- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Bloodlines of freedom: How Bangladeshi women fiction writers write about the 1971 war

The Bangladesh Liberation War had lasted for nine months, from March 25 to December 16, 1971. But those nine months, as Tahmima Anam writes in her novel, A Golden Age (2007) — the first of a trilogy that traces the birth of Bangladesh, and its tumultuous journey from a state to a nation — “were like nine generations, brimming with lives and deaths”. A Golden Age, and its sequel, The...

The Bangladesh Liberation War had lasted for nine months, from March 25 to December 16, 1971. But those nine months, as Tahmima Anam writes in her novel, A Golden Age (2007) — the first of a trilogy that traces the birth of Bangladesh, and its tumultuous journey from a state to a nation — “were like nine generations, brimming with lives and deaths”. A Golden Age, and its sequel, The Good Muslim (2011) delve into the aftermath of the war with a rare and piercing insight, foregrounding the pangs of a nation’s struggle for identity through the intimate fractures in a family. Rehana Haque, whose story forms the universe of the first novel, is neither an emblem of national pride nor a passive victim of circumstances. She is a widow caught in the brutal collision between personal love and the demands of a newly created nation. As a mother whose two children get involved in the war efforts, she remains committed to a cause larger than herself.

Bangladesh-born Anam (48), who lives in the UK now, belongs to a clutch of women writers from the country who revisit this phase from a women’s perspective in their fiction; they tell the untold stories, explore the silences, and give voice to the experiences of countless women who lived through the horrors of the conflict. Rehana’s journey is only emblematic of the turmoil faced by hundreds and thousands of women during this period for whom the fight for independence coincided with battle for personal survival. Through Rehana, Anam explores the moral ambiguities of war, when the lines between right and wrong, loyalty and betrayal, personal and political get inevitably blurred. This exploration is not confined to the battlefield; it seeps into the very fabric of daily life, affecting relationships, identities, and the women’s sense of self.

Rehana’s home, once a fortress of her private grief, becomes a reluctant sanctuary for ‘freedom fighters’, a place where the walls echo with whispered secrets, and unspoken fears. Anam does not allow Rehana the comfort of clear-cut morality; her actions are driven not by ideology but by a fierce, almost primal, need to protect her children. One can argue that Anam, from the vantage point of her gender, presents war as an entity that doesn’t merely disrupt women’s lives, but devours, consumes, and reshapes their very fabric. As a mother, Rehana’s life is steeped in contradiction; she would move mountains for her children, but as a woman she is also torn apart by the knowledge that the same war that could give her children freedom might also take them away.

This duality runs like a dark thread through Anam’s novels, challenging us to consider whether the price of freedom is ever truly worth paying. Is Rehana’s involvement in the war a brave stand for justice, or is it a desperate act of love? Anam offers no easy answers, instead leaving the readers to grapple with the unsettling reality that war often demands the sacrifice of both ideals and innocents. Memory plays a treacherous role in A Golden Age, serving as both a guide and a tormentor. Rehana’s recollections of her late husband and the agonising loss of her children to the state before the war began are not just personal scars; they are symbols of a nation’s collective trauma. Anam insists that the personal is inextricable from the political, that the stories of women like Rehana are the very threads from which the fabric of history — often dominated by the sacrifices of ‘revolutionary men’ — is woven. The novel ends on December 16, 1971; Rehana’s memories become a battlefield of their own, where the ghosts of the past refuse to rest, and the promise of a better future is tinged with the blood of the present.

In The Good Muslim, Anam shifts her focus to the wreckage left behind after the guns fall silent. The novel focuses on the disillusionment of a nation grappling with the bitter truth that independence is not a panacea for the wounds inflicted by war. Maya, Rehana’s daughter, returns to Dhaka to find a country still haunted by the war’s spectres, its ideals eroded by the harsh realities of power and politics. The novel’s title, The Good Muslim, is soaked in irony, a question rather than a statement, as Anam probes the hollow certainties of faith in a world that has seen too much bloodshed. Maya’s brother, Sohail, exemplifies the nation’s tussle between secularism and religious conservatism — a struggle that threatens to tear apart not just the country but the family itself. Anam portrays Sohail’s descent into religious extremism not as a sudden fall but as a gradual unravelling, a process born from the same war that once promised to deliver freedom. Anam seems to drive home the point that even the most righteous of wars can give birth to new forms of oppression.

Sohail’s transformation — from a believer in secular ideals to a hardcore fundamentalist — is a mirror to Bangladesh’s own troubled evolution; it brings to the fore the uneasy reality that the lines between hero and villain, saint and sinner, are often drawn in sand, easily erased and rewritten. Maya, in contrast, clings to the ideals of the Liberation War, even as she witnesses their erosion in the face of rising conservatism. Her work as a doctor and her quest for justice are not just acts of defiance against the new order but desperate attempts to salvage the remnants of a dream that is slipping away. Anam’s portrayal of Maya is layered; she is not a saviour, but a survivor, fighting not just against the forces of extremism but against the crushing weight of disillusionment.

The post-war Bangladesh that Anam depicts is a place where the past refuses to die, where the quest for a just and fair society is a battle that must be fought anew every day. Her novels refuse to offer the comfort of closure. Instead, they lay bare the attempts to define the legacy of the 1971 Liberation War, an endeavour that continues to shape the nation’s identity in ways both profound and painful. She forces us to confront the uncomfortable truths that history often seeks to hide. And understand that the gashes of war do not heal easily, that the cost of freedom is often borne by those least able to pay it.

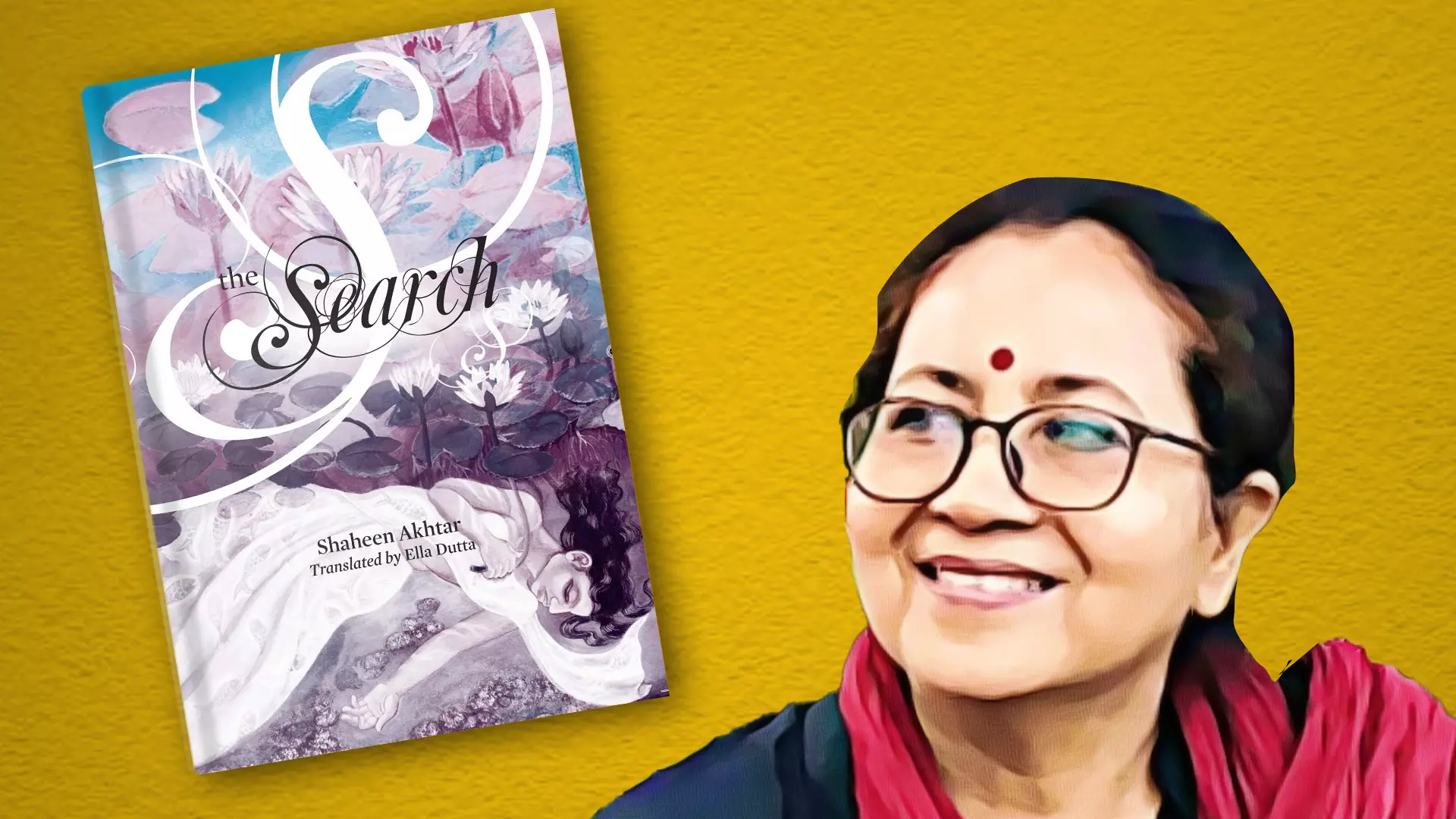

Shaheen Akhtar’s novel The Search (translated from the original Talaash by Ella Dutta) — haunting, to say the least, not just for its portrayal of physical and emotional damages but for its unflinching examination of the social ostracism faced by women — is a searing exploration of the harrowing experiences of sexual abuse by Bengali women during the 1971 war, when an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 women were subjected to rape, assault, and, in many instances, murder by West Pakistani forces. The novel, through the lens of a young researcher named Mukti, who is intent on writing about the survivors of wartime sexual violence, pieces together the fragmented — and traumatic — histories of these women, many of whom were held as sex slaves in military camps. Akhtar illuminates the persistent anguish, suffering, and unhealed wounds that linger two decades after the war.

Shaheen Akhtar’s novel The Search is a searing exploration of the harrowing experiences of sexual abuse by Bengali women during the 1971 war.

The term, birangana (war heroine), used to describe the women raped by Pakistan army, Razakar paramilitaries, and their local collaborators as symbols of national honour, is ironical in Akhtar’s work as it exposes the deep-seated hypocrisy of a nation that violates the honour of these very women during the war. Through the story of Mariam, a rape survivor, Akhtar (62), author of several collections of short stories and four novels, interrogates the notion of honour, questioning who gets to define it and at what cost. Like many women, Mariam was abandoned by her lover, Abed Jahangir, a student leader at Dhaka University, who made her pregnant (and subsequently by other men), at a time when the flames of the independence movement consumed all other considerations.

Mukti, whose name means ‘freedom,’ unravels Mariam’s story, and in the process, many other Biranganas, revealing the intersection of personal and national histories. Born on the night of March 25, 1971, as Operation Searchlight unleashed its terror across Bangladesh, Mukti is like Saleem Sinai, the protagonist in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, whose life is inextricably tied to the fate of her nation. Through Mukti’s search for truth, Akhtar shines light on the uncertainties that arise when a nation’s collective memory is fraught with unresolved trauma. It leaves you wondering about the cost of freedom for a woman like Mariam — it’s a freedom paid for not just in blood, but in her dignity and desire ‘to live, get married and have a child to raise’. Needless to say, the novel is an indictment of the ways in which women’s bodies become battlegrounds in times of war, not just for the physical violence inflicted upon them but for the emotional violence that continues long after the conflict has ended. Akhtar also critiques the nation’s failure to protect and rehabilitate these women; in the din of nationalism, gender violence often remains a footnote.

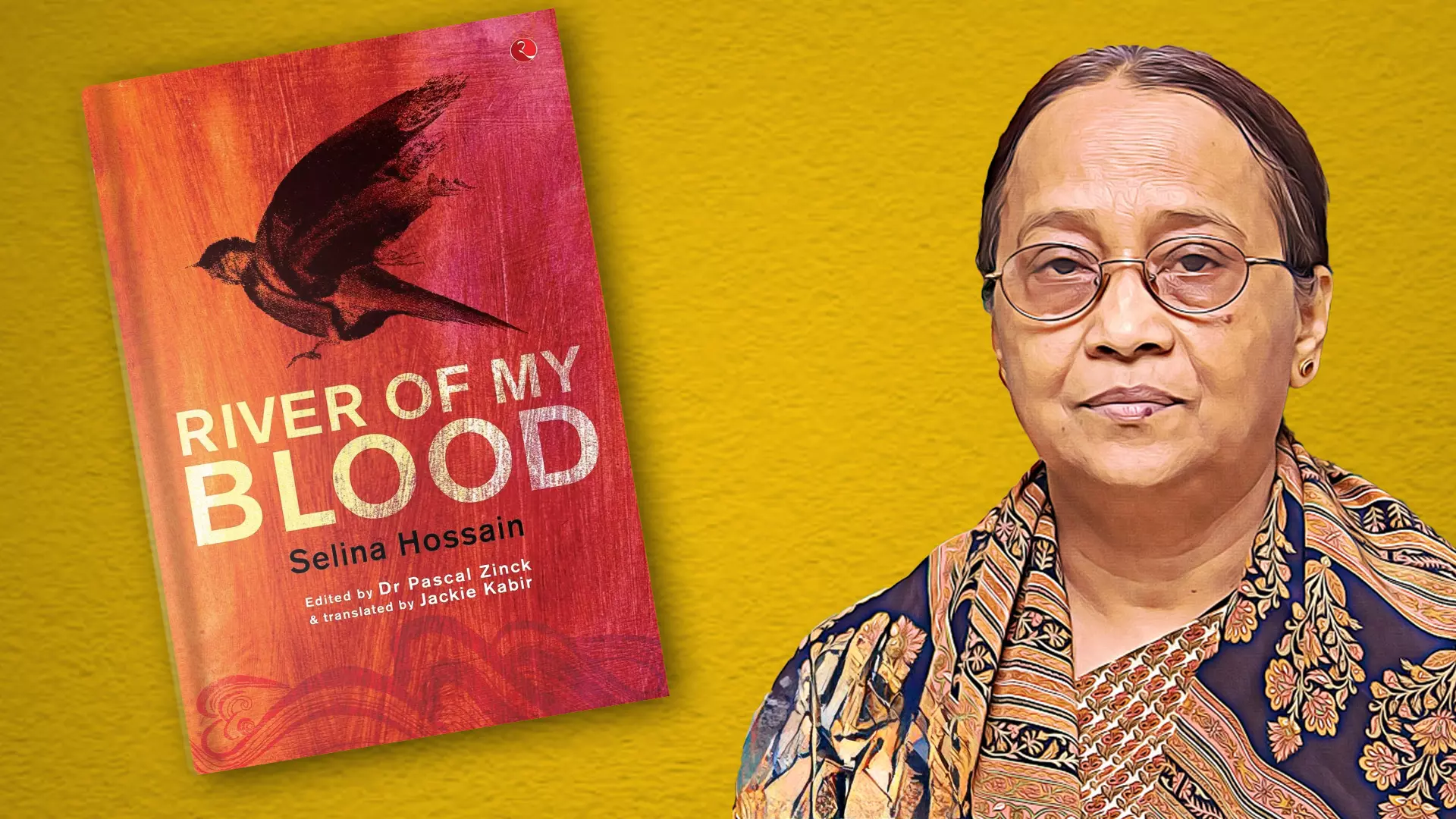

Selina Hossain (74), in her novel River of My Blood (Hangor Nodi Grenade, translated by Jackie Kabir), offers yet another perspective on the Liberation War, through the life of Buri, a woman whose personal tragedies are inextricably linked to 1971. The novel is rooted in the cultural and social milieu of rural Bangladesh, providing a stark contrast to the more urban settings of Anam’s and Akhtar’s works.

Selina Hossain, in her novel River of My Blood, offers yet another perspective on the Liberation War, through the life of Buri, a woman whose personal tragedies are inextricably linked to 1971.

Buri, a spirited girl, has to grapple with a harsh marriage, infertility, and the birth of a deaf and mute son. The crisis in her personal life mirrors the national crisis unfolding around her in Haldi, her village in East Pakistan, as it is engulfed by Muktijuddho — the nine-month war that led to Bangladesh creation as a sovereign state. Her personal travails only get compounded by the external horrors of war as Boori finds herself powerless against the relentless violence of the Pakistani army, which ravages her village and leaves her a young widow, faced with an unimaginable choice.

Rizia Rahman’s Letters of Blood, translated from Rokter Okkhor (1978) by Arunava Sinha, gives a glimpse of the women in prostitution in post-war Bangladesh. A departure from the traditional war novels, it is the story of a forgotten woman who is left to fend for herself once the war ends, and the physical and psychological toll of life in brothels in the Bangladesh of 1970s and 1980s. Rahman (79) does not shy away from the visceral realities of this world, and imbues her characters with a dignity that transcends their circumstances. Scores of women born into poverty are thrown into prostitution, sometimes by the helpless family members themselves. In the ‘Author’s Note’ of the novel, Rahman writes: “I had written the book many years ago, reflecting the situation then. What is disappointing is that their actual condition has not really changed at all.”

Rizia Rahman’s Letters of Blood gives a glimpse of the women in prostitution in post-war Bangladesh.

These novels challenge the official historiography of the war, which is preoccupied with the heroism and sacrifice of the fighters, and limn the experiences of those who were left behind, those who bore the brunt of the war, and those whose stories have been silenced or forgotten. They also raise important questions about the nature of memory and history. Memory, in these works, is not a static record of events but a dynamic process of negotiation, where the past is constantly being reinterpreted in light of the present.

The characters in these novels — at odds with the new nation, as they grapple with the disillusionment (this is particularly acute for women, who find that the promises of liberation often ring hollow in a country that continues to oppress them) that comes with independence — are often engaged in acts of remembering and forgetting, as they strive to come to terms with the contusions of the war. This process is filled with contradictions, as the need to remember is often discordant with the desire to forget, to move on, to rebuild. The tension between these impulses is a central theme in the literature of the 1971 war written by women. Last, but not the least, they make us think about how to commemorate and make sense of the past, and how not to lose sight of its gendered nature.