- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

When many universities and research centres in the world gear up to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the discovery of ‘Lucy’, the 3.2-million-year-old partial skeleton of the oldest human ancestor that walked erect, a visit to the National Museum of Ethiopia to know ‘how we became humans’ makes sense. The museum houses three of the world’s oldest hominid fossils – namely Lucy,...

When many universities and research centres in the world gear up to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the discovery of ‘Lucy’, the 3.2-million-year-old partial skeleton of the oldest human ancestor that walked erect, a visit to the National Museum of Ethiopia to know ‘how we became humans’ makes sense. The museum houses three of the world’s oldest hominid fossils – namely Lucy, Ardi and Selam.

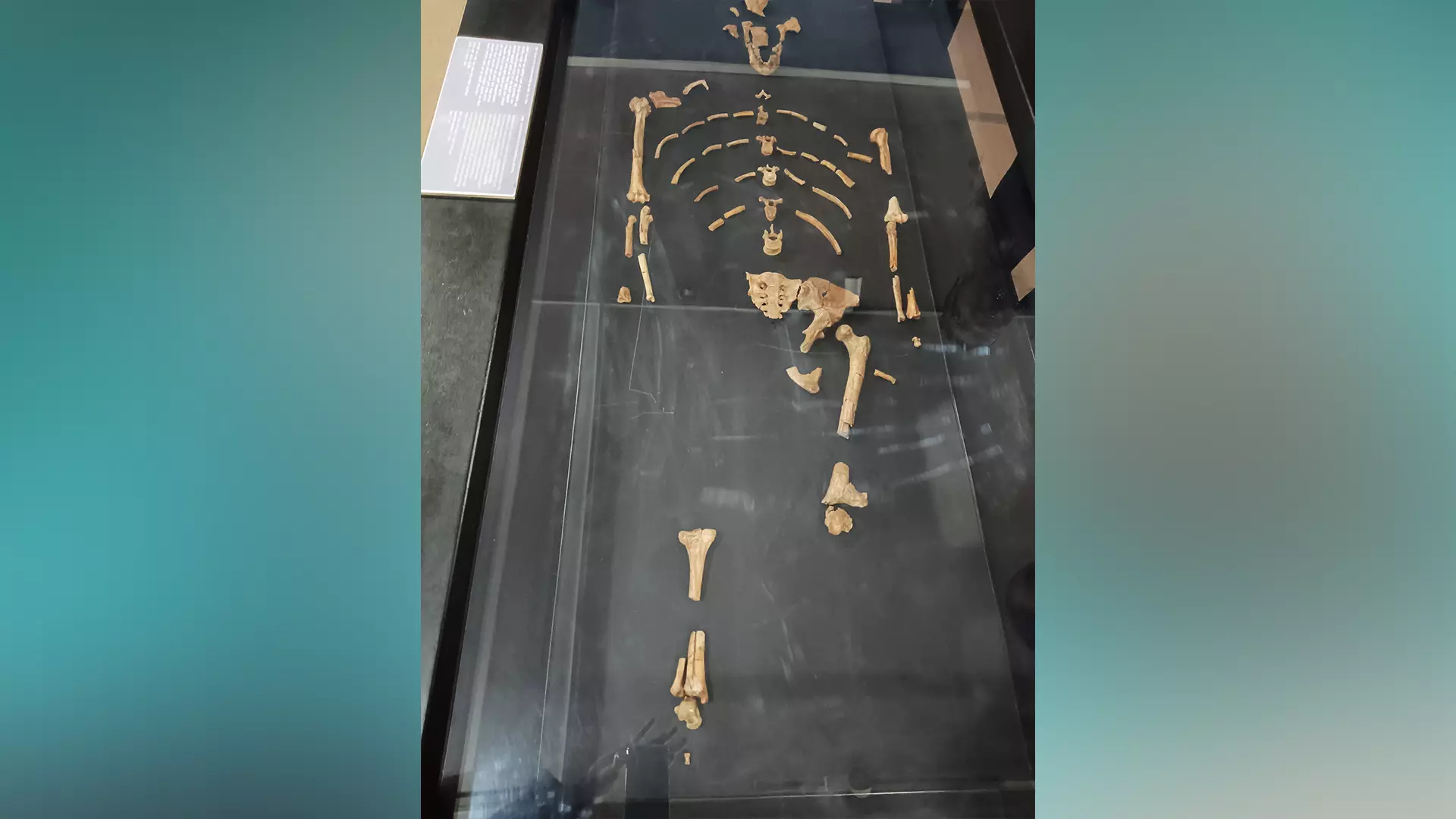

As you walk into the premises of the museum in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, you see that the building wears a deserted look, surrounded by cement sculptures of people in the garden. But the scene changes the moment you enter the ground floor of the building where you see ‘Lucy’, the 3.2-million-year-old partial skeleton of Australopithecus Afarensis, an early species of Australopithecus from which the later species evolved. When you stand close to these pieces of skeletons displayed inside a glass cage, you tend to lose your skills in mathematics. You don’t feel the length of 3.2 million years. You also forget the time zone that you are in. A close look at the skeletons and you forget the rest in the huge hall of the museum where only you and Lucy exist.

Many visit the museum to experience the ‘Lucy and I’ moment but only a few are able to establish ‘contact’ with Lucy. Why? If you are going to see Lucy, you should know her story in advance. Otherwise, you won’t be able to establish the connection.

It was in 1974 that American paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson found this oldest skeleton of hominin at a fossil site in Hadar in the eastern part of Ethiopia.

It was in 1974 that American paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson found this oldest skeleton of hominin at a fossil site in Hadar in the eastern part of Ethiopia. There are many interesting stories associated with Lucy, which got the name from the popular Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”. According to Johanson, his team of excavators was on cloud nine after the discovery of the oldest human ancestor and they played the Beatles song repeatedly on a tape recorder.

“The camp was rocking with excitement. The first night we never went to bed at all. We talked and talked. We drank beer after beer. There was a tape recorder in the camp, and a tape of the Beatles song “Lucy in the sky with Diamonds” went belting out into the night sky, and was played at full volume over and over again out of sheer exuberance. At some point during that unforgettable evening – I no longer remember exactly when – the new fossil picked up the name of Lucy, and has been so known ever since, although its proper name – its acquisition number in the Hadar Collection – is AL 288-1,” writes Donald Johanson in “Lucy, The Beginnings of Humankind: How Our Oldest Human Ancestor Was Discovered and Who She Was,” an account of the discovery of Lucy that he co-authored with Maitland Edey.

The National Museum of Ethiopia maintains three of the world’s oldest hominid fossils– Lucy, Ardi and Selam. Ardi, the 4.4-million-year-old partial skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus (an early human-like female anthropoid) was excavated in 1994 and 1995. Like Lucy, scientists believe that Ardi is female because of her tiny small canine skull. She stood about 120 cm tall and weighed about 45-50 kg, about the same size as female chimpanzees. Ardi combined tree climbing and bipedal walking on the ground. Her arms and hands were longer than in humans, but shorter than in chimpanzees. She was less acrobatic, more careful tree climber than chimpanzees. She walked with an outward pointing flat toot, and could not run or walk long distances as well as the later human ancestors. Selam, the 3.3-million-year-old partial skeleton of a three-year-old child, was unearthed at Dikika, south of Hadar, in 2000. It is currently under detailed study, but is already world famous as the best-preserved child skeleton of an early human ancestor. The entire skull, much of the neck region and upper body and parts of the lower body are preserved.

The National Museum of Ethiopia maintains a fabulous collection of stone tools from prehistoric era.

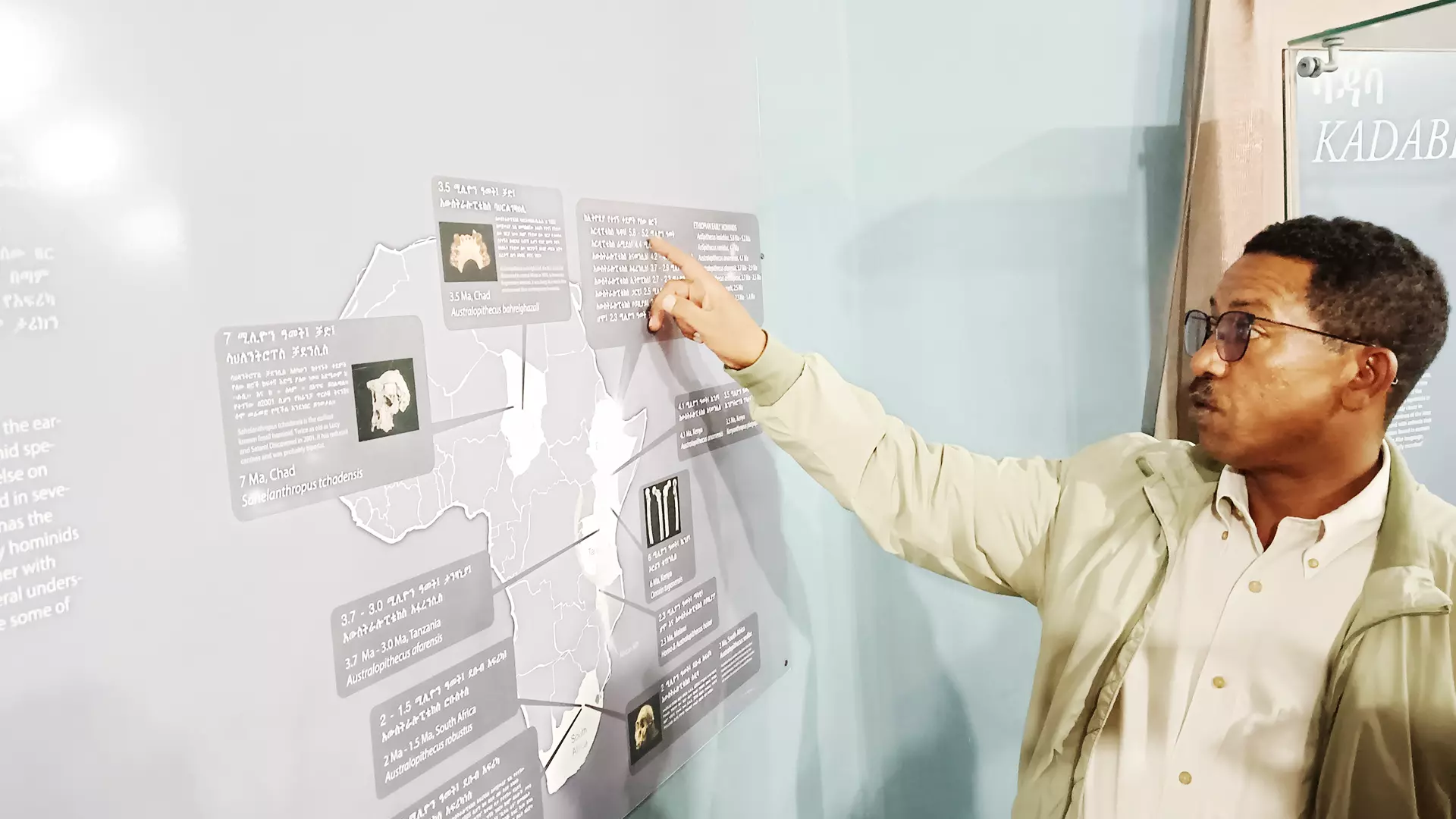

“Many ancient remains from various time periods were unearthed in Africa, from reptilian ancestors of mammals to the earliest known symbolic figurations realised by our species. Ethiopia is a unique place, with the most complete and richest record of human ancestors, and with the longest record of stone tool making. Most of the Ethiopian sites are found in the Rift Valley, which has been working as a giant fossil trap for the last ten million years,” says Abebaw Ayalew, director general of the Ethiopian National Museum and Ethiopian Heritage Authority (EHA).

Even though many in the city are not aware of the importance of Lucy, Ardi and Selam, the foreign scholars and researchers were keen on a detailed scientific research on the fossilised skeletons. In 2007, Lucy was taken to the United States for a six-year exhibition tour called “Lucy’s Legacy: The Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia”. Organised by the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences with the consent of the Ethiopian and US governments, the tour helped scholars to know more about the skeletons, particularly about Lucy, the centre of attraction. However, some renowned palaeontologists and anthropologists raised objections to the tour, citing the fragile nature of the skeletons. The exhibition tour, according to them, would damage many pieces of skeletons. Some institutes decided not to host the exhibition. The tour, however, lasted for almost six years, and Lucy finally returned to Ethiopia, her home, in 2013.

While the actuarial bones of Lucy are stored in a safe place at the Paleoanthropology Laboratories of the National Museum of Ethiopia, a plaster replica is displayed for the public with other skeletons and stone tools at the ground floor of the museum. “I visit the museum at least once every year. Africa is the cradle of humanity, and Ethiopia contributes a major share to it. Even though the Ethiopian government has set up a fantastic museum with great facilities, many people don’t know how to use it. Lack of awareness is the main reason. We need to create awareness among people about our great culture and civilisation,” said K Yoseif, a research scholar based in Addis Ababa.

Lucy, also called Dinknesh in Ethiopia (you are wonderful), was short and petite. This and the shape of her pelvis indicate she was a female. She was a young adult when she died. Studies have been ongoing since the discovery of Lucy in 1974. Even though the ancient human ancestor walked upright, it spent most of its time in the trees. With a height of 3.3-foot, she was shorter than us. Scientists also proved that she had a brain about one-third the size of a human brain. “Some 3.18 million years ago, Lucy’s body was slowly sinking in the mud of a lake. Fossilization was beginning. This process preserved her bones from destruction until scientists discovered them in 1974. Many other ancient remains — fossils and stone tools — persisted in Ethiopian rocks through ages. These remains tell us a long story of great transformation in landscapes, living beings and techniques. They tell us the long story of our ancestors,” says Abebaw Ayalew.

Abebaw Ayalew director general of the Ethiopian National Museum.

To understand how an extinct species may have moved, palaeoanthropologist Ashleigh LA Wiseman and her team recently reconstructed the missing soft tissues of the skeleton. The Australopithecus afarensis specimen AL 288-1 (Lucy) is one of the most complete hominin (any member of the zoological ‘tribe’ Hominini, of which only one species exists today—Homo Sapiens) skeletons. Despite having more than 40 years of research, the frequency and efficiency of bipedal movement of Lucy is still debated. The team reconstructed 36 muscles of the pelvis and lower limb of Lucy, using three-dimensional polygonal modelling, guided by imaging scan data and muscle scarring.

“On the basis of the muscle leverage results, Au. afarensis was capable of producing an erect posture but was also capable of using the limb in a repertoire of motions beyond habitual terrestrial bipedalism, in a similar manner to chimpanzees and bonobos, according to Wiseman. “As it stands, these results cannot confirm if AL 288-1 was an efficient biped, but rather that upright walking was a possibility. Moving forward, the polygonal muscle modelling approach has demonstrated promise for reconstructing the soft tissues of hominins and providing information on muscle configuration and shape filling,” writes Ashleigh L A Wiseman, in her findings titled “Three-dimensional volumetric muscle reconstruction of the Australopithecus afarensis pelvis and limb, with estimations of limb leverage,” published in the journal Royal Society Open Science in 2023. The scholar suggests further studies, to get a clear picture.

After Lucy’s time, our ancestors started to produce stone tools, according to Abebaw Ayalew. “This was a major shift in the history of human beings. It dramatically improved the way of life of our ancestry and made further cultural development possible. From this point, we not only deal with animal and plant remains or geological data, but also with human-made objects that are studied by archaeologists," he added. The museum maintains a huge collection of stone tools, prehistoric as well as modern.

“All human beings are hominids, but not all hominids are human beings,” says Donald Johanson in his book. As the discovery of Lucy completes its 50th anniversary this year, many universities have decided to celebrate it with lectures and talks. The Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins will celebrate the 50th anniversary of the “Lucy” discovery–A celebration of how we “became human” as a year-long programme with lectures and symposiums, exploring what the first bipedal ancestry continues to teach us about our ancient common past, our challenging present, and our boundless future. “We are happy that our country contributed immensely to the study of ancient humans and the way they lived through fossilised skeletons. The fossils help us know more about the history, the way of living and habitats of extinct species. We will continue the search,” said Ayalew.