- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Beyond apocalypse: As COP29 goes on, how climate fiction showcases our relationship with Earth

If you think about it, the apocalypse has always been our favourite bedtime story, an end-of-the-world lullaby that reassures us with a simple narrative arc: the world starts, something goes terribly wrong, and the world ends, usually with a spectacular bang or an attack by the aliens. But climate fiction — or ‘cli-fi,’ as it has come to be known — has changed this storyline. The...

If you think about it, the apocalypse has always been our favourite bedtime story, an end-of-the-world lullaby that reassures us with a simple narrative arc: the world starts, something goes terribly wrong, and the world ends, usually with a spectacular bang or an attack by the aliens. But climate fiction — or ‘cli-fi,’ as it has come to be known — has changed this storyline. The genre reveals to us the price of human choices, and the all-too-real spectre of an Earth in crisis.

Unlike the science fiction (or sci-fi) of yesteryear, in which technology either saved or doomed us in a flash of futuristic glamour, cli-fi holds up a magnifying glass to the world we’re already living in, where the apocalypse isn’t some distant, theoretical event but an ongoing process. This isn’t the realm of escapist fantasies or neatly plotted dystopias — climate fiction roots itself firmly in the here and now (most of them, anyway), turning our collective anxieties into stories that engage, unsettle, and provoke.

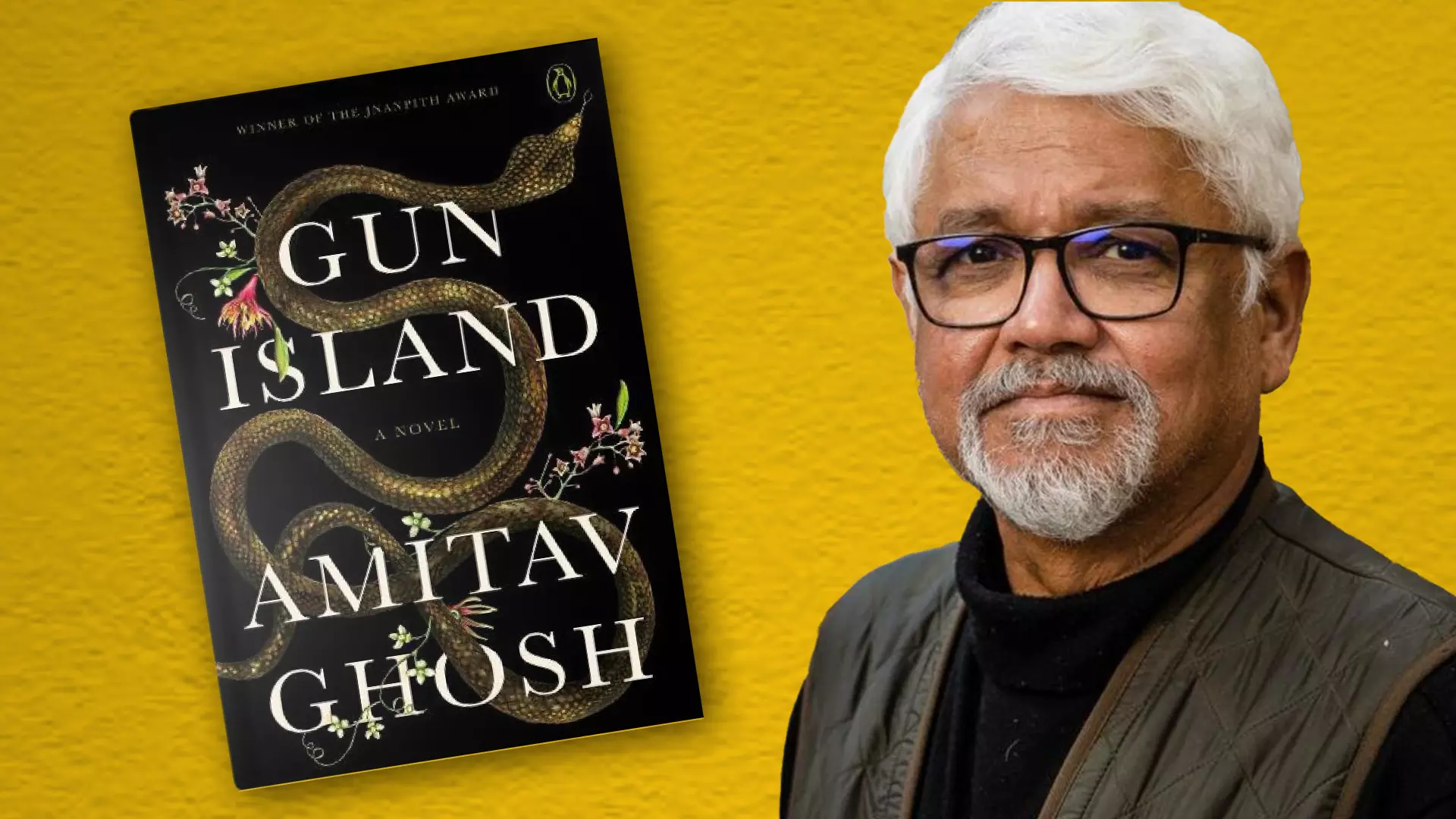

Take Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island (Penguin Random House, 2019), a novel that dares to straddle both the mythic and the deeply contemporary. Ghosh’s novel traces the journey of Deen Datta, an Indian rare-book dealer, whose seemingly academic interest in a centuries-old Bengali legend drags him into the swirling waters of climate change and human displacement. The legend tells of a cursed island guarded by the goddess Manasa, but as the story unravels, Ghosh makes it clear that curses, in our world, take the shape of rising sea levels and erratic weather patterns.

Amitav Ghosh’s 'Gun Island' traces the journey of Deen Datta, whose seemingly academic interest in a centuries-old Bengali legend drags him into the swirling waters of climate change and human displacement.

Gun Island, a cautionary tale, is also a meditation on the ways past myths and present realities, the supernatural and the hyperreal meet. As Deen travels from Venice to the Sundarbans, witnessing firsthand the environmental havoc that forces human migration, Ghosh asks us to consider how climate change isn’t just a matter of melting ice caps and endangered species but a deeply human crisis. The novel, like a Venetian mask party, is steeped in transitions and shifting identities, only to reveal that the greatest threat of all is woven into the very fabric of our world.

Gun Island, on one hand, reads like a thriller that keeps you turning the pages, breathless with the urgency of its unfolding mystery. But beneath that, it’s a philosophical inquiry, an interrogation of human complicity in climate disaster. And, as its jackets will tell you: “Also a story of hope, of a man whose faith in the world and the future is restored by two remarkable women.” It dares to wonder: How long can we pretend that the world will continue to turn, undisturbed, as the waters rise?

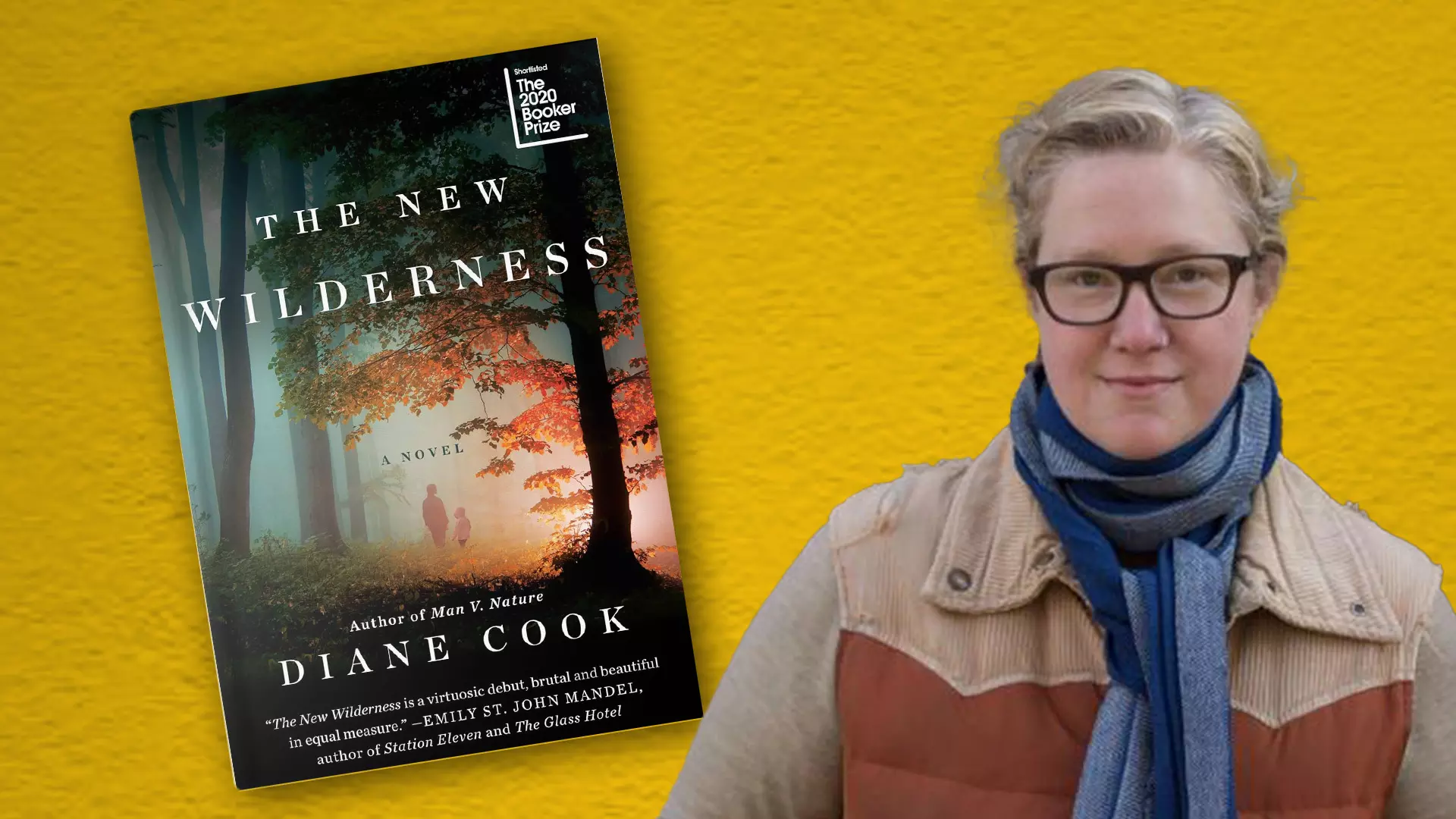

While Ghosh spins his tale with folklore and somewhat academic quests of its protagonist, Diane Cook’s The New Wilderness (HarperCollins, 2020), shortlisted for the Booker Prize, takes us to a post-apocalyptic world, in which the last unpolluted stretch of wilderness becomes a refuge — and a test ground — for a select group of human beings, who must learn to live off the land or perish. At the centre of this brutal, vividly imagined landscape is Bea, a mother who joins the wilderness experiment to save her ailing daughter, five-year-old Agnes.

Diane Cook’s 'The New Wilderness' takes us to a post-apocalyptic world.

Cook’s prose is as wild and unrestrained as the landscape she conjures, full of sharp edges and primal fears. “Diane Cook upends old tropes of autonomy, survival, and civilization to reveal startling new life teeming beneath, giving a glimpse into the ways the world we think we know could come unstuck and come to life in the care of the women and girls of the future. This is not just a thrilling, curious, vibrant book, but an essential one, a compass to guide us into the future,” wrote Alexandra Kleeman, author of You Too Can Have A Body Like Mine, in her review of Cook’s debut novel, widely hailed as ‘the great climate change novel of our time’.

I found The New Wilderness utterly powerful especially when it comes to the kind of questions it raises about what it means to be human in such a world. Are we capable of change, or is our destructive nature an inescapable part of us? The novel doesn’t offer easy answers, which, in fact, makes it all the more haunting. Cook’s isn’t a book that tiptoes around the climate crisis; it plunges you into a world where survival hinges on rediscovering a lost symbiosis with nature.

The wilderness, in the novel, itself becomes a character, capricious and unforgiving, a reminder of what we’ve lost in our quest for modern convenience. “Our basest actions that show our desires and needs, our cunning, simple joys, loyalty, love, unnamable grief, it all activates so much of our lives and so many of these behaviours are universal. Being able to remember how much we share with the natural world makes the business of being human a little less bewildering, and lonely,” Cook said in an interview to the Booker Prize Foundation.

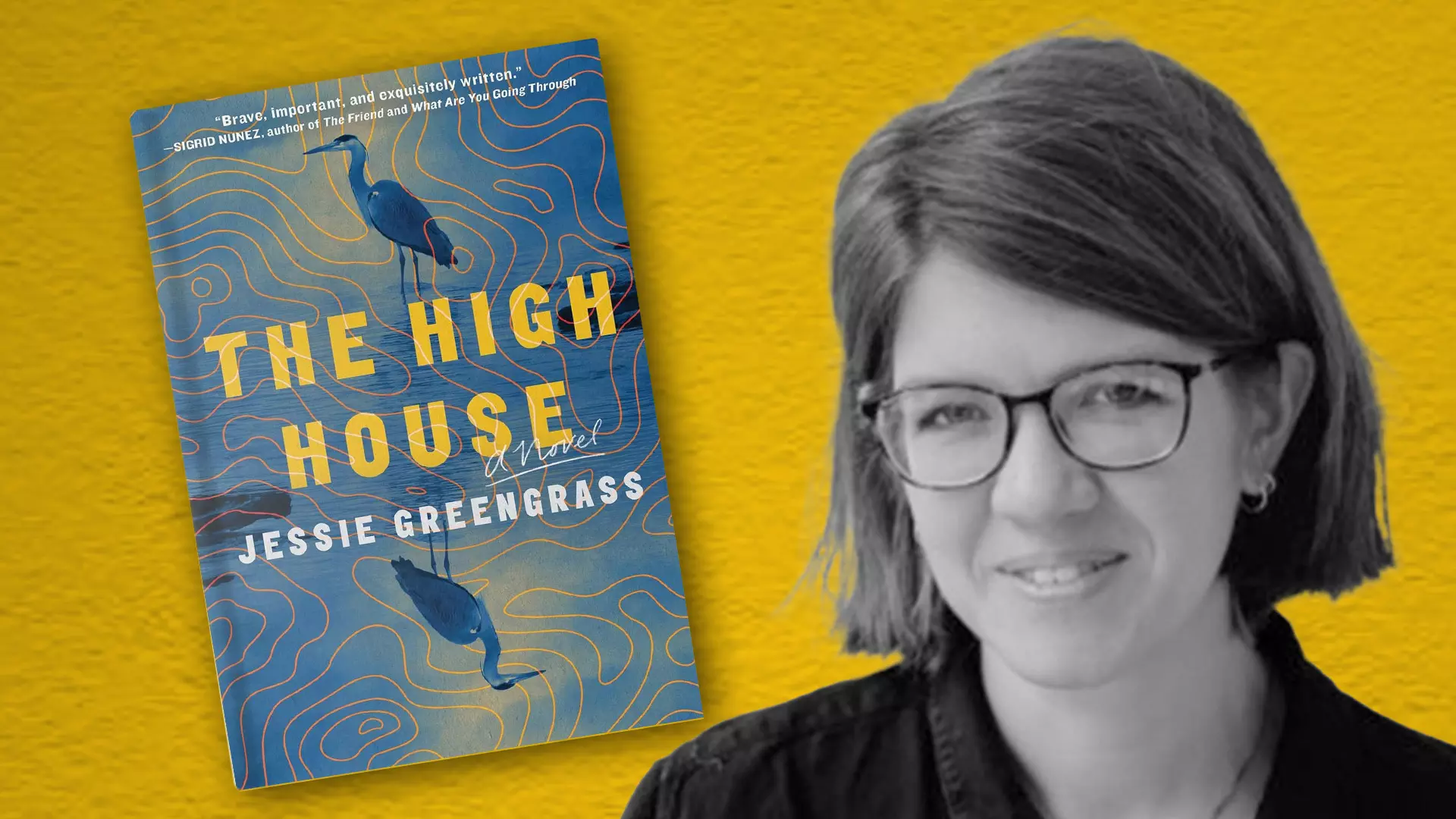

Moving from the wild to the domestic, Jessie Greengrass’s The High House (Simon & Schuster, 2021), shortlisted for the Costa Award, shows that climate catastrophe doesn’t just happen in the abstract or the extreme; it infiltrates our homes, our most sacred spaces. The novel centres on a small family of four — Caro and her younger half-brother Pauly, and Grandy (a former village caretaker) and his granddaughter Sally — who retreats to a house on a hill as rising waters threaten to drown the world. But this isn’t a dramatic, last-stand sort of story. Instead, it’s a quiet, elegiac exploration of what it means to prepare for a future that no longer resembles the past.

Jessie Greengrass’s 'The High House' shows that climate catastrophe doesn’t just happen in the abstract or the extreme; it infiltrates our homes, our most sacred spaces.

Greengrass’s prose is infused with a sense of melancholy, capturing the love, sacrifice, and heartache of a family facing an inevitable end. She writes about parenthood and responsibility with a tenderness that breaks your heart and then asks you to keep reading, to keep feeling. There’s an almost unbearable tension in the way Greengrass describes simple domestic scenes — cooking a meal, caring for a child, watching the weather — that take on monumental significance in the shadow of the climate crisis. It shows how the choices we make every day, the small acts of care that might, in the end, are the only thing that matters.

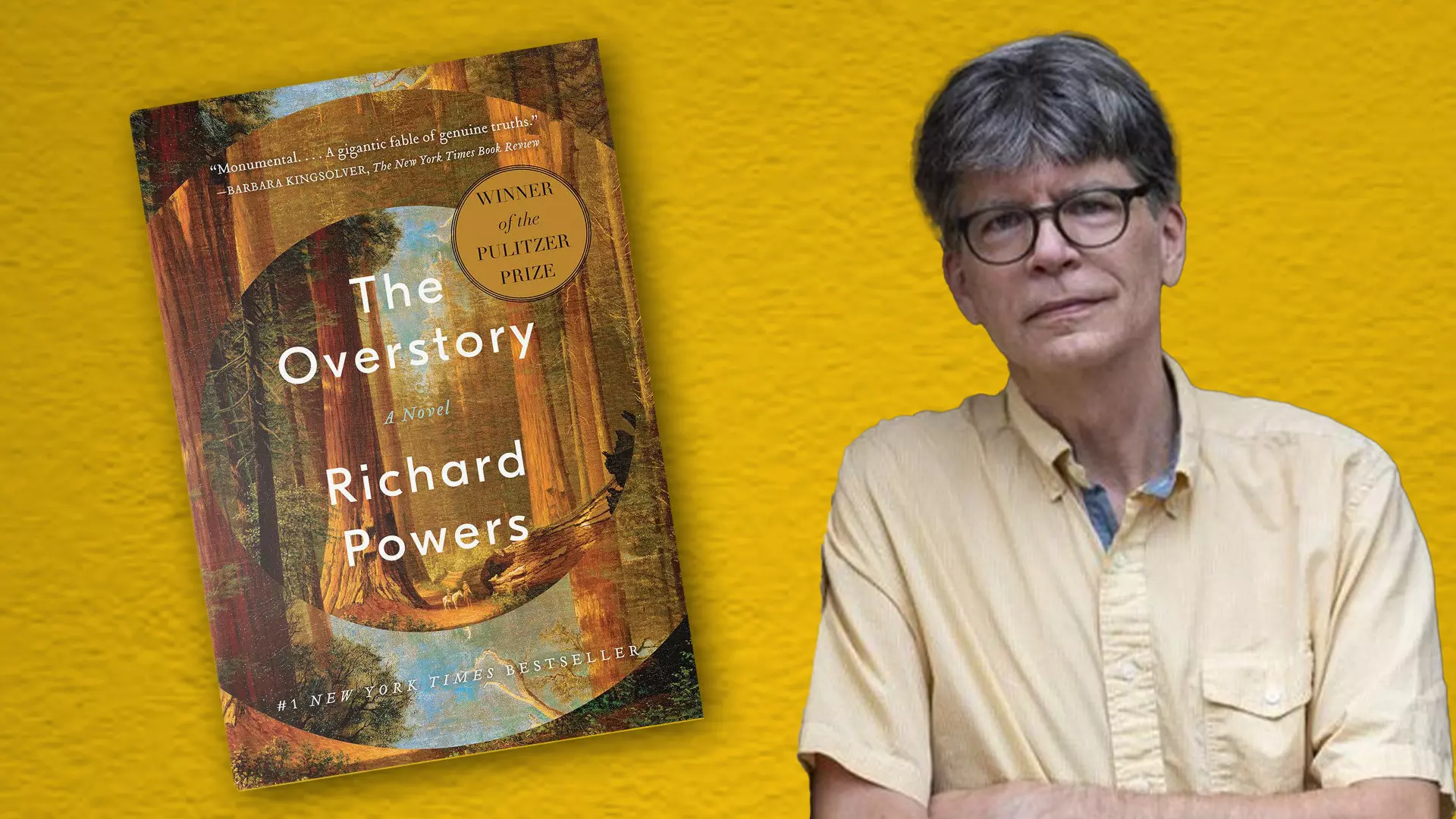

Another recent novel that redefines how we perceive the natural world and our relationship with it is Richard Powers’ The Overstory (Penguin Random House, 2018), winner of the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. A sprawling, ambitious, and deeply affecting novel, it weaves together the stories of nine diverse Americans whose lives are forever changed through their encounters with trees. These encounters aren’t mere happenstances but pivotal, often transformative experiences that open their eyes to the intelligence, interconnectedness, and majesty of the arboreal world.

Richard Powers’ 'The Overstory' is winner of the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Powers structures the novel like a tree itself, with sections named “Roots,” “Trunk,” “Crown,” and “Seeds,” echoing the life cycle of forests and showcasing how interconnected stories grow from deep, invisible foundations. The novel delves into each character’s background, detailing how their connection to trees shapes their identities. For example, Nicholas Hoel inherits a multi-generational tradition of photographing a chestnut tree on his family’s Iowa farm. Mimi Ma, the daughter of a Chinese immigrant, clings to memories of a mulberry tree that served as a source of comfort and heritage. Patricia Westerford, a scientist who uncovers groundbreaking truths about how trees communicate, dedicates her life to advocating for their preservation, even in the face of professional ruin.

Soon, these characters’ paths begin to intertwine in unexpected and poignant ways, propelled by their growing realisation of the environmental crisis threatening the planet. Powers explores the characters’ responses to deforestation and climate change, some of which become acts of defiance and activism. One of the novel’s most compelling arcs follows Olivia Vandergriff, a college dropout who has a near-death experience and emerges with a vision that compels her to become an eco-warrior. Her spiritual awakening drives her to join a radical environmental group, and her path crosses with those of other characters as they engage in civil disobedience to protect old-growth forests from destruction.

Powers draws readers into a world where trees are not silent backdrops but sentient beings with wisdom and memory. His descriptions of the natural world are lush and evocative, illustrating how trees communicate, form alliances, and bear witness to centuries of human activity. By grounding his narrative in ecological science, Powers challenges us to reevaluate our destructive impact on the planet and ponder whether hope lies in recognising the interconnectedness of all living things.

What unites these diverse novels is a shared sense of urgency and a refusal to let readers look away from the climate catastrophe. But beyond the alarm bells, cli-fi offers something deeper: a chance to imagine new ways of living, of relating to the world and each other. It suggests that while we may be facing unprecedented challenges, we are also capable of unprecedented empathy. These novels do not just depict the end of the world as we know it, it pushes us to consider how we might rebuild, how we might learn from our mistakes. They offer us a mirror and a map — a way to prepare ourselves for the uncertain future that awaits us all.