- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Children who work and don’t go to school or get to play

Ten-year-old Pinky Das walks in and around Maligaon in Assam’s Guwahati from morning to afternoon as she collects waste materials from garbage bins and roadside trash.Her tiny hands rummage through rubbish dumps. She carefully picks discarded bottles, cardboard, books, plastic packets, wire, fused bulbs and anything and everything “useful” and puts them inside a gunny sack that slings...

Ten-year-old Pinky Das walks in and around Maligaon in Assam’s Guwahati from morning to afternoon as she collects waste materials from garbage bins and roadside trash.

Her tiny hands rummage through rubbish dumps. She carefully picks discarded bottles, cardboard, books, plastic packets, wire, fused bulbs and anything and everything “useful” and puts them inside a gunny sack that slings over her right shoulder.

She accompanies her widowed mother, Bondita Das, 33, a ragpicker. Both mother and daughter stay in a shanty near a railway line passing through Maligaon, a bustling business hub in the city.

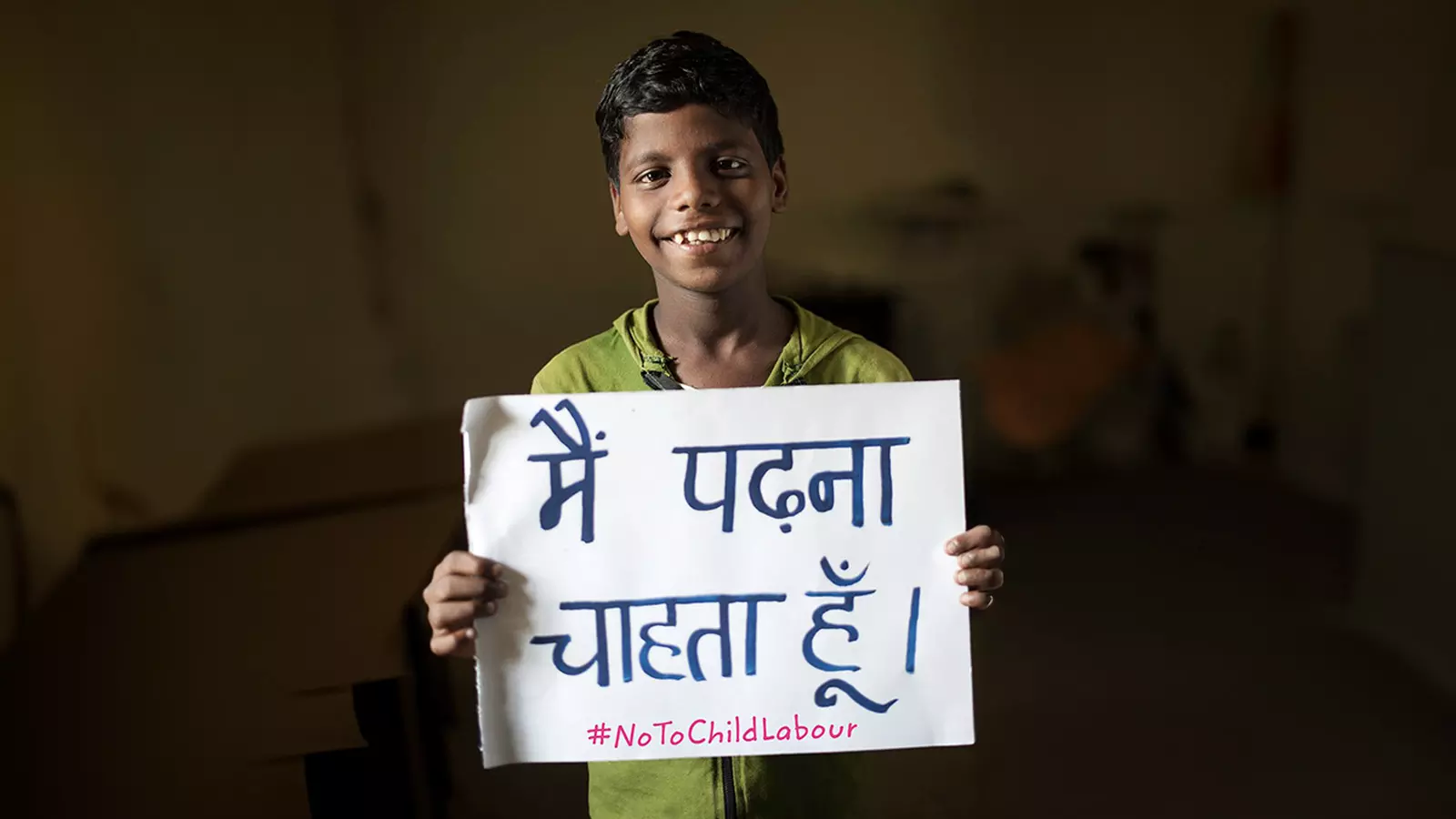

A child holding a placard expresses his desire to study. He condemns child labour. Picture courtesy: UNICEF India

Bondita tells The Federal that Pinky has been helping her for almost three years. “Together we collect 40-50 kilos of waste every day. We sell them to the neighbourhood kabariwallah (scrap dealer). We earn around Rs 100-150 a day.”

A daughter's wish and a mother's lament

Pinky interrupts her mother and adds that she wants to go to school. Bondita replies, “I too wish to send my daughter, my only child, to school and give her a good education. But I can’t afford to do it. After my husband died, four years ago, I am the sole breadwinner. I take Pinky's help to collect more waste and earn a little more.”

Pinky gasps and grimaces listening to her mother. Bondita holds two flattened plastic bottles of a popular beverage in her hands before putting them in her gunny sack. After a while, the 10-year-old says, “Can I say something? I want to play too like other children.”

This time, Bondita remains quiet.

Will marking days against child labour end the misery of poor kids?

Ironically, the conversation between Pinky and Bondita took place on June 12, observed globally as the World Day Against Child Labour. A day before, on June 11, the inaugural International Day of Play was celebrated.

A poster shared by Karnataka Pradesh Mahila Congress on the occasion of World Day Against Child Labour on X.

Both these events were part of the United Nations to "make the world a better place for children by providing them with protection, education, health care, shelter and good nutrition, under the Declaration of the Rights of the Child". The Declaration, adopted in 1959 by the United Nations General Assembly, is a foundational document of international law related to children’s rights.

Both Bonita and Pinky are unaware that international laws and treaties like the Convention on the Rights of the Child (of which India is a signatory) exist to provide basic needs for children from underprivileged sections.

A struggle to get an education

Almost 2,700 km from Guwahati, in Karnataka’s Bengaluru, Lavanya Devi, 17, sells vegetables in a makeshift shop with her father Ramesh Kumar, 40. She is a school dropout. In 2020, when Ramesh’s earnings dwindled to zero during the coronavirus pandemic, Lavanya and her younger brother Lokesh's education came to a halt.

“It was a tough time. My father could not open his shop due to restrictions imposed by the government to stop the spread of the virus. My mother, a domestic help, also lost her job. Both did not earn anything. We survived on little money they had saved,” Lavanya said.

“Our classes shifted online. We did not have smartphones or laptops. So we could not attend classes and missed our exams. Afterwards, I did not go back to school when it reopened. My brother resumed school in 2021. I help my father in his shop during evening hours and work as a maid in two households during the day,” Lavanya added.

The pandemic brought permanent problems to the poor

Dalit and child rights activist from Karnataka Y Mariswamy told The Federal the dropout rate of children from Dalit and other marginalised groups has increased post the pandemic in the southern state.

According to reports, as schools across India shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s dropout rate increased from 1.8 per cent in 2018 to a staggering 5.3 per cent in 2020. This predominantly impacted children hailing from marginalised communities, exacerbating existing inequalities.

"Thousands of people from these communities working in the informal sector have lost their livelihood during the coronavirus. They are still struggling to stand on their own feet. Those who can't pay school fees and other related expenses have stopped sending their wards to schools," added Mariswamy.

During the pandemic, 84 per cent of households reported income loss across the country.

"The government has failed to take the initiative to help dropout children resume their education," said Mariswamy.

Losing education, losing childhood

Activists allege governments, at the centre and in states, are violating the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act of 2009. As per the Act, every child between the ages of 6 and 14 has the right to free and compulsory education.

A rally to mark World Day Against Child Labour in Bengaluru, Karnataka.

"In Guwahati (the city is known as the gateway to Northeast India), hundreds of children are out of school. They are either working as child labourers doing odd jobs or are loitering around doing nothing. They are losing their precious childhood. They are losing their chance to get an education,” said Bhaskar Kalita, an Assam-based activist who works with marginalised communities.

The rise in school dropout of children is also leading to an increase in child marriages. One in five girls and nearly one in six boys are still married below the legal age of marriage in India (which is 18 for females and 21 for males), a study published in the Lancet Global Health in December last year stated.

Reports suggest that many children, particularly boys, have developed an alcoholism problem and indulged in substance abuse.

Law versus reality

In India, the Constitution explicitly prohibits children under 14 from working in mines, factories, or hazardous occupations. Similarly, the International Labour Organisation defines a child as anyone below 18 who should not be involved in hazardous work.

“According to the Census 2001 figures, there are 1.26 crore working children aged 5-14 years. As per Census 2011, the number of working children in the same age group reduced to 43.53 lakh. In the absence of the current decennial Census, which has been indefinitely delayed, we do not know the change in this crucial data,” Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge stated in a post on X on June 12.

He added, "Every child is entitled to health, education, and protection. Child labour is a social crime. The enactment of Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 is a national endeavour which has considerably reduced child labour in India. However, in recent years, due to certain legal amendments and cuts to the child protection budget, combined with the impact of COVID-19, there have been reports of children being forced back into exploitative labour. On World Day Against Child Labour, let us commit to safeguarding childhood and eliminating child labour in India."

The number of child labourers in India is mindboggling. "These children often work in dangerous and unhealthy conditions in factories and brick kilns. The minors are vulnerable to violence and ill-treatment. Simultaneously, they are robbed of a normal childhood. They have no access to education, healthcare facilities, nutritious food nor the time to play and grow,” said Nagasimha Rao, a child rights activist from Bengaluru.

A time to play and forget the woes

Recognising the importance of play for children’s development, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out “the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities”.

Children having some fun time at a park in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh: Picture courtesy: UNICEF India

In March 2024, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution establishing June 11 as the International Day of Play to champion and protect this right.

“Play is how children learn to navigate the world. It helps them to build narratives, knowledge and social skills. It contributes to their overall development, including physical health, cognitive development and emotional well-being,” stated the United Nations Children's Fund or UNICEF.