- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

DV Gundappa: The man who challenged baksheesh for journalists is being remembered in 9 volumes

8 mins read

Hullagu BettadaDi, mange malligeyaguKallagu kashthgala maLe vidhi suriye Bella sakkareyagu deena durbalarige EllaroLagondaagu Mankuthimma. Be a (gentle) blade of grass at the foot of a mountain and jasmine, flower at home. Be (strong) like a rock when fate rains difficulties upon you. Be sweet like jaggery and sugar to the poor. Be one among all Mankuthimma.— Thus reads a popular maxims...

Hullagu BettadaDi, mange malligeyagu

Kallagu kashthgala maLe vidhi suriye

Bella sakkareyagu deena durbalarige

EllaroLagondaagu Mankuthimma.

Be a (gentle) blade of grass at the foot of a mountain and jasmine, flower at home. Be (strong) like a rock when fate rains difficulties upon you. Be sweet like jaggery and sugar to the poor. Be one among all Mankuthimma.

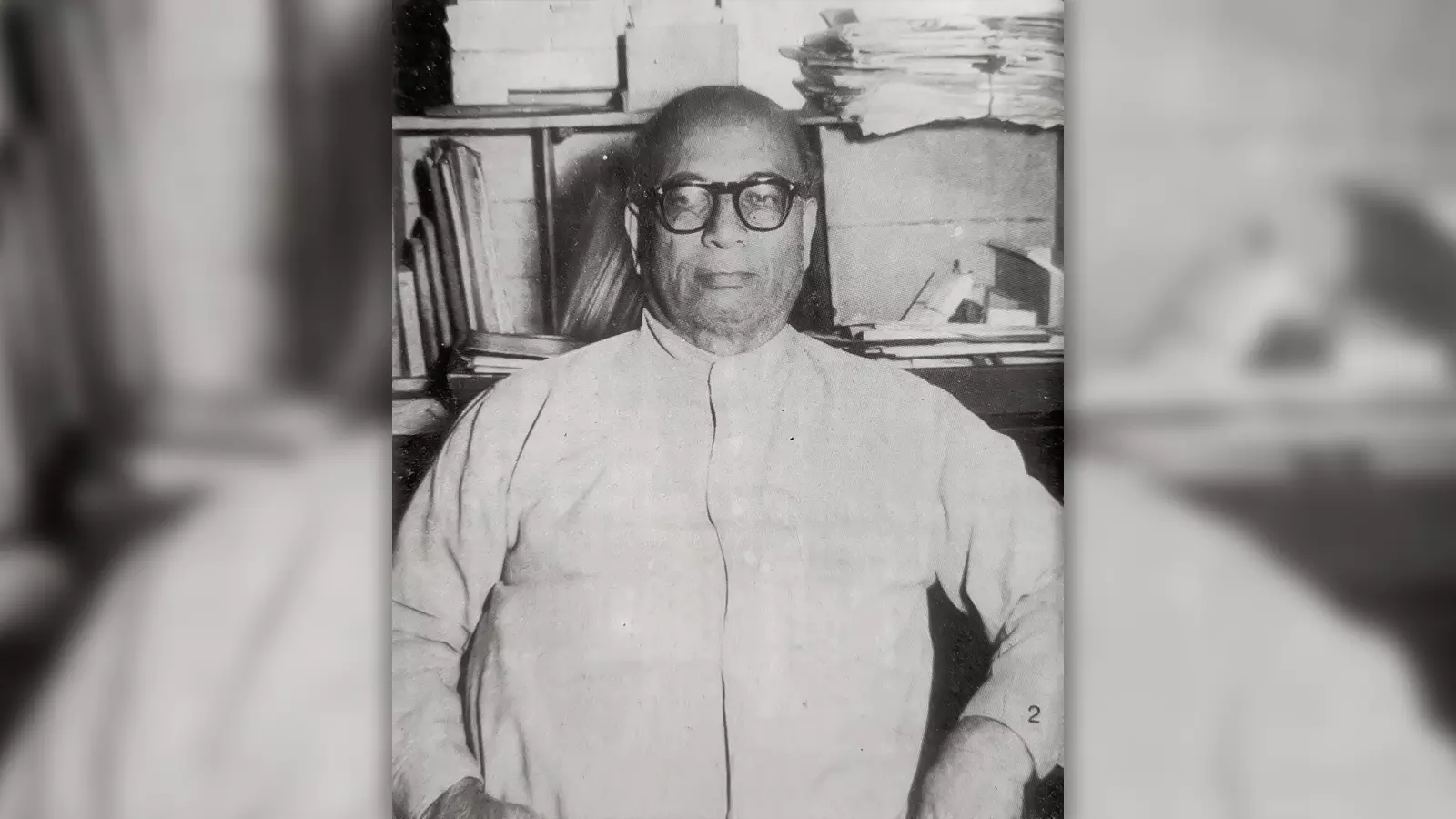

— Thus reads a popular maxims of 945 quatrain poems of Mankuthimmana Kagga — a classic of modern Kannada literature, which is a collection of verses capturing the musings on life in a semi-philosophical vein written by renowned scholar, writer, poet, and cultural chronicler Devanahalli Venkataramanayya Gundappa (1887-1975), popularly known as DVG.

For Kannadigas, Mankuthimmana Kagga, pulsating with DVG’s philosophises, holds the key to a balanced life, besides advocating oneness with people around.

While people who know Kannada have benefitted from the writings of DVG, his works have remained confined to Karnataka because his English writings, richer in volume, could never be formally and systematically taken to the audience.

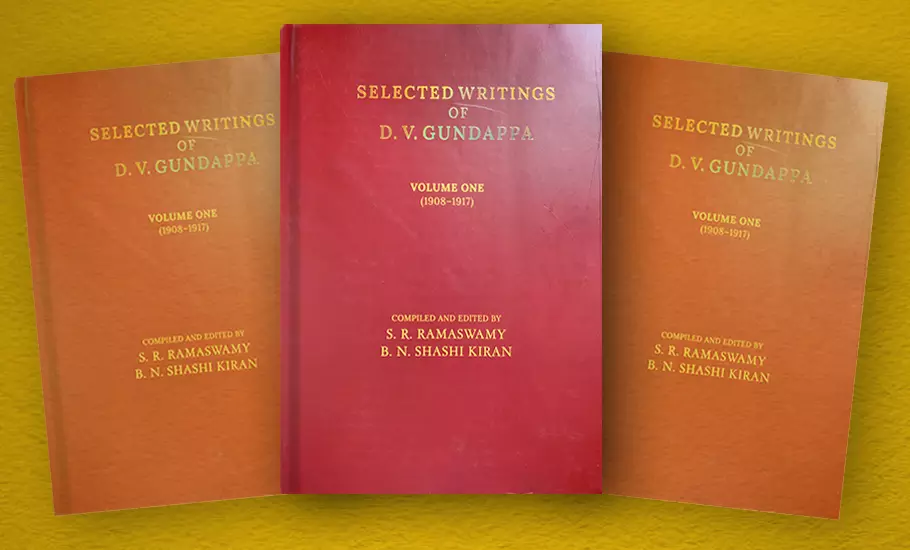

A concerted effort has now however been made in the direction. Selected Writings of DV Gundappa, a nine-volume collection has been brought out by the seven-decade-old Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs (GIPA), a Bengaluru-based institute of intellectual enlightenment, which was set up by DVG himself. The nine volumes of the work contain selected writings of DVG to mark the institute’s platinum jubilee. These volumes have been compiled by renowned scholars SR Ramaswamy and BN Shashi Kiran.

As his death anniversary — October 7 — approaches it is an opportune time to look at DVG’s legacy through his deeds and writings.

* * *

DVG was a man of principles, a facet which reflected as clearly in his literary works as his personal conduct.

Citing an instance when DVG stood to defend journalistic ethics, noted scholar, writer, and literary translator S Diwakar cites an instance where DVG took on the then dewan of Mysore, Sir M Visvesvaraya.

As his death anniversary — October 7 — approaches it is an opportune time to look at DVG’s legacy through his deeds and writings. Photos: GIPA/On arrangement

“Back then there was a government practice of paying baksheesh (cash as a present) to the newspaper representatives who went to the City of Mysore to report events such as Dusshera or festivities such as the birthday of the Maharaja. They were handed a secret largesse at the time of their departure from Mysore after the festival. The amount varied according to the supposed influence and standing of the paper. The transaction was a confidential one, not open to check or scrutiny by anyone,” Diwakar told The Federal.

“Under this system, DVG as the editor of The Karnataka was offered a similar baksheesh. DVG not only declined the money but also ensured that the system was brought to an end by taking it up with the dewan,” Diwakar added.

***

It is difficult to portray DVG in a single frame, as he was a consummate polymath. He was many things at once — a journalist, great visionary, poet, scholar, political analyst, social worker, and builder of institutions. The list is virtually endless. Evidently, the facets of his personality are varied and wide-ranging. A living testimony of DVG’s greatness is GIPA.

For many Kannada-speaking people, the three alphabets — DVG — evoke an image of a wise old man laughing a toothless laugh. DVG was known as Aadhunika Sarvanja (modern Sarvajna, Sarvajna being 16th century Sharana philosopher). He is still considered as Ashwatha Vruksha (peepal tree) of the Kannada cultural spectrum. Many Kannadigas are therefore startled by the fact that the nine volumes of Selected Writings of DV Gundappa cover his works written in English on topics such as law, politics, journalism and economics that are distant from philosophy, a theme richly covered in his Kannada works.

According to renowned linguist and writer Ha Ma Nayak, “DVG’s literature was one that combines Sathya (truth) Shiva (kind), Soundarya (aesthetical).”

Though DVG studied up to Class 10 but that didn’t deter him from pursuing writing. Significantly, DVG wrote more in English than he did in Kannada. A reliable estimate places the corpus of English at 15,000 pages, which is more than twice the volume of his works in Kannada.

DVG was a prolific writer who regularly commented on political developments at the national and regional levels for almost seven decades, particularly upholding a liberal and non-partisan viewpoint. A good portion of this staggering body of literature first appeared either in the columns of newspapers and journals that DVG himself edited and published or in the tracts he wrote as a response to the then-current issues of public life. These journals and tracts were not compiled or republished. Unsurprisingly, DVG’s English writings have remained inaccessible. This is perhaps why DVG remains largely unknown outside of Karnataka.

GIPA’s initiative is thus helping in taking DVG’s messages to a wider audience. “We will bring out another two volumes in the next few months to help people understand DVG’s contribution to society,” says Shashi Kiran, one of the two compiling editors.

DVG was a systematic, truthful, and caustic conscience-keeper of independent India’s political and social conscience. The nine volumes mirror the socio-political, economic, and cultural churning of society as seen through DVG’s unique lens.

Journalistic morality

The prologue and epilogue of DVG’s journalistic story in Volume I (1908-1907) share a section on his fearless, hard-hitting protest against governmental regulations curbing public freedom. At a time when journalism has mostly been reduced to a racy reportage of colourful caprices, half-truths, and straight propaganda, DVG holds greater relevance today than he did in his own time. He repeatedly warned members of the journalistic fraternity against these precise professional evils. The first volume presents a collection of his writings published from 1908 to 1918, arranged chronologically.

“This volume contains extracts from DVG’s earliest extant book-length writing, a forceful protest against press censorship. His mastery over language and over political history may be seen even in these early writings,” BN Shashi Kiran told The Federal.

Volume II (1917–1922) also delineates issues related to DVG standing to defend the freedom of press. His standards were exacting and DVG made sure that he practiced what he preached. His essays and editorials in The Karnataka unceasingly celebrated enduring values such as gratitude, trustworthiness, independence, courage, and candour.

The subsequent volumes cover DVG’s writings published in The Karnataka and The Indian Review of Reviews. The writing in these volumes deal with problems of Indian Native States in the context of emerging dispensation and there are few articles on political and economic development of Mysore. There are articles that deal with political developments at the national level at the penultimate stage of the struggle for Independence.

His mid-1940s writings are seminal considering they were borne in his mind when the Constitution of Independent India was being conceived. Likewise, there are journalistic pieces that reflect the agility of DVG’s intellect, keen observation, vast range of interests’ analytical acumen, and felicity of expression. There are recordings of his speeches on stalwarts of Indian politics in the pre-Independence era such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale and VS Srinivasa Sastri. The importance of these volumes lies in DVG’s recording of statecraft and polity, linguistic problems, inheritance laws and industrialisation.

Review in ‘The Spectator’

DVG brought together his considered views on the problems of Native States in a monograph titled The States and their People in the Indian Constitution. This small volume received critical appreciation from the press both in India and abroad. CF Andrews reviewed this 200-page classical work in The Spectator, a periodical published in London.

“It is a well-arranged and documented review of one of the most difficult subjects. The author is outspoken in his disappointment at the Princess’s attitude during the earlier Conference sessions. They bluffed and in the end surrendered nothing at all. They entrenched their own position, as arbitrary Rulers, at the expense of their subjects. Mr. Gundappa hopes that at the next session, the leading Indian statesmen will not barter away as they did before, the rights of the Indian States subjects.”

The fourth volume has references to The States and their People in the Indian Constitution.

National treasure

“However, it is hard to draw a strict line of demarcation between the publicist and the man of letters, as DVG himself did not compartmentalize his activities in this manner. On the contrary, he looked at life as an ‘undivided whole’. DVG is a national treasure, and it is only right that all Indians should know him well. But given our wanton disregard for native scholars, many people outside Karnataka do not know him,” observes Shashi Kiran.

One can regard the legacy of DVG from the three-tiered perspective; public life, litterateur and philosopher, that his life and work represents: DVG served as a Member of the Legislative Council in the Government of Mysore from 1927 to 1940. Incidentally, these years demanded his active participation in various non-political activities connected with the Mysore University and Kannada Sahitya Parishat. He was a member of the Constitutional Reforms Committee of Karnataka (1938-1939). Regardless, true to his stature as a sincere spokesman of public interest, DVG championed the cause of several reformist measures such as child marriage, controlling proselytization, securing temple entry to Harijans, and legitimising the teachings of the Vedas to non-Brahmin students.

The Kannada contributions

DVG’s contribution to Kannada literature is immense. Over 35 literary works were published by DVG during his lifetime. This included 11 works of poetry, 7 biographies, 5 plays, and 2 works of literature for children. Of these, Mankuthimmana Kagga is the most well-known. This collection of 945 poems was published in 1943 and has since been translated into English, Hindi, and Sanskrit. These poems throw light on the different aspects of life and advise people to live and grow in harmony with the people around them and their surroundings.

DVG wrote more than 20,000 pages in English and Kannada. While his English writings largely deal with politics and rarely foray into culture, literature, and philosophy, his works in Kannada cover a wide range of literary genres. DVG’s translations of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyats and Shakespeare’s Macbeth are landmarks in Kannada literature. While the translations are themselves splendid, the introductions that DVG wrote to these works, are worthwhile. His analysis of Lucretius, Robert Browning, and Omar Khayyam from the perspective of Vedanta is remarkable. The perspective, he brings to bear on the analysis of tragedy is unique and profound. DVG’s thoughts on literature and literary theory are fresh and valuable. He was of the firm opinion that poetry should have a positive bearing on human life.

“Today in India, we proudly assert our civilizational identity. At this juncture, it is crucial to adopt the attitude of critical conservatism. We should strike a healthy balance between past experiences and present. DVG shows us the way to reconcile tradition and modernity, order and progress, precept and practice, form and content,” says Shashi Kiran.

DVG was calm and content within himself because he had the wisdom to reconcile the disparity inherent in the world. This internal serenity manifested as grace in his conduct. According to scholar Satavadhani R Ganesh, “The greatest learning from DVG’s personality is perhaps the following — celebrate life, value joy over achievement, abandon stubbornness. Pursue what you love, be grateful for what you have, help people around as much as you can, find harmony in dichotomy, follow the path of the golden mean, and most important of all, don’t take yourself too seriously.”

“DVG can help us in honing our expression. He wrote in a lucid, engaging and intimate style. When we read his works, we feel that he is physically present with us, absorbed in friendly conversation. He had the uncanny ability to present the most complicated of subjects in the simplest and most cogent manner, without even playing it down. He could do this because he had internalized all the subjects he wrote about. The world today is hurtling forward at a dizzying pace. Easy and widespread access to information has led people to adopt an almost irreverent attitude to wisdom. Reason seems to be lost between jingoistic assertions and blithe dismissals. DVG can help us rise above these abysmal trends. We will do well to pay him heed when he describes the features of an objective mind,” observes Shashi Kiran.

Being a journalist, he founded and edited numerous newspapers and journals; Sūryodaya-prakāśikā, Bhāratī, Sumati, Evening Mail, Mysore Times, The Karnataka, Karṇāṭaka Janajīvana mattu Arthasādhaka Patrikè, The Indian Review of Reviews and Public Affairs and Bharat.

A nine-volume collection on DVG’s works has been brought out by the seven-decade-old Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs.

He frequently wrote for leading Indian newspapers like The Hindu. Though The Karnataka started off as an English magazine, it was soon transformed into a Kannada publication. Through the publication division Sumathi Granthamale, he also published a dozen small books, including the biography of Diwan Rangacharlu. DVG founded social organisations and guilds and worked tirelessly for people’s welfare. He lived like a sage till the last, moving easily with rich and poor, bureaucrat and labourer, scholar and unschooled.

Jnanpith missed, Kendra Sahitya Akademy award won

DVG looked upon public life as a sacred service. And service accepts no reward. In keeping with this view, he maintained a healthy distance from riches. He did not encash even one of the many cheques that the treasury of the Mysore State issued for his services, as a consultant to Sir M Visvesvaraya, the then dewan. He remained fiercely independent throughout his life. Never did he seek recognition.

When the Jnanpith Award was first instituted, Mankutimmana Kagga came before it for consideration. But DVG’s work was not considered. When his friends expressed regret, DVG consoled them in his signature characteristic self-effacing, humorous style. He felt that the idea of competitive prizes for literature is basically absurd. Vyasa, Potana, and Thyagaraja are his ideals as they did not compete for anybody’s favour. But DVG received the Kendra Sahitya Akademi award in 1967 and the prestigious Padma Bhushan in 1974.