- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Kareena Pradhan* was 11 when her parents — labourers at a tea garden in India’s north-eastern state of Assam — sold her to a trafficker for Rs 2,000. Her buyer then sold her to a family in Arunachal Pradesh, a hill state that borders China and Myanmar in the extreme northeastern part of India, to do household chores. Thus began Pradhan’s life as a ‘bhonti’, one among scores...

Kareena Pradhan* was 11 when her parents — labourers at a tea garden in India’s north-eastern state of Assam — sold her to a trafficker for Rs 2,000. Her buyer then sold her to a family in Arunachal Pradesh, a hill state that borders China and Myanmar in the extreme northeastern part of India, to do household chores. Thus began Pradhan’s life as a ‘bhonti’, one among scores of Assam’s vulnerable children who are illicitly sold into domestic slavery in Arunachal Pradesh.

Those who live in the predominantly tribal state are well aware of the ‘bhonti culture’. In Assamese, bhonti is an endearing term for a younger sister. But in Arunachal Pradesh, it refers to a female domestic worker, almost always a minor. They are called ‘bhontis’ as most of the domestic workers hail from Assam and its impoverished tea belt as well as the violence-affected Bodo tribal areas.

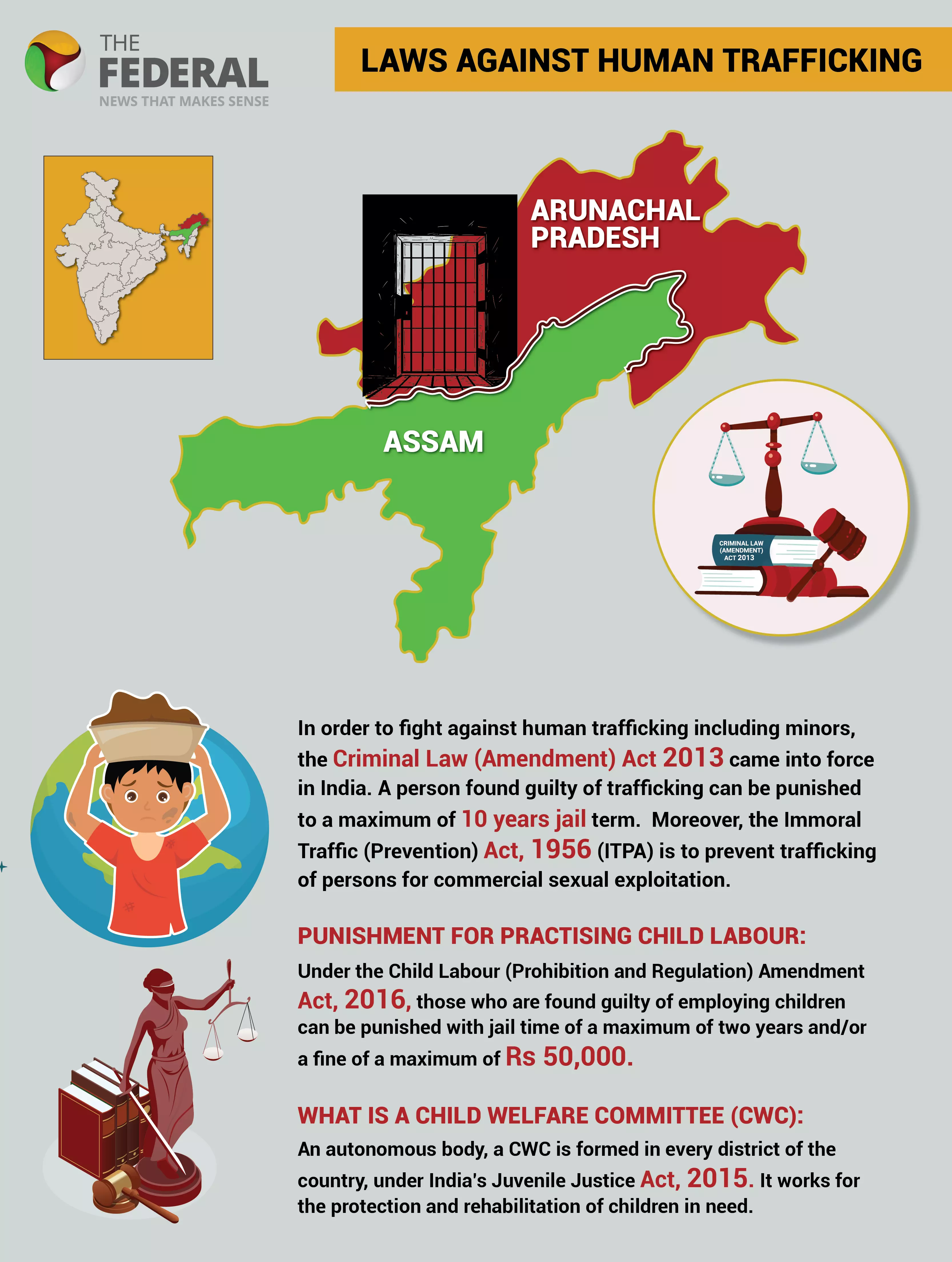

These girls cook, clean, work as farm labourers and raise infants like a nanny. “It is an undeclared custom to have a bhonti (sometimes two or three of them) working in almost every household in Arunachal Pradesh. The practice is in clear violation of various laws, including the Child Labour Act,” says Racho Buda, chairperson of the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) of Arunachal Pradesh’s Lower Subansiri district. “Unfortunately, people don’t seem to acknowledge the problem and continue hiring them, some even treating these minors like slaves,” he adds.

Sonia Rajbongshi (name changed), 12, who grew up in Assam's Beesakopie tea estate was trafficked to Arunachal Pradesh's Bomdila this year. She was working as a domestic help before she was rescued by the Assam Police.

Engaging minors in work is prohibited under the Indian law of Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986. However, the geographical location helps traffickers sneak in minor girls from Assam to Arunachal Pradesh, which share a border of 800km, without much difficulty. Girls often below 14 years of age (some as young as six years old) are being trafficked for Rs 2,000-Rs 5,000. Some parents give them up for “adoption”, but without any paperwork. These children are seen working everywhere — from paddy fields to private and government residences, including that of top elected representatives. According to media reports, they are subjected to backbreaking work and unimaginable physical torture, including rape.

***

The September heat in Naharlagun can be cruel. The town, a suburb of the state capital Itanagar, this year witnessed an extended summer beyond the usual August. Dust released from the ongoing construction works in the town adds to the humidity to make life difficult.

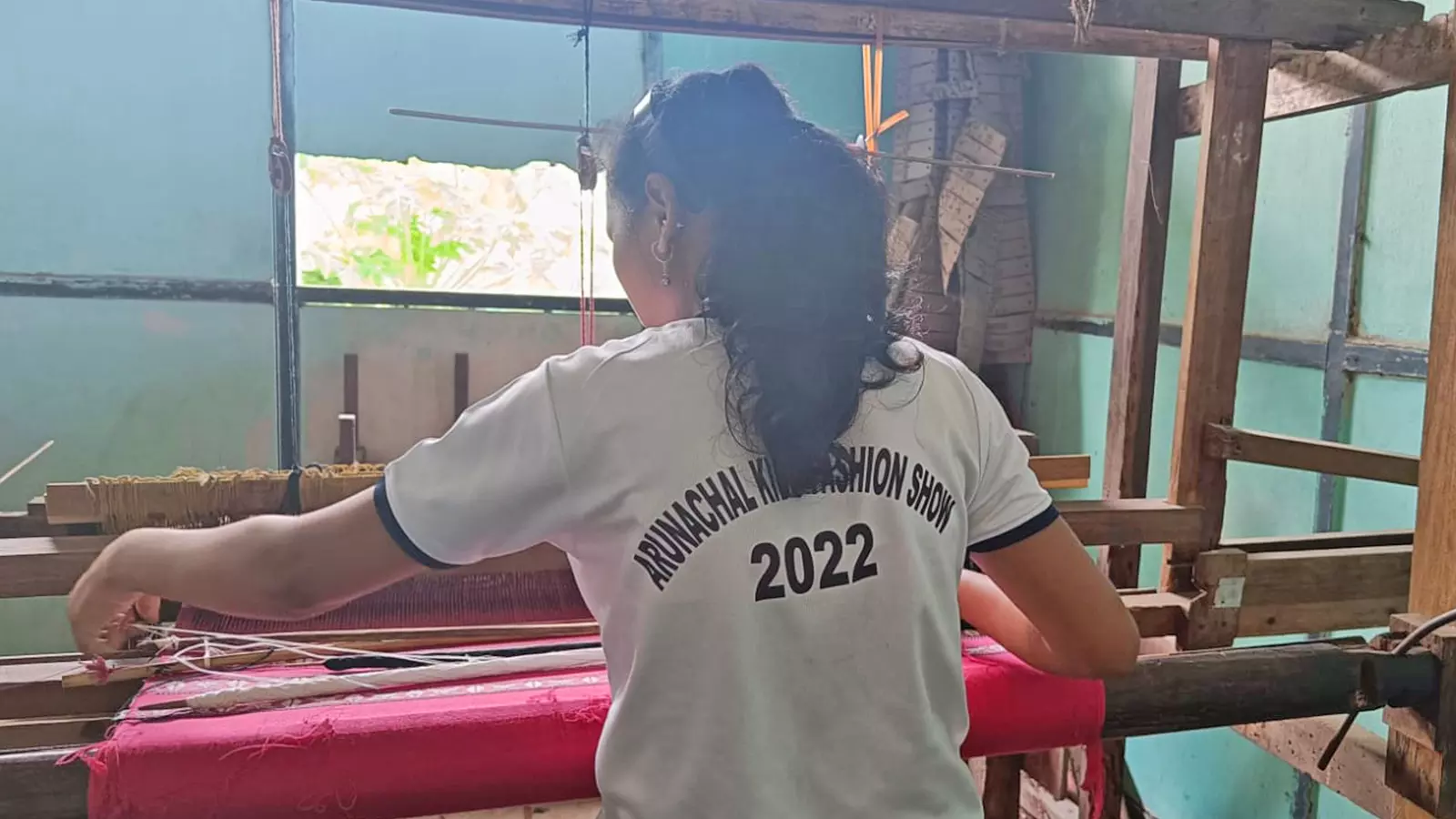

But unaffected by the discomfort, Pradhan devotedly worked at a loom when this reporter met her at a weaving centre in Naharlagun. Pradhan, who turned 18 recently, was learning to weave a galey (a traditional garment worn by women in Arunachal Pradesh). She no longer works as a bhonti and is now trying to cobble up a new life and identity for herself with the help of a non-profit organisation. But to reach here, Pradhan has endured immeasurable humiliation and torture, including sexual violence.

Pradhan belongs to a tea tribe or Adivasi community from the Mazbat tea garden in Udalguri, part of Assam’s Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR). She says her parents, tea garden labourers, sold her to a trafficker in 2016 “because they were very poor and had barely enough to eat”. “They are still very poor,” she says, without any feeling of resentment or attachment in her voice.

“I still remember the day I left my home. My buyer, a total stranger to me, sensing that I was scared, gave me some snacks and sweets as we boarded a bus. By late evening, I was in Itanagar. He handed me over to my ‘employer’ at his house. In return, he got a bundle of currency notes,” she adds.

For four years, Pradhan faced physical and sexual abuse at her employer’s house. “I was not just slapped and kicked frequently for little mistakes, but also molested by the male members of the family,” she says. In 2020, she ran away from her employer’s place to escape the daily brutality.

The police found her roaming aimlessly in Naharlagun. After being presented to the CWC members of the Papum Pare district, she was sent to stay at a child care institution (CCI) run by Oju Welfare Association (OWA), an NGO, in Naharlagun.

Around 95 km to the east of Naharlagun lies the town of Ziro. When this reporter visited the town during the second week of September, the weather was pleasant, and the residents were gearing up to host the popular annual music festival. A huge ground surrounded by paddy fields was to host the Ziro Music Festival at the end of the month. Behind the fields were bamboo huts built by the indigenous Apatani tribal people. In these and the concrete buildings, haphazardly mushrooming in an otherwise peaceful town, bhontis are found hard at work.

Tailyang Shanti, who runs Mother's Home —a CCI —fondly remembers ‘Lakshmi’. Officials brought the then 12-year-old destitute to Mother’s Home in April 2022.

Poverty makes Chakma children of Aranyapur village in Arunachal Pradesh's Changlang district vulnerable to trafficking.

“Lakshmi was not her real name. She, too, does not know her name. There was no document to prove her identity. She told me she was called ‘bhonti’. I realised she was working as a domestic help and had escaped her employer’s place. We started calling her Lakshmi,” said the 59-year-old social activist. “She was sweet and a little naughty. She would be running around everywhere. But that is how a child behaves.”

Over the course of more than a year and after a series of counselling, Lakshmi finally recalled her home address. In August this year, ‘Lakshmi’, now 13, was finally reunited with her family in Assam's Biswanath district after CWC officials took her home.

Since 2005, 72 children have stayed at Mother's Home. “I took care of several children. Most of them were Adivasis from Assam. They were brought to work in homes. Some of these children went through horrible experiences of physical violence. Sometimes, I miss them, but I am glad they are reunited with their families,” said Shanti.

When asked if any employer or trafficker has been punished for engaging minors in work, CWC chairperson Buda said, “None during my tenure (which started in 2021 and will end in 2024). If we start taking action against child labour then we have to arrest people from every house in Ziro. It will be a chaotic situation. The tribal people despite having college education are often unaware of laws against child labour and human trafficking. We conduct awareness programmes and educate people to dissuade them from hiring minors.”

In the last two years, the CWC Lower Subansiri district has registered 20 cases. Out of these, 14 are related to ‘runaway children’. These runaway children were rescued from the streets and are “suspected” to be former child labourers.

Mother's Home in Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh.

“Engaging minor female household help is widely prevalent in Arunachal Pradesh. In most instances, the girls are trafficked from Assam,” said Sunil Mow, an advocate and anti-human trafficking activist. Human trafficking is prohibited under Article 23 (1) of the Indian Constitution.

Trafficking of minors from Assam to Arunachal Pradesh was the focus of this investigative reporting done over a period of 10 months, beginning December 2022. During the period, this reporter spoke to 20 victims/survivors of human trafficking and met families of 15 children who were either missing or dead after they went to work in different parts of Arunachal Pradesh. The interviews were conducted in Assam's Kokrajhar, Chirang, Tinsukia and Kamrup districts and Arunachal Pradesh's Papum Pare (Itanagar falls under it), Lower Subansiri and Changlang districts.

The childcare institution, which became Pradhan’s refuge, at present hosts 60 children — mostly belonging to Assam’s tea tribe community. “Some of them are former child labourers and the others are runaways. They were rescued by the police and will be staying with us till they are reunited with their families. In the meantime, they are attending the school run by our NGO,” said Jangphun Tangjang, superintendent of the CCI.

The tea gardens’ curse

Almost 300 km from Naharlagun at the Beesakopie Tea Estate in Assam’s Tinsukia district, this reporter met Sonia Rajbongshi* (12) and Antara Tanti* (11). They live in one of the labour colonies built within the vast estate. Both the Adivasi girls were trafficked one year apart to Bomdila in Arunachal Pradesh's West Kameng district.

In 2022, Tanti's mother, a tea garden worker, sold her to a trafficker for Rs 2,000. Like Pradhan, Tanti was resold by the trafficker to a government official’s family in Bomdila. The 11-year-old was regularly beaten by family members of her employer for the slightest mistake. “Muk bahut marisil (They used to beat me a lot),” she said.

A view of a tea garden in Assam. The verdant tea plantations, located in the upper region and Nothern Brahmaputra belt of Assam, have become trafficking hubs.

After a local NGO Purva Bharati Educational Trust (PBET), which works for the education of girl children, came to know that Tanti was absent from school for a long period, they asked her mother to bring her back home. “My employer agreed to send me back following my mother’s plea,” said Tanti.

The same trafficker who sold Tanti took Rajbongshi to Bomdila this year under the pretext of a vacation and sold her to a family there, said her father Ramesh Rajbongshi*, a carpenter. This ‘agent’ was a person known to everyone in the neighbourhood.

“Usually an agent is a familiar face who roams around in vulnerable areas to coax parents of girls to send them to Arunachal Pradesh,” said D Savio Lakra, programme manager, State Child Protection Society Assam under the Directorate of Women and Child Development, Assam.

Ramesh Rajbongshi said they know him as Honey Ali. “Now he is absconding, and the police are searching for him,” he said.

The 12-year-old was rescued by a team of Assam Police after she borrowed a phone from an Adivasi labourer working in Bomdila and called her father.

“The Adivasi man was working as a labourer at a construction site near my employer’s home. After I told him I wanted to go home, he gave me his phone,” said Rajbongshi.

The minor was presented before the CWC and stayed for a day in a shelter home before being reunited with her family. “Both these girls are reeling under the trauma of being forced to work and subjected to physical violence. They are not yet ready to go back to school,” said Amrita Pradhani, an activist, who works with PBET.

Purudhan Chakma (50) and his wife Liduvi Chakma (45) from Arunachal Pradesh's Changlang district hold the picture of their missing son.

The verdant tea plantations, located in the upper region and northern Brahmaputra belt of Assam, have become trafficking hubs. The same gardens that produce world-famous tea are filled with workers, who hail from Adivasi or tea tribe communities, and suffer from unimaginable poverty and lack of development.

“Girls from these poor families are usually trafficked,” said Assam-based activist Digambar Narzary, who works for the rescue and rehabilitation of trafficking victims.

Assam’s char areas (sandbars), where poor Bengali-speaking Muslims reside, are another favourite hunting ground for traffickers.

“Despite the crime happening next door (referring to the close proximity between the two states), there is a silence around the whole horrific abuse of children. The practice has been going on forever and politicians and bureaucrats from both states choose to ignore it. Sometimes, they are part of the problem,” said Narzary.

With rising population and affluence, the demand for ‘bhontis’ has also risen exponentially in the households of Arunachal Pradesh with traffickers now spreading their tentacles to impoverished areas within the state.

Intra-state trafficking

Diyun in Arunachal Pradesh’s Changlang district, located 240km west towards Itanagar, is one of the new hunting grounds for traffickers. Here, this reporter met family members of minors who are working in different parts of the hill state. Some of them are "dead or missing".

Diyun is a settlement of Chakmas--mostly Buddhists--who came to Arunachal Pradesh in the 1960s from the Chittagong Hill Tracts of former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The state is home to around 65,000 Chakma people — many of them refugees. At least 35,000 of them stay in Diyun and its surrounding villages.

These villages are one of the most poverty-stricken parts of Arunachal Pradesh. “Poverty is the main reason for Chakma people to send their children to work,” said Bedana Chakma, CWC member, Changlang district.

A view of a paddy field in Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. Bhontis also work as farm labourers.

Eight years ago, Purudhan Chakma (50) and his wife Liduvi Chakma (45) from Aranyapur village sent their eldest son, then 12 years old, to work in a home in Diyun. They were paid Rs 12,000 by the employer. “Later the employer took my son to Itanagar. Since then he has been missing. We have tried to file a case against the employer but the police dissuaded us. We have lost all contact with the employer. The last time we spoke over the phone he told us our son was not with him anymore,” alleged the mother.

Phaneswar Chakma (58) is a widow from Aranyapur village. In 2021, she sent her daughter to work in Pasighat, the headquarters of East Siang district in Arunachal Pradesh. Her daughter, then 15 years old, died by suicide at her employer’s place within a month of her joining. “I went to Pasighat and brought back her body. I was told in Pasighat that a post-mortem was done on her, which confirmed suicide. Before her funeral here, we realised the post-mortem was not done. I doubt foul play behind her death. She would never have died by suicide,” Chakma said. The 58-year-old wants justice for her daughter. “But I am a poor widow and have no means to pursue a case against the employer.”

“Child labour has been normalised in Arunachal Pradesh to the extent that all such violence against minors is unreported," said Arunjit Chakma, an activist from Changlang district, who is working with many of these victim families.

Numbers don't reveal the reality

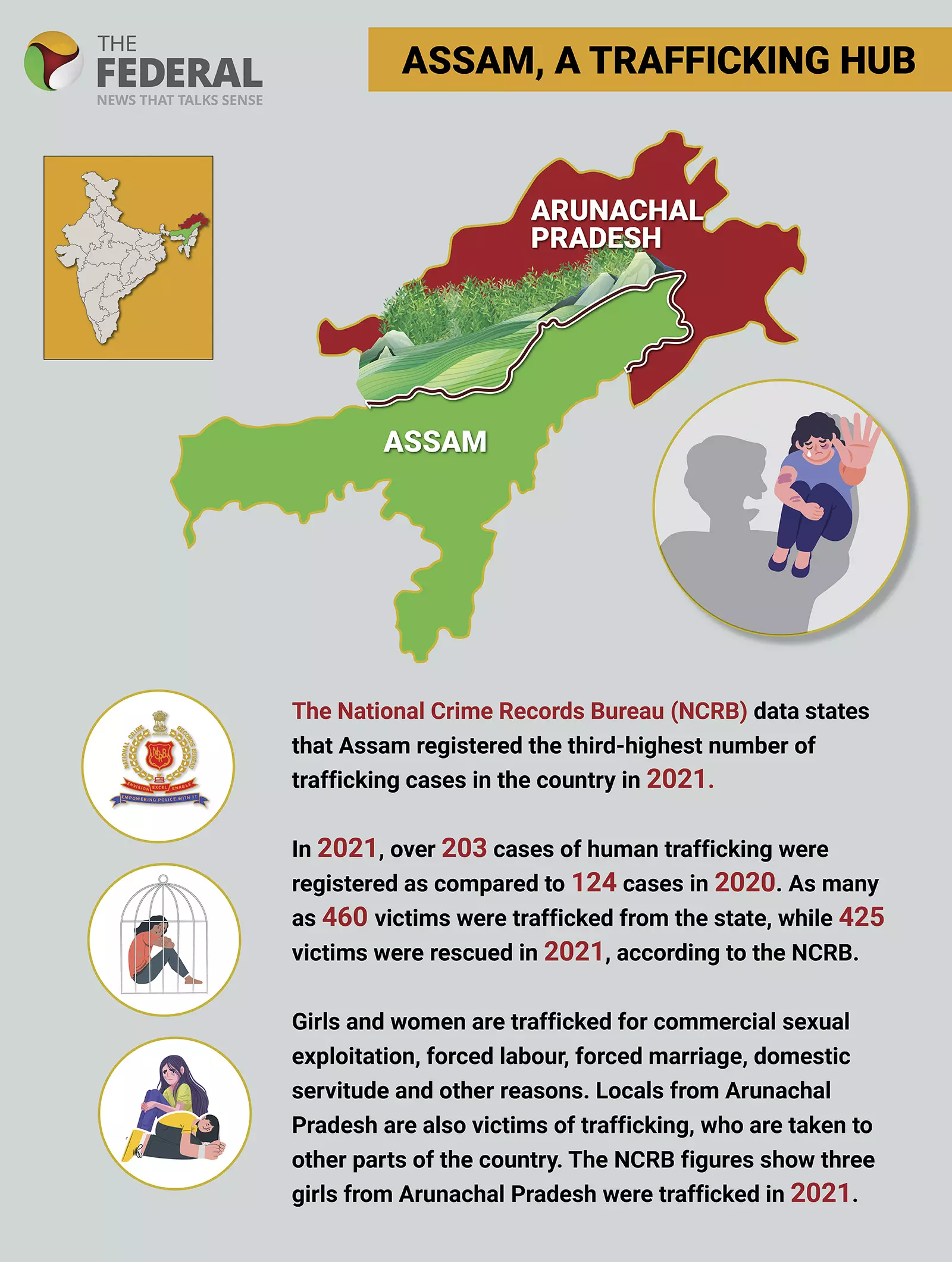

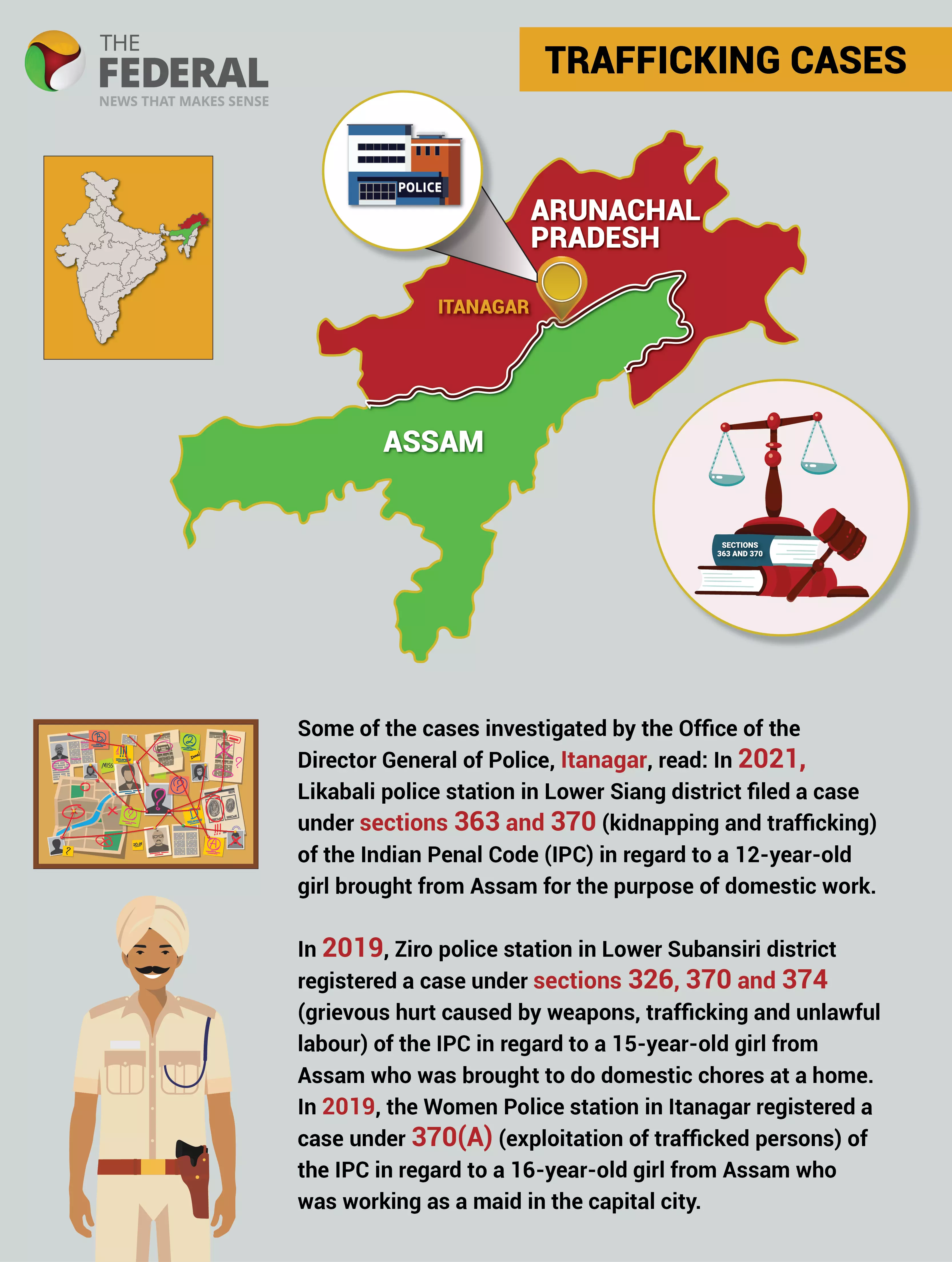

The data shared by the Office of the Director General of Police, Itanagar, shows 14 cases of human trafficking were registered in Arunachal Pradesh from 2019 to September 2023. The FIRs filed in these cases resulted in the rescue of 22 victims and the arrest of 21 traffickers.

Usually, cases are not registered against employers because parents are reluctant to do so. The cops say it is difficult to arrest traffickers as the “whole business” is a well-oiled machinery with parents and employers also being part of it.

“The registered cases are just the tip of an iceberg. Mostly they go unreported as parents of minors, traffickers and employers are involved in the crime. Sometimes, trafficking cases get registered under kidnapping or POCSO and the guilty are punished accordingly,” said Jummar Basar, Superintendent of Police (Crime) and nodal officer of the Anti-Human Trafficking Unit, Arunachal Pradesh. POCSO is Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012.

By the Assam government’s own admission in the Legislative Assembly in March this year, at least 481 children were trafficked between 2017 and 2022. Moreover, 759 children have gone missing since 2017. At least, 666 of them were rescued.

Last year in December, this reporter spoke to six survivors of human trafficking in Kokrajhar, part of Assam’s BTR. Anjali Daimary*, 19, a Bodo girl, worked as a domestic help in a household in Itanagar for several years. In 2019, when Daimary was 15, she was put on a bus by her employer to Assam. She was seven months pregnant. The girl was allegedly raped by one of the male family members where she was working.

She was found at a bus stop by activists working to prevent human trafficking in Kokrajhar. Two months later, she gave birth to a child at a shelter home as her family refused to take her back. Daimary said she gave up her child for adoption as she was too young to raise a baby.

A grey area

Although not openly criticised, several empathetic voices within the border state of Arunachal Pradesh want an end to the ugly ‘bhonti culture’. They feel it is a blot on their beautiful land endowed with picturesque mountains and rivers. Within these voices are people who caution not to read the whole issue in "black and white".

While poverty drives parents to send their children to Arunachal Pradesh, the labour force is in shortage in the hill state. But that cannot be a justification for employing minors.

“There is no doubt child labour should end. Crime against minors is despicable. However, not all employers are monsters. A lot of them take good care of the girls and treat them as their family members. Many of these girls go to school. In a way, these girls are saved from abject poverty,” Ngurang Achung, a former member of the Arunachal Pradesh State Commission for the Protection of Child Rights, said.

Tailyang Shanti, who runs Mothers Home in Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh, has taken care of several rescued Adivasi children from Assam.

Between 2020 and 2022, 130 cases were reported to the Commission. Out of it, five cases were of trafficking, 11 child labour, one bonded labour, 69 POCSO and four physical assaults.

“The whole racket is run from Assam as traffickers call people in Arunachal Pradesh to 'sell' domestic help. These agents take exorbitant money from the employers. Sometimes, these girls run away with the help of traffickers. These same runaway girls could be seen working in another house in a few weeks’ time,” Keni Bagra, Superintendent of Police, Lower Subansiri, said.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

Earlier this year, Pradhan went back to her home in Assam for the first time in seven years. The 18-year-old sounds indifferent about the reunion, though. “I could not stay more than three weeks at my home. I contacted OWA and they agreed to take me back.”“It is not easy for survivors of trafficking to go back home and lead a normal life. There are chances of them being re-trafficked. There is no one formula for rehabilitation of the survivors,” said Arunachal Pradesh Women Welfare Society president Kani Nada Maling.

Pradhan aspires to be a fashion designer. The back of her white T-shirt read, “Arunachal Fashion Show 2022”, a window to her ambition. “Oh, the T-shirt is a gift,” she smiled. “I can't afford to attend a fashion show but one day I will after I become a fashion designer.”

(*Names of all survivors have been changed to protect their identity)

(This reporting by a contributor is supported by a grant from Journalism Centre on Global Trafficking.)