the blistering Tamil Nadu sun beats down on the crumbling façade, where time-worn pillars cast elongated shadows over the courtyard covered in Athangudi tiles. Yet, each step through the grand hallways feels less like a visit and more like an immersion—a walk into a living page of history itself.

Gesturing toward the towering Burmese teak pillars, Shankar delves into the history of the region’s illustrious merchant community. “The Chettiars, also known as Nagarathars, were a small sect of traders who originally hailed from Naganadu—now part of Andhra Pradesh. They dealt in precious stones, spices, and rice from Kanchipuram before migrating to Kaviri-Poompattinam, a port town on Tamil Nadu’s east coast,” he explains. Their trading empire flourished further during the Chola dynasty, expanding across East Asian markets.

Vairavanpatti Kovil in Karaikudi is a living relics of the region’s cultural splendour.

“In the 15th century, Pandya King Soundara Pandiyan invited the Chettiars to settle in his territory and boost economic activity. They established themselves in the villages allocated to them, spanning present-day Chettinad in Tamil Nadu,” Shankar adds, highlighting the deep-rooted legacy of this once-flourishing mercantile community. Athangudi Palace, also known as Sri Letchmi Vilas, carries a deep personal legacy. Named after Letchmi, the mother and daughter of its founder, Shri N. AR. Nachiappa Chettiar, the mansion's grandeur has earned it the title Periya Veedu—meaning Big House—and global recognition as Athangudi Palace.

Also read | What bone, marble and glass in Udaipur tell us about the forgotten inlay tales of Mewar

“In 1929, Nachiappa Chettiar, a prominent financier, constructed this vast 1.08-acre residence, employing a workforce of 150 artisans, many from Tirunelveli and Nagercoil,” explains Shankar. “Completed in 1932, the palace stands as a marvel of craftsmanship—built without modern electricity, cement, or tools, yet achieving an astonishing level of precision.” A crucial figure in the project was Chettiar's wife, who oversaw the construction with meticulous care. However, global events reshaped the family’s fortunes. “When war broke out, businesses shut down, and Nachiappa returned to his homeland.”

“There are nine clans and 96 villages—though now reduced to 75. In Kanadukathan alone, we have 99 mansions, but nearly 30% have crumbled over time, while the remaining 70% are still occupied,” says Shankar. While the region is renowned for its palatial homes, a few stand out as the finest examples of Chettinad grandeur. “The most distinguished among them are VVR House, AMA House, Chettinadu Mansion, Athangudi Palace, and MSMM House in Karaikudi,” he adds, highlighting the enduring legacy of these opulent residences, even as time takes its toll on others.

Muneeswarankoil Street's antique shops offer authentic antiquities from ancestral Chettiar mansions.

Beyond their opulent facades and intricate woodwork, the mansions of Chettinad stand as remarkable examples of green architecture and sustainable building techniques. From clay tile roofing to lime and eggshell plastering, these heritage homes were designed with climate-conscious principles long before sustainability became a global concern. One of the most striking elements of this eco-friendly craftsmanship is the use of Athangudi tiles, now synonymous with Chettinad’s architectural identity for over two centuries. A visit to tile factory on Athangudi Road in Sivaganga offers a firsthand glimpse into this centuries-old craft.

“Today, over 50 villages in Chettinad produce these tiles, each using Athangudi’s distinctive sand and water. Flecks of silica lend them their signature shine and smooth finish,” says RM Venkateshnan, owner of Loganayaki Ambal Tile Factory. “These tiles have witnessed shifting design trends, the rise and fall of empires, yet they remain a timeless symbol of elegance.” Interestingly, in the early 18th century, these tiles were not locally made but imported from Japan. However, the Chettiar merchants soon realized that installing them was a complex and demanding process. Determined to bring this craft closer to home, they began producing their own versions, adapting traditional techniques to local resources.

An antique shop on Muneeswarankoil Street.

In the early days, artisans infused colour into the tiles using silk cloth and natural vegetable dyes, as well as pigments derived from limestone. Over time, glass emerged as a preferred material for synthetic colouring, adding durability to the intricate designs. Muthugaman and his wife, Devi, who have been making these tiles for over 42 years, reveal the unique properties that set them apart. “The sand here is distinctive. Since we don’t have riverbed sand, we source it from the forests and surrounding areas. The high laterite content ensures that the tiles retain their luster even after years of use.” However, mining this sand in large quantities is restricted by government regulations, so masons transport it to factories in bullock carts.

The production process remains entirely manual, without large-scale machinery. “We can produce from 150 to 180 tiles a day using only a scooping spoon to pour the colours, a small shovel for the cement mortar, and a flat wooden plate to compress the mixture,” says Muthugaman. “From start to finish, the process can take up to a month.” Each tile is made to order, as prolonged storage can cause subtle discolouration, with the edges developing a different shade than the center. During the scorching summers, they keep floors cool. Because these tiles undergo continuous soaking and drying during production, they allow water to evaporate quickly, preventing dampness and structural damage—unlike other tiles that retain moisture and lead to mustiness.

Back at Visalam, a heritage mansion-turned-boutique-hotel, history is still carefully preserved in its sun-kissed yellow façade. “This is a Chettiar home featuring art deco architecture—the dominant style of the 1920s, marked by bold geometric designs and vibrant colours,” shares Sam John, General Manager of Visalam. Originally built by K.V.A.L.M. Ramanathan Chettiar as a wedding gift for his daughter Visalakhi during World War II, the mansion remained largely unused, serving only as a venue for family gatherings. Today, its grand halls have been transformed into guest rooms, maintaining their historic charm.

The mansion’s walls, finished with a unique egg-plastering technique, blend limestone, seashore shells, and black jaggery, polished to perfection with egg whites. The sprawling structure incorporates materials sourced from across the world—Italian marble for courtyard flooring, black marble pillars, a spiral staircase with iron girders from Birmingham, and Burmese teak wood that elevates the ceilings. But Visalam is not just about its architectural grandeur; it also upholds Chettinad’s culinary traditions through diverse dining experiences, from Sapadu Shala and the Terrace Grill to the Garden Café under a bougainvillea tree and the rustic Tea Kadai.

A renovated mansion.

“Chettinad cuisine is not only one of the spiciest in India but also among the most aromatic. The secret to its distinctive flavour lies in freshly ground spices, including star anise, which lends depth to every dish,” shares Executive Chef Tennyson Mathew. His words come to life through a sumptuous spread—sweet pongal, masala seeyam, vellai paniyaram, kalan karuveppilai, kadamba curry, crab curry, and Burmese rice, all served on a traditional banana leaf.

Since the start of 2022, the Chettinad Heritage and Cultural Festival has sparked a significant revival in Chettinad, not only helping arrest the decay of historic structures but has also reviving numerous intangible traditions, reigniting global interest in the region’s rich past. This cultural initiative was conceived by Meenakshi Meyyappan, a nonagenarian affectionately known as “Aachi”—the traditional designation for women of the region's Nagarathar community, whose male counterparts, are called “Chettiars.” The four-day September festival, now in its fourth year in 2025, generates approximately ₹2,045,341 daily for the local economy. Concurrent with this event, the number of certified local guides has tripled, from four to 12, while two historic mansions—Palaniappa Vilas and Lakshmi Vilas—have been fully restored.

“The aspiration behind the Chettinad Festival arises from the fact that we could not be bystanders and watch this rich heritage crumble. What was a crumbling depreciating asset needed a fresh injection of life. The region needed economic activity, industry or agriculture was not happening. The only way out was tourism. Tourism has been a game changer worldwide in many distressed economies. So we decided to showcase and create an event that could promote the region and put it on the tourist map,” says Yacob Thomas George, the festival’s coordinator, noting increasing attendance each year. The festival in its last three years has established a conceptual framework: architectural tours, cultural lectures, and performing arts—honouring tradition while fostering innovation.

One of the most striking elements of this eco-friendly craftsmanship is the use of Athangudi tiles.

“The festival has significantly enhanced appreciation for Chettinad’s unique history and craftsmanship,” says John. “It provides a vital platform for local artisans, chefs, and performers, fostering economic growth and positioning the region as a cultural destination.” At the heart of this initiative is Visalam, a prominent heritage property that plays a crucial role in supporting the festival. As a symbol of Chettinad’s architectural grandeur, Visalam not only hosts key events but also acts as a cultural ambassador, promoting local crafts, authentic culinary experiences, and meaningful engagement with visitors. "With 2025 marking the fourth edition of the festival, organizers are expected to introduce new initiatives focused on sustainability and eco-tourism. Expanding its programming, the festival may include more interactive cultural experiences, hands-on workshops, and collaborations with global heritage organizations, ensuring that Chettinad’s traditions continue to thrive and inspire future generations," he adds.

Beyond commerce, Chettinad's nine Chola-style clan temples—particularly the historically significant Pillaiyarpatti and Vairavanpatti Kovil in Karaikudi—remain as living relics of the region’s cultural splendour. The distinctive Ayyanar shrines with their imposing terracotta horse sentinels continue to embody protection and prosperity for locals and fascinate visitors. For those seeking tangible connections to this storied past, Muneeswarankoil Street's antique shops offer authentic antiquities from ancestral Chettiar mansions—allowing visitors to carry home not just souvenirs, but fragments of a cultural legacy that continues to thrive against the backdrop of present age.