- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

They referred to the people speaking Belare and identified them as cane splitters.About three months ago, 80-year-old Sidda Belare died. What also died with Sidda is the language he spoke as the octogenarian was the last man to fluently speak Dravidian tribal language Belare.Tribal languages have increasingly died leaving not a trace behind. The phenomenon was also experienced in the death of...

They referred to the people speaking Belare and identified them as cane splitters.About three months ago, 80-year-old Sidda Belare died. What also died with Sidda is the language he spoke as the octogenarian was the last man to fluently speak Dravidian tribal language Belare.

Tribal languages have increasingly died leaving not a trace behind. The phenomenon was also experienced in the death of Bo language with the demise of Boa Sr — the last person to speak the language on the Andaman Islands; and Amadeo Garcia whose death led to the death of Taushiroe, a language identified with the Amazon tribe.

Languages never die alone. What dies with them are the cultures shaped by and around languages. Worryingly, media reports on the death of ‘last speakers’ seldom talk about the death of the associated cultures.

Language, as poet and existentialist writer Walt Whitman said, is the sum total of all that humans experience as a species. Language is not an abstract construction of the learned, or of dictionary makers, but is something arising out of the work, needs, ties, affection, and tastes of long generations of humanity and has its bases broad and low, close to the ground.

Anthropologists say when a language dies, a way of life dies, a way of thinking disappears, and a connection between two worlds — that in which the said language is spoken and that outside of it — is lost.

It is for this reason that Prof A Murigeppa and Dr Mahendra Harihara have been in the pursuit of documenting languages and the associated life around it. Both did elaborate research on Belare and its grammar as part of their study of endangered languages in south India, a project commissioned by the Central University of Karnataka. The two scholars have studied, documented and analysed 10 languages including Arebashe, Belare, Betta Kuruba, Beary, Chenchu, Erava, Havyaka, Koracha, Pattegar and Sankethi. A result of their endeavour was A Grammar of Belare published by the Central University of Karnataka in May 2020.

But working on conserving and documenting languages on the verge of extinction is never easy.

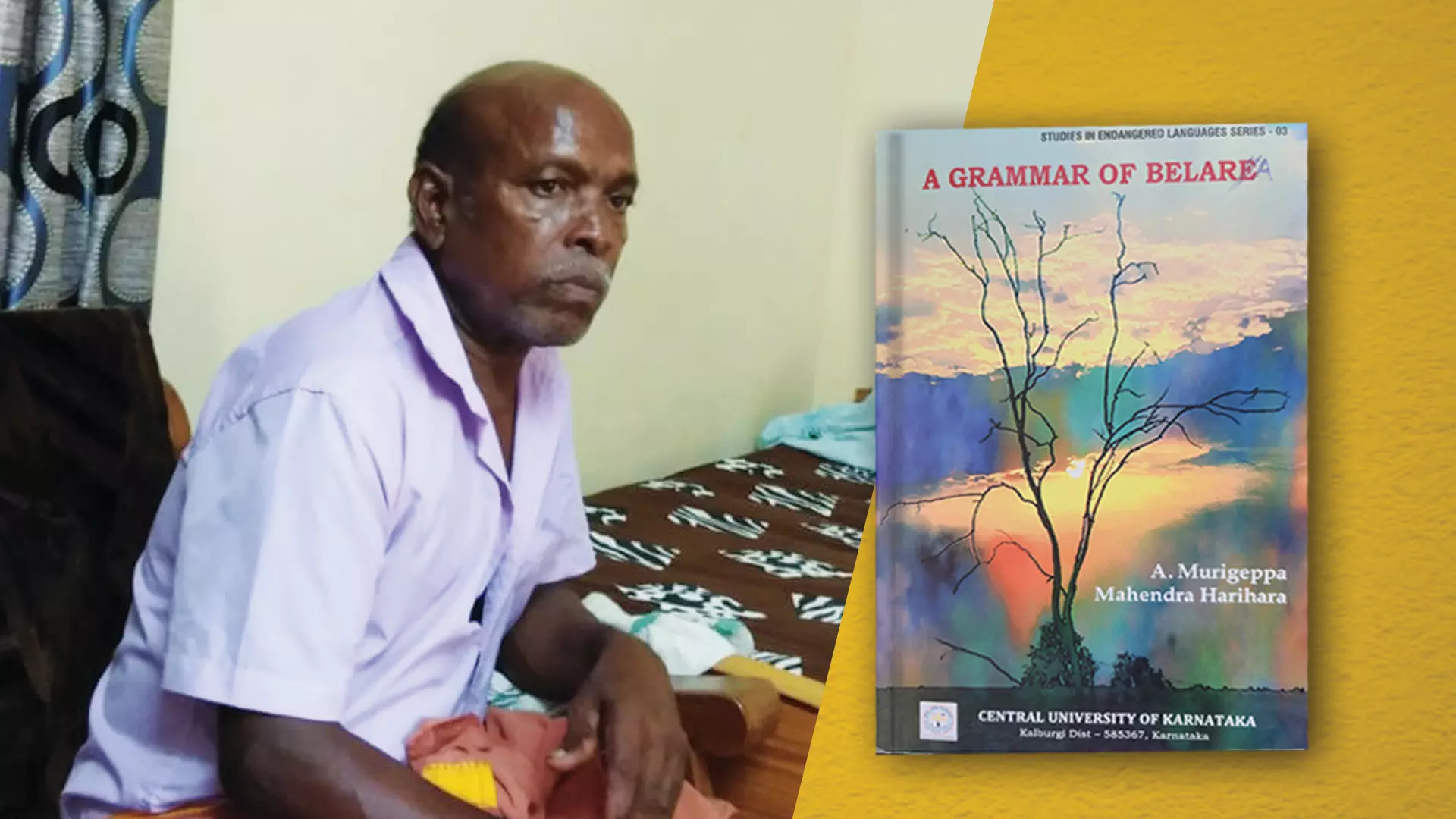

Sidda Belare with professor A Murigeppa.

“The collection of the data was very difficult because the language had been given up long back. No one in the present generation speaks Belare. They have a kind of aversion towards this speech form and they don’t want to be identified with it. We managed to find Sidda Belare, who was 75 years old then and could recollect the language to some extent. Luckily, he was also willing to share what he knew. Since the speech form ceased from usage long back, he too had mostly forgotten the language. So, he had to make efforts to recollect the speech. In the process, there is a possibility of mixing and missing some of the grammatical forms. But since the language was on the verge of extinction whatever data we collected is timely and a boon,” Murigeppa said explaining the difficulties he and his colleague faced during their research.

While not many efforts are made to preserve or document these languages, the Central University of Karnataka works to empower the endangered language communities in all possible ways by training people from among the community for sustainable development.

“I can’t thank Central University of Karnataka enough for their support in bringing out A Grammar of Belare. Though small, it is still a step towards saving the language from being forgotten for ever. At the same time the contribution of Sidda Belare which he made by sharing whatever he knew about his language is appreciable,” Murigeppa told The Federal.

According to Murigeppa, Belare is one of the tribal speech forms that has almost all the vowels and consonants the Dravidian languages have. It has 11 vowel phonemes, 22 consonant phonemes and two diphthongs.

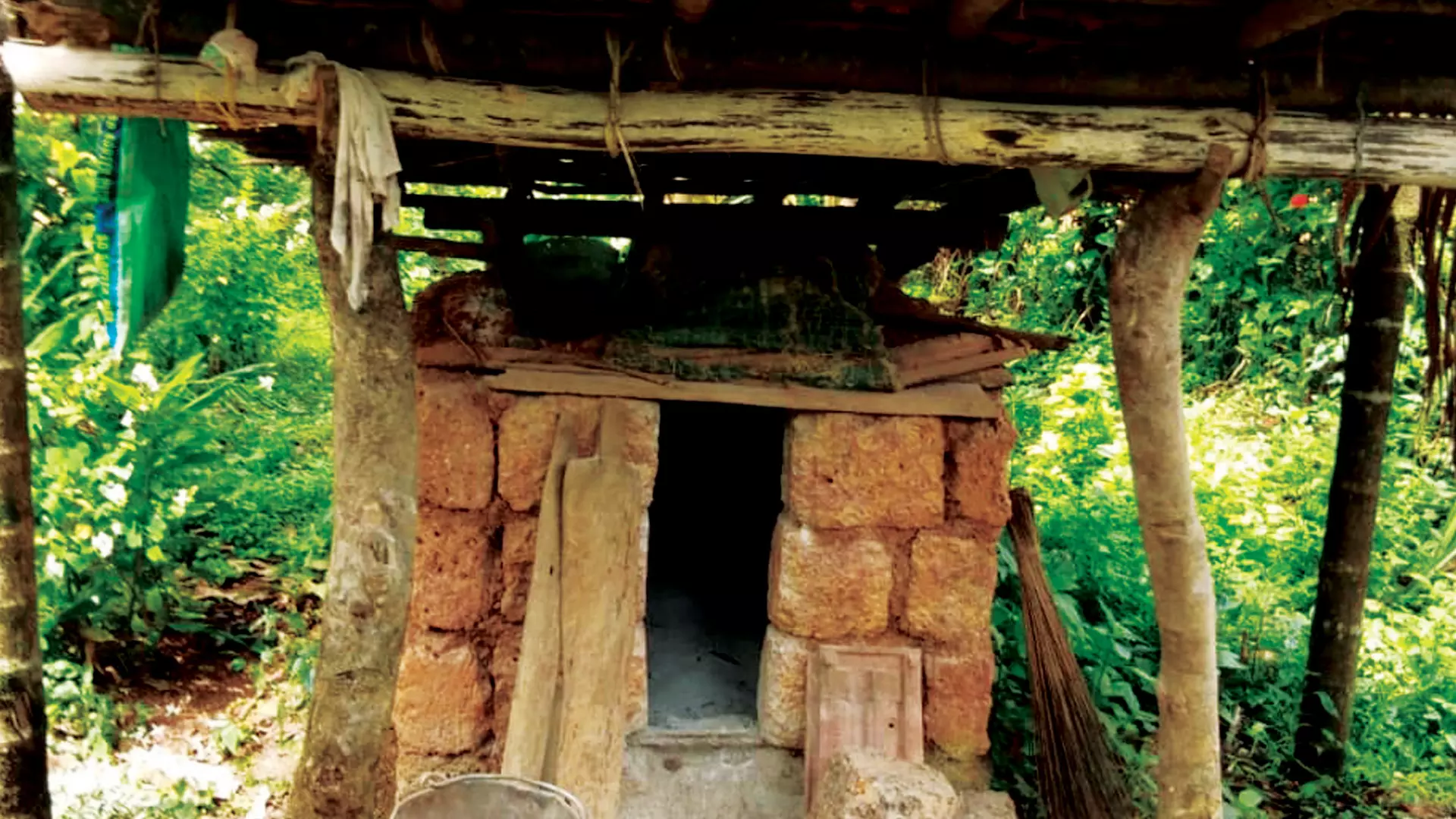

Dr DNS Bhat, who also carried out a comprehensive study of Belare and worked on the inflectional morphology of the language, the main profession of the Belara community was basket weaving. But now they have given up their traditional craft and cut soft stones for construction of houses. Dr Bhat identified the personal termination markers and tense makers in Belara and Tulu and arrived at the conclusion that the two languages have some similarities. He found the same pattern between Belara and Koraga.

Belare community

According to Prof Murigeppa, till 1890, there was no research on the culture or the speech form Belare.

The community was referred to by John Sturrock (the then district collector) in the first volume of Madras District Manuals: South Canara II in 1894, which was later recompiled by HA Stuart, a member of the Royal Statistical Society and also the member of Royal Asiatic Society in 1895. They referred to the people speaking Belare and identified them as cane splitters. In popular terms, they belong to the Medara community, who weave cane baskets. Their population according to the manual was 674 — 419 male and 255 female. Both officials included Belare speech under languages spoken in the Madras region. They have given 41 coded vocabularies in the manual.

Belare is a community of about 500 people living around Kundapura taluk of Udupi district. The settlements of the Belara community are Yedamoge, Eluru Karur, Alpadi, Mudur, Kalthodu, Aluru, Hosabalu, Rattadi, and Amasebailu. According to folk etymology, they are named as Belihari — Beli means fence in Kannada and Haru means jumping across the fence — as they are supposed to have crossed the fence and moved from there. However, the etymology of the term Belare is undecided.

The few who belong to Belare community, have occupied prominent positions in society and include advocates and engineers. Many of them became Yakshagana art exponents. “Most of them adapted to Kundapra Kannada,” says Prof Murigeppa.

Language beyond words

“Language is not only a tool for communication, but also a base for the intellectual outputs of knowledge, culture and civilisation of mankind. Due to the impact of science and technology and the process of globalisation, many of the world’s languages are on the verge of extinction. Language endangerment may lead to loss of historical and ethnic identity. India has a large number of endangered languages. In such a situation, most of the languages are unsafe, as they are faced with threats from external and internal forces. To save such languages, the fluency of the mother tongue should be improved among the speakers, especially the younger generation,” said professor HM Maheshwaraiah, renowned linguist and scholar.

Prof A Murigeppa and Dr Mahendra Harihara penned A Grammar of Belare.

Elaborating his argument, Maheshwaraiah notes, “Language endangerment or loss or death is a global phenomenon, accelerated because of the scientific and technological development and globalisation in the 21st century. Linguists, members of endangered language communities, governments, non-governmental organisations and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the European Union are actively working to save and stabilise endangered languages. The UNESCO Atlas of World’s Languages in Danger 2010 edition provides country-wise statistical data of the endangered languages of the world. Significantly, the countries including India, USA and Indonesia are on the top with the highest number of endangered languages.”

According to the People’s Linguistic Survey of India (PLSI), of the 10 endangered languages in Karnataka, eight are potentially endangered. Those languages include Soliga, Koraga, Irula, Badaga, Yerava, Gouli, Betta Kuruba and Jenu Kuruba. These languages are spoken by less than 10,000 people. Siddi and Hakki-Pikki are critically endangered as they are not spoken by the younger generation.

PLSI has published a 290-page volume on the languages of Karnataka, which records the history and culture of the language and their situation, besides the classical nature, structure and domain use of languages among other things. The Kannada version of this volume was published by Akshara Prakashana and the English version was brought out by Orient BlackSwan.

The PLSI conducted a survey of 42 languages including Kannada and minority languages such as Tulu, Konkani, Kodava, Dakhani, Sanketi and Beary. The survey also included tribal languages and languages of denotified nomadic communities such as Bhairas, Sindhi, Madigas, Hasalas Mogaveeras, Mukaris, Kunubis, Keppe Holeyas, Yanadigas, Illigas, Chunchu, Koravas, Kudiyas, Dakkalas Masteekars and Ageras and Pinjaras.

“These languages, which are spoken by fewer than 1 lakh people, face the threat of extinction, but they could be rescued through support and development,” the PLSI study report said.

Saving languages

After the 1971 Census, the Indian government stated that any indigenous language that is spoken by less than 10,000 people would no longer be considered in the list of official languages of India. With the Census counting only the languages spoken by more than 10,000 people, about 108 languages have been dropped from the list.

According to noted linguist, historian and renowned scholar Ganesh Narayan Devy — founder-director of the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre, Vadodara — India may have lost 220 languages since 1961 and another 150 languages can disappear over the next 50 years. Most dying languages, according to him, are from the indigenous tribal groups spread across the country. Prof Devy observes that there are over 600 potentially endangered languages in India and each dead language takes away a native culture.

Years ago, speaking to this writer, Jnanapith recipient writer and public intellectual UR Ananthamurthy, said that with the digital world’s influence, many tribal languages and cultures are facing the danger of becoming extinct. Interestingly, he said, “India is a country, where the illiterate speak five to seven languages, while the convent-going child speaks one.”

So how can a language that people increasingly stop speaking be saved?

Interestingly, a dictionary published recently saved a language from extinction. According to reports, Toto-a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the tribal Toto people living in parts of West Bengal recently got a dictionary. This was made possible by the efforts of a professor at the University of Calcutta. Toto Shabda Sangraha, a dictionary which was released on October 7, is compiled by Bhakta Toto, a bank-employee-cum poet.

People of the Belare community used to traditionally work as cane splitters.

Similarly, a dictionary with over 10,000 words and 1,500 idioms in use in Kundapra Kannada was published recently. Kundapra Kannada is mainly a spoken dialect but faces threats to usage from factors such as mainstream languages. Panju Gangolli, a noted cartoonist living in Mumbai, toiled for nearly two decades to come up with the first-ever dictionary of his native tongue Kundapra Kannada — a unique dialect of Kannada spoken in and around Kundapura taluk of Udupi district.

But the dialect has also seen a resurgence in recent years with the community celebrating a Kundapra Kannada day, stand-up comedy, Yakshagana (a dance-drama) and other art forms being performed in the dialect.

Gangolli says Kundapra Kannada was only a regional variant of Halegannada, or Old Kannada, that has miraculously remained largely untouched by further variations in mainstream Kannada.