- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

From maach bhaat to maach chapati: Why Bengal is ditching rice for roti

Bengalis often make fun of themselves calling them ‘Bheto’ because of their edacity for rice, bhaat in Bangla.This appellation may soon become a misfit as those running the state’s public distribution system (PDS) are of the view that the food habits of the community is changing, causing gradual increase in wheat consumption at the expense of rice in West Bengal. The state’s food...

Bengalis often make fun of themselves calling them ‘Bheto’ because of their edacity for rice, bhaat in Bangla.

This appellation may soon become a misfit as those running the state’s public distribution system (PDS) are of the view that the food habits of the community is changing, causing gradual increase in wheat consumption at the expense of rice in West Bengal.

The state’s food and supply department and fair price shop dealers have even ensured that the Union government takes note of the gustatory change by increasing wheat allocation for the state under two food subsidy schemes.

The Centre has recently increased the ratio of wheat for allocation under the Antodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) and Priority Household (PHH) for nine states — Bihar, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. The two schemes run under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) are collectively called Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY).

Chapatis on the platter

“West Bengal and a few other states had been urging the Centre to increase the allocation of wheat ever since it was slashed following the wheat crisis in the country two years ago. The states were forced to substitute wheat with rice. We particularly sought the hike in wheat allocation because there is a growing demand for the cereal in the state. We could not locally procure it as the state does not produce enough,” said an official of the department.

The official added that the curtailment had sparked resentment among ration card holders, prompting the state government to ask the Centre to revise the quantity of wheat allocation.

The allocation has been increased by 35 lakh metric tonnes with effect from October-November this year keeping in mind the state’s requirement, he added. The Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution issued an order in this regard on September 24.

“The allocation of rice and wheat under NFSA/PMGKAY is revised in respect of nine States i.e Bihar, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal,” read the ministry’s communique to the state.

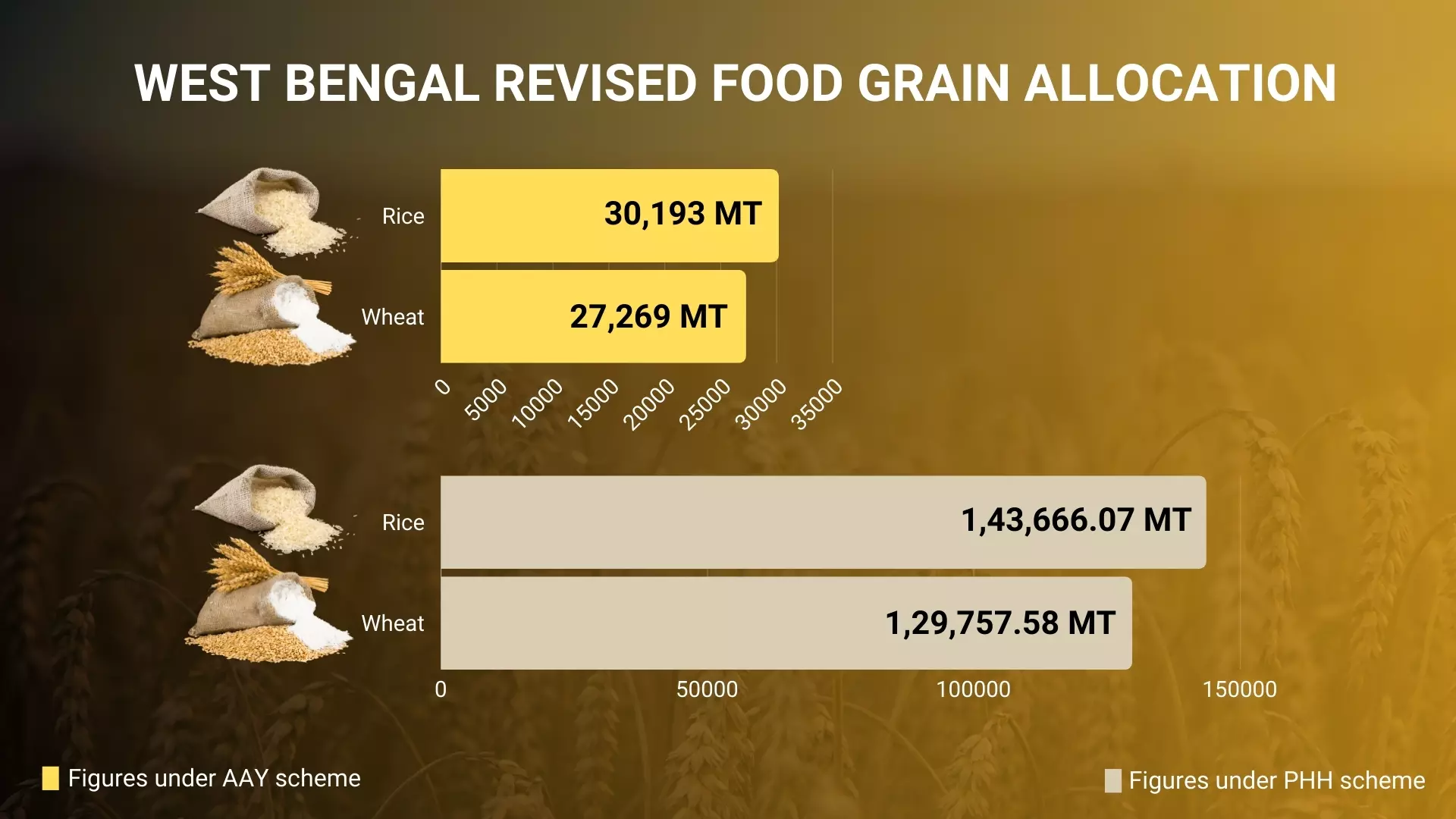

As per the revised allocation, West Bengal will now receive nearly 30,193 metric tonnes of rice and about 27,269 metric tonnes of wheat per month under the AAY scheme. For the PHH scheme, the monthly allocation will be 1,43,666.07 MT and 1,29,757.58 MT respectively.

The increased allocation will continue until March 2025.

Due to the change in allocation ratio, each PHH card holder will now get 2.5 kg each of both wheat and rice instead of 3 kg rice and 2 kg wheat per unit.

Similarly, AAY beneficiaries will now receive 18 kg rice and 17 kg wheat per card in place of 21 kg of rice and 14 kg wheat.

Roti or rice: What’s healthier?

Welcoming the hike in wheat allocation, General secretary of the All-India Fair Price Shop Dealers' Federation Biswambhar Basu said the Centre took note of the changing food consumption pattern in the state.

“Those sitting in the air-conditioned room might not have noticed it, but those of us dealing in food grains on the ground have been observing a steady increase in wheat consumption in Bengali households. Many families now include rotis at least in one daily meal,” Basu claimed.

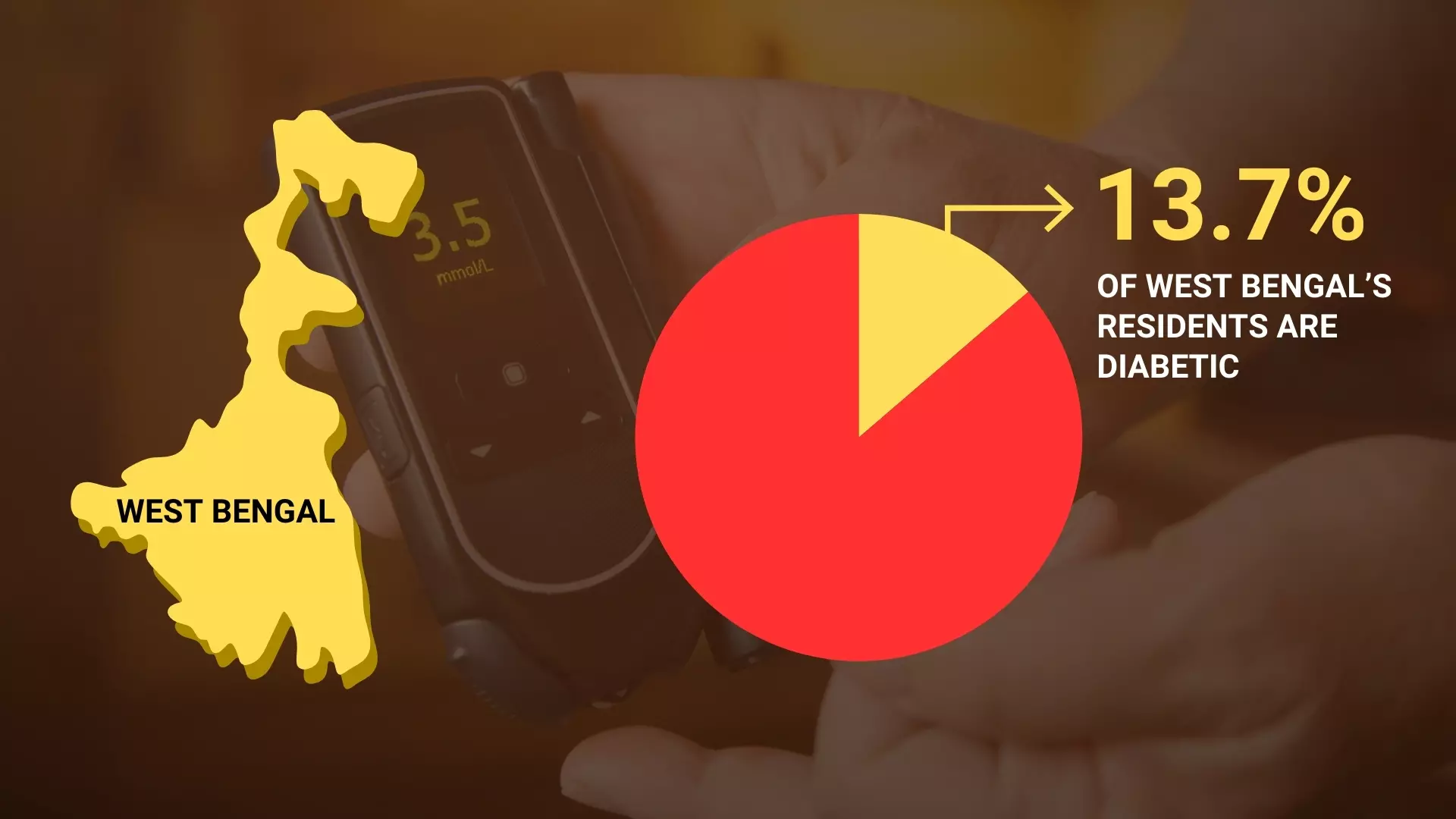

He said the change in consumption pattern could be because of the high prevalence of diabetes in the state.

According to a recent survey conducted by the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal, 13.7 per cent of West Bengal’s residents are diabetic.

Wheat is generally considered better than white rice for people with diabetes because it has a lower glycemic index (GI) and is a better source of fibre and protein.

The GI of wheat roti is 62 whereas white rice is 73.

A recent study of the Indian Council of Medical Research–India Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB), however, while emphasizing on reducing the consumption of white rice to manage diabetes, maintained that wheat is equally bad.

Nevertheless, many diabetic Bengalis are opting for rotis made of wheat to manage sugar levels, claimed Basu.

Mritunjoy Banerjee, a farmer and a retired teacher from Bankura, is one of them.

“I have stopped eating rice for dinner since I was diagnosed with diabetes six years ago. I take four chapatis instead of two bowls of rice,” he said.

Who is eating what

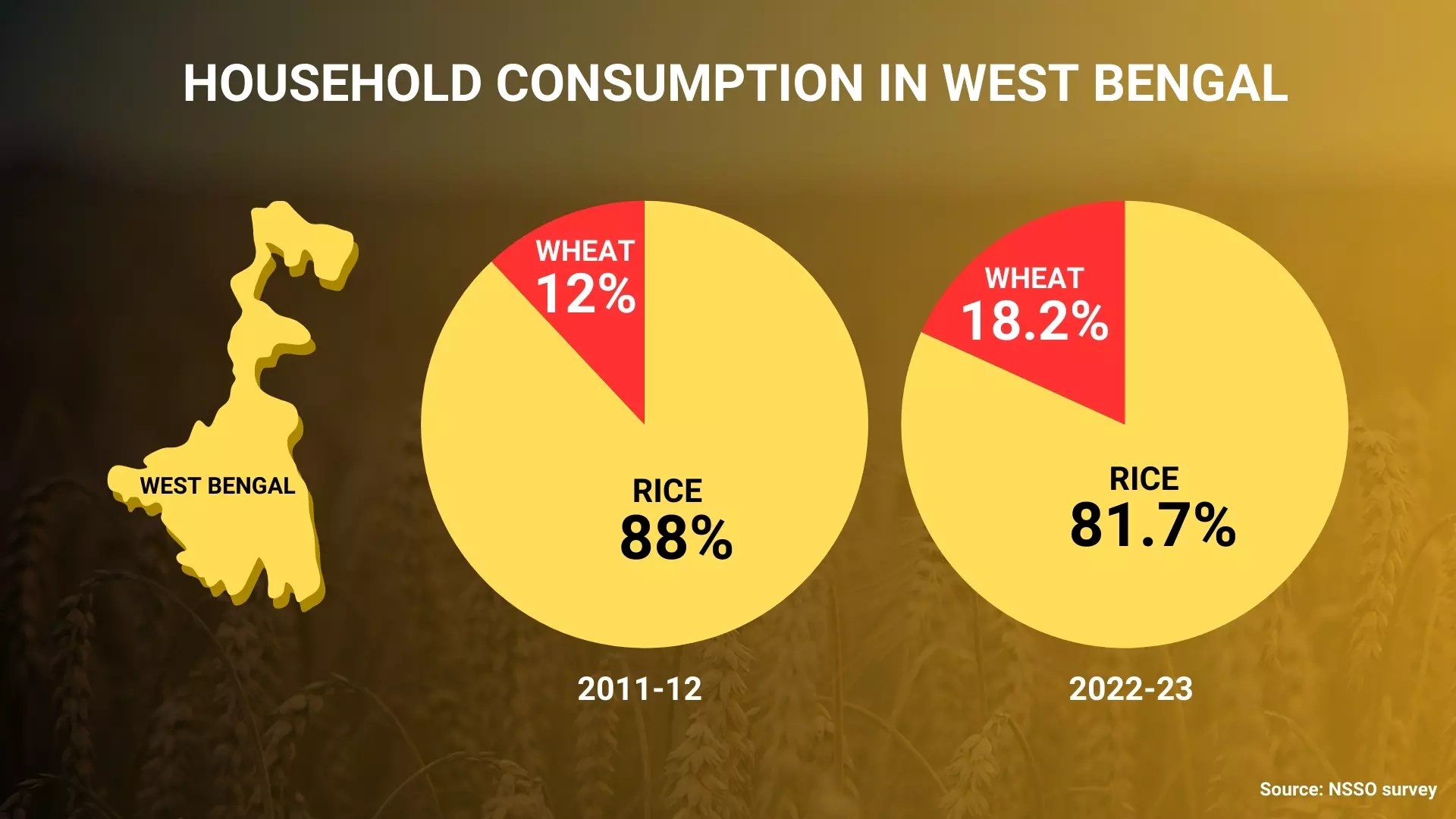

The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) survey on household consumption also indicated a spike in wheat consumption and fall in rice intake in Bengal in the past one decade or so.

For instance, 88 per cent was rice and 12 per cent was wheat of a rural household’s total cereal intake in Bengal in 2011-12. As per the latest NSSO survey, published earlier this year, the consumption of rice among cereals in rural households in Bengal dropped to 81.7 per cent whereas the wheat intake increased to 18.2 per cent.

In urban Bengal, the share of rice in the cereal bucket is 74 per cent whereas wheat is 25.9 per cent.

The production of wheat in the state, however, did not witness a proportionate growth. As per the data available with the state government the wheat yield decreased to 3000 kg per hectare in 2022 from 3077 kg/ha in 2021. The produce is stagnant at around 650 thousand metric tons.

One of the factors for the stagnation is vulnerability of the crop to diseases and extreme weather. This has forced the farmers to opt for cash crops such as lentils and maize.

Growing wheat in Bengal

The wheat cultivation in Bengal region got a push after research on the cereal crop was initiated by the Government of Bengal’s economic botanist in 1936. But it was not prioritised for commercial cultivation until the great famine of 1943. The famine was caused by the rice brown spot epidemic, apart from policy failures.

The ‘grow-more-food’ campaign launched after the famine emphasised on wheat cultivation. But due to lack of demand and other factors such as climatic conditions, farmers in Bengal never took to wheat cultivation in a big way.

After coming to power, Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress government tried to increase wheat production in the state. In 2013, the state set the target of increasing the production to around five million tonnes from 1.5 million tonnes within four years.

The ambitious plan was grounded following the outbreak of wheat blast disease in 2016 that had forced the state government to put a ban on wheat cultivation in Murshidabad and Nadia districts. The ban was enforced till 2022, driving farmers away from wheat cultivation.

West Bengal presently contributes only one per cent of the total wheat production in the country, leaving the state increasingly dependent on the central allocation to satiate the new-found love of Bengalis for chapatis.