- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

From rallies, to AI, to even deep fake, how Bengal is making a pitch for votes

The Election Commission of India (ECI) had to rope in young boys in many booths in the state to put indelible ink markers on the finger of female voters during the country’s first general elections in 1952.One such young volunteer was noted educationist Pabitra Sarkar. The arrangement was made to allay inhibitions among some female voters about their finger being touched by an adult,...

The Election Commission of India (ECI) had to rope in young boys in many booths in the state to put indelible ink markers on the finger of female voters during the country’s first general elections in 1952.

One such young volunteer was noted educationist Pabitra Sarkar.

The arrangement was made to allay inhibitions among some female voters about their finger being touched by an adult, recalled Sarkar, who was a 15-year-old volunteer then, in one of the booths in Kharagpur under Midnapore Lok Sabha constituency.

From there to theme-based model polling stations, the election process in the world’s largest democracy has been constantly evolving just as it did from ballot boxes to electronic voting machines.

Yellow roses were offered by polling officials to voters on arrival at Maharani Kashiswari Girls' High School polling station, decked up as a model polling centre at Murshidabad district’s Baharampur Lok Sabha constituency. Toys and toffees were given to children accompanying parents, sitting arrangements were made under tents and cold water was served.

Yellow roses were offered by polling officials to voters on arrival at Maharani Kashiswari Girls' High School polling station, decked up as a model polling centre at Murshidabad district’s Baharampur Lok Sabha constituency.

The entire premise that housed four polling booths was colourfully decked up with balloons and other decorative props.

EC officials said such model centres have been set up for the first time all over the state to enhance the voting experience.

“Voting here was a pleasant experience… It’s a very good initiative of the ECI,” said the constituency’s Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP) candidate Promathesh Mukherjee, also a voter at the polling station.

The transition is more visible in campaigning and election management by political parties and their candidates.

Running parallel to the conventional physical canvassing through roadshows, rallies, street-corner meetings, door-to-door outreaches, the parties took their campaign to cyberspace as never before. The use of artificial intelligence has taken digital campaigning to a different level.

Former Bengal chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee showed up on social media platforms of the CPI(M) on May 4 with his thinning grey hairline and trademark white kurta and dhoti.

“Remember, the BJP thrived in Bengal during the TMC regime. Who is Narendra Modi? Who is Mamata Banerjee? Do not let them destroy our state and the country,” he was heard appealing to the electorates in a 2.06-minute video.

He took on both the BJP government at the Centre and the Trinamool in the state dwelling on issues ranging from alleged sexual harassment of women by TMC functionaries to corruption through electoral bonds.

The ailing former chief minister made the last public appearance for electioneering in February 2019. Since then, his health has kept him away from campaigning, though his presence, the party leaders feel, could have bolstered the Left Front’s electoral prospects. More so at a time when it has made lack of industrialisation, growing unemployment, corruption and communalisation its main poll planks.

The party tried to make up for his absence by ‘recreating’ him using artificial intelligence. The audio and the video were AI-generated, the party declared.

The CPI(M) is also using an AI-generated anchor, Samata, for their campaign on social media, a giant leap towards the change for the party that had in the 1970s opposed introduction of computers in banking and insurance sectors.

The CPI(M) is using an AI-generated anchor, Samata, for their campaign on social media.

The CPI(M) though is the first party to use AI for campaigning in Bengal, producing cloned avatars and even resurrecting dead leaders to give an edge to the campaigning has become a new outreach tool.

Animated videos and synthetic contents developed with the help of technologies are widely used by parties cutting across party lines to dominate cyber space.

Not surprising then that the viral digital contents are getting prominence increasingly. One of the raging debates in this election in Bengal is over the authenticity of a sting video.

In the video, a BJP booth president in Sandeshkhali Gangadhar Kayl was heard saying that the allegations of sexual harassment of women there by TMC leaders were concocted at the behest of leader of the opposition in the West Bengal assembly Suvendu Adhikari.

The local BJP functionary was further heard saying in the unverified video that guns were planted at a house in Sandeshkhali and were later shown as the seizure by central agencies.

Releasing the video, the TMC accused Adhikari of creating false narratives to defame Bengal.

Kayl claimed in a written complaint to the CBI that the video was a deep fake and his voice was modulated using AI to mislead people.

Another video that went viral was of Congress leader Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury. In the video, he was purportedly telling electorates that it’s better to vote for the BJP than the TMC. It was later learnt that the video was fake.

Good or bad; real or fake, the state has never seen such digitalisation of elections.

A sneak peek into TMC leader Mahua Moitra’s main campaign office at a two-storeyed building in Krishnanagar typified the digital transition.

The two ground-floor rooms resembled a call centre. A team of researchers from Indian School of Democracy was handling her digital campaign. One of the key features of her outreach drive was direct interactions with voters through an AI chat box.

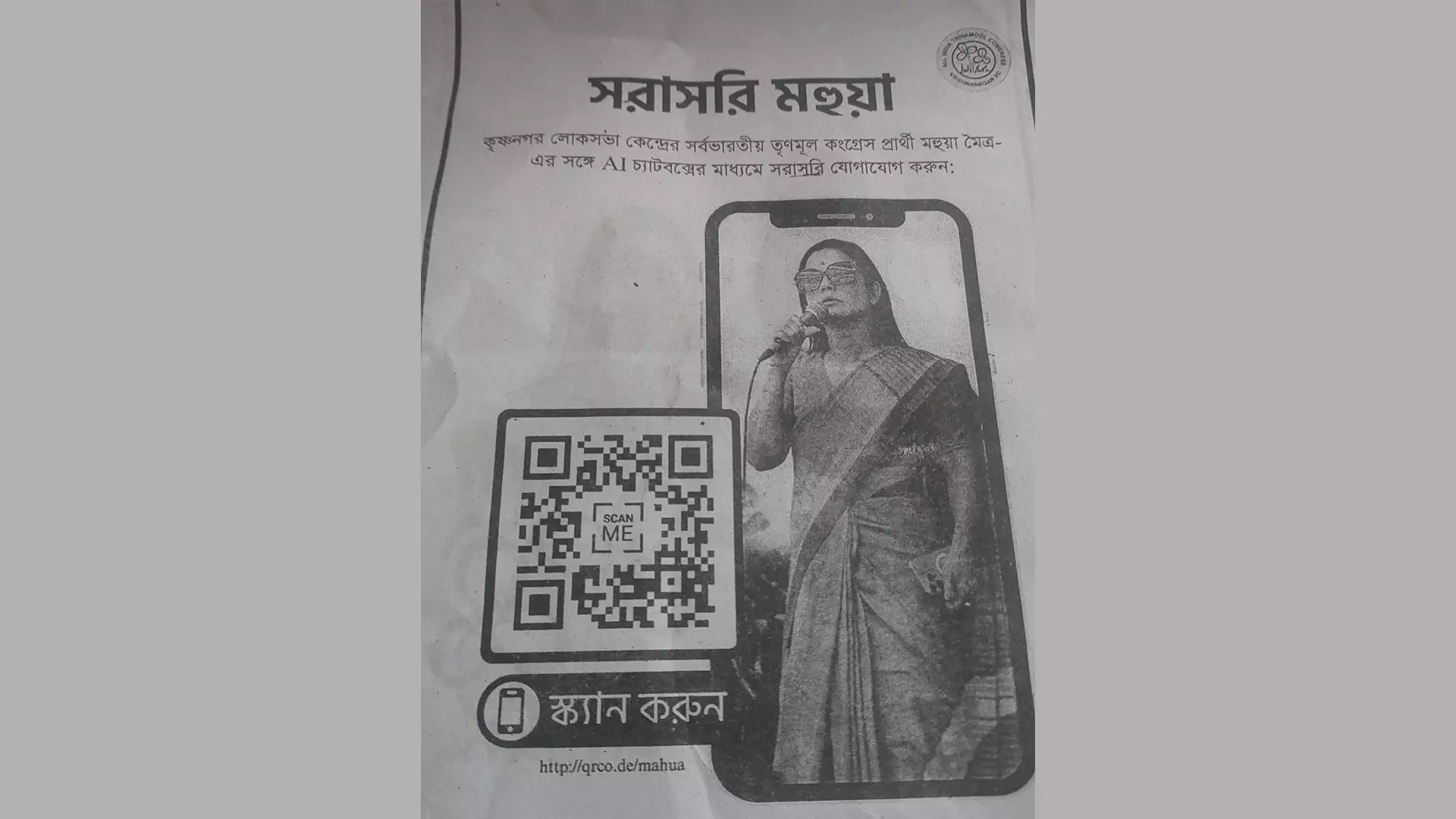

“We distributed leaflets containing a QR code. By scanning the code, one can directly connect with her through an AI chat box,” Ezra Mohanta, one of the ISD researchers attached to the firebrand TMC leader, told The Federal.

One of the key features of Mahua Moitra's outreach drive was direct interactions with voters through an AI chat box. One could connect to the chat box using a QR code.

Digital campaign is no doubt a great help to reach out to massive electorates in each of the Lok Sabha constituencies, said BJP’s media co-incharge in Bengal Kalicharan Shaw.

He said his party’s campaign is a mix and match of both traditional and digital campaigns.

With even the digital campaigning moving beyond convention with the growing use of AI, the dynamism in Indian democracy is unmistakable, said veteran journalist Ashish Biswas, who has closely seen the transition having covered elections for several decades.