- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

A journey spanning 400 million years with ammonites in Perambalur

When they first saw the spiral-shaped fossilised shells of the ammonites, they thought they were snakes turned into stones. While some treated them as sacred symbols, others used them as ‘snake-stones’ to protect them from insect bites and also to cure impotence and blindness. Who are these ammonites? If you ask this question to one who lives in Tamil Nadu’s Perambalur or Ariyalur, you...

When they first saw the spiral-shaped fossilised shells of the ammonites, they thought they were snakes turned into stones. While some treated them as sacred symbols, others used them as ‘snake-stones’ to protect them from insect bites and also to cure impotence and blindness. Who are these ammonites? If you ask this question to one who lives in Tamil Nadu’s Perambalur or Ariyalur, you can expect an answer immediately, as the region has been a treasure house of fossilised shells of ammonites and other sea animals. However, if you want to know more about ammonites, you need to take a walk around the Perambalur Ammonites Centre (PEACE), which houses more than 350 specimens of ammonites, including their life-size replicas.

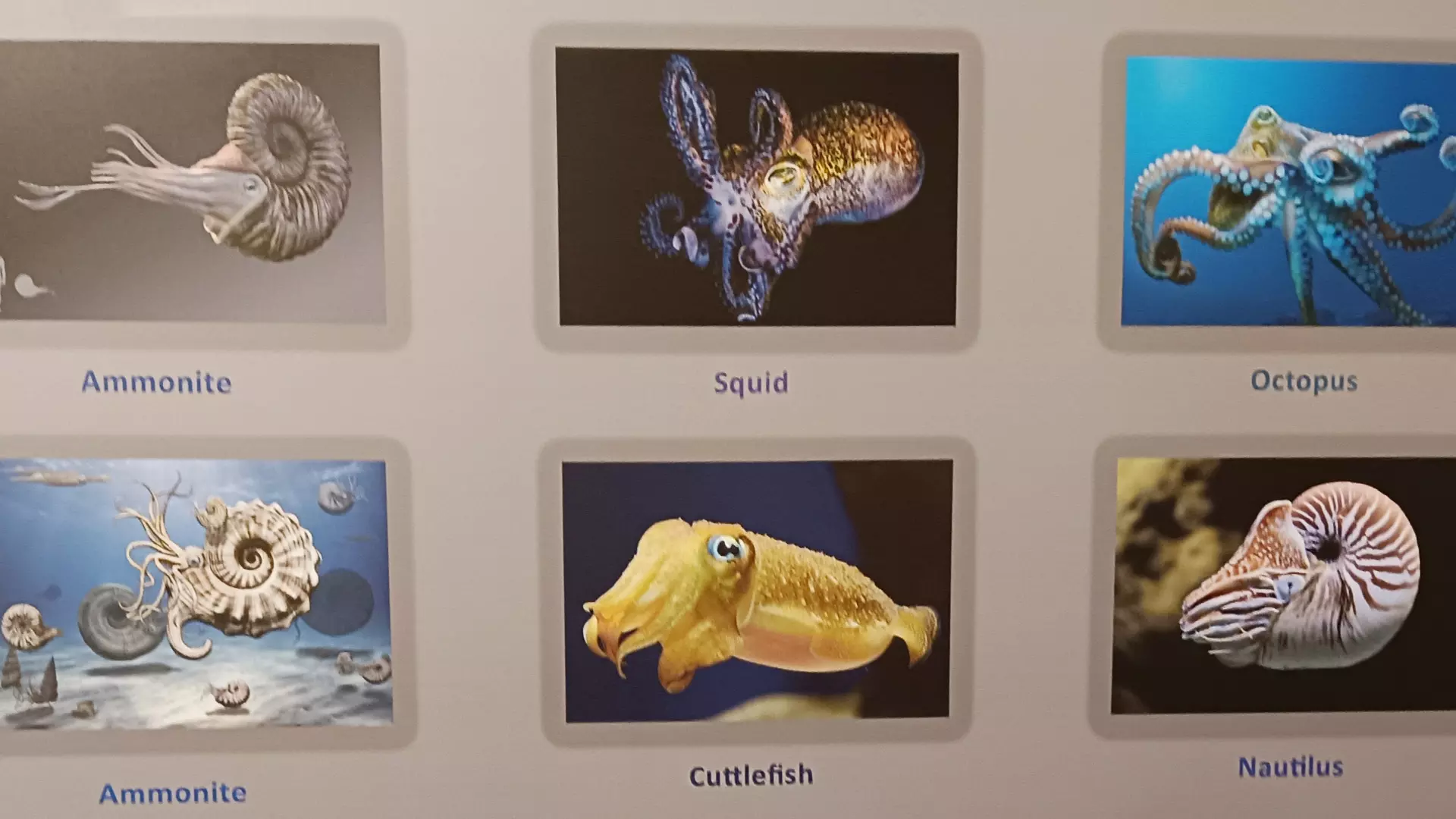

The story is more than 400 million years old. Ammonites lived on the shallow waters of our ancient oceans, feeding on phytoplanktons and other small crustaceans that floated on the surface. They started evolving during the periods of the Devonian (416 million years ago) and lived till the end of the Cretaceous (65.5 million years ago) era. Ammonites are related to other cephalopods such as squid, octopuses and cuttlefish and they were early relatives of the modern nautilus.

Ammonite fossils from Madagascar.

About 120 million years ago, today’s India was part of a vast landmass that comprised Australia, Madagascar and Antarctica. Convection currents drive the earth’s tectonic plates to move towards each other or split up and rift away. The Indian plate eventually split up and started drifting northwards away from Australia, Antarctica and Madagascar. This drift resulted in a rift that developed in three stages, across peninsular India and Sri Lanka. The rift stretches from today’s Trichy to Puducherry. Geologists believe that the Indo-Pacific Sea had transgressed between today's Puducherry and Karaikal regions and, after some 80 million years had regressed leaving millions of creatures dead in the dry sea bed. Today, one can see the traces of successive marine transgressions and regressions in the Cretaceous deposits of Perambalur, Ariyalur and Trichy districts. Perambalur’s Karaipadi, Odiyam, Karambiam, Kunnam, Karai and Kulakkanatham have fossilised remains of marine animals from the Cretaceous.

An ammonite fossil found on a rock in a village called Karambiam, in Perambalur.

As you enter the museum, you see a hoarding with a photograph of British biologist and natural historian David Attenborough with a quote, which reads:

“Extinction comes in different forms and many of the amazing creatures and plants alive today are also threatened. It’s possible that humanity is having as big an impact on the world as the asteroid that ended the age of the dinosaurs. As human beings, we are unique in our ability to learn from the distant past. Now, we must use that ability wisely and do our very best to protect the millions of species for whom, alongside us, this planet is home (Dinosaurs – The Final Day with David Attenborough).”

In this historic documentary, Attenborough brings to life the lost world of the very last days of the dinosaurs. Dinosaurs are popular mainly due to some animation films, but it was not the case of ammonites. About 10,000 species of ammonite fossils have been found around the world. At least 150 species of ammonites have been found and studied in Perambalur and Ariyalur.

The anatomy of ammonites is intriguing as most species had coiled shells lined with larger chambers separated by thin walls called ‘septa’, according to a hoarding put up inside the museum. The animals constantly grew new chambers as they aged, but their soft body parts with ‘tentacles’ always remained attached to their head in the outermost chamber. “The body was connected to the shell by intricate lines known as ‘sutures’. A thin, tubelike structure called a ‘siphuncle’ pumped air through the interior chambers of the shell that helped provide vertical movement and the muscular ejection of water through the ‘funnel’ gave them horizontal propulsion. Fossil evidence indicates that they had sharp, beak-like jaws to trap their prey,” says a brochure displayed at the entrance to the museum.

The Perambalur Ammonites Centre (PEACE).

Ammonites, however, exhibited sexual dimorphism. That is the male and female of a species were very distinct. Usually, the female ammonites grew larger in size than the male. There is evidence to suggest that in some species, the male had long projections from the forward edge of the body chamber. This could have helped to protect the animal, but they may have signalled maturity and fitness of breeding.

Ammonites are the most widely known fossil as they first appeared in the seas 415 million years ago, in the form of a straight shelled creature known as Bacrites, say Rajan S, M Jagadheesan and S Sathishkumar in their research paper titled ‘Studies on Fossils of Ariyalur, Tamil Nadu’. During their evolution three catastrophic events occurred. The first during the Permian period (250 million years ago), only 10% survived. They went on to flourish throughout the Triassic period, but at the end of this period (206 million years ago) all but one species died. Then they began to thrive from the Jurassic period until the end of the Cretaceous period when all species of ammonites became extinct.

“Ammonite fossils are found in every continent of the world. Because of their rapid evolution and wide spread distribution they are an excellent tool for indexing and dating rocks,” write Rajan S, M Jagadheesan and S Sathishkumar PG in the paper published in ResearchGate.

A reconstructed hanging sculpture of an ammonite found in the Karai Badlands.

Even though the fossils of ammonites housed in the museum don’t reflect any particular colour, scientists believe that their shells were decorated with an array of patterns and colours, indicating that exposure to light played a large part in their lives. “Ammonites moved through the water by jet propulsion expelling water through a funnel-like opening to propel themselves in the opposite direction. They mostly fed on molluscs, planktons, fishes and other cephalopods. Analogical studies show that they silently stalked their prey and grasped them quickly by using their tentacles. When caught the prey would be devoured by using its jaws, located at the base of the tentacles between the eyes,” reads an information board displayed at PEACE. The ammonites, however, also have served as food for other marine animals. There is evidence of mosasaurs and ichthyosaurs having eaten them. The lifespan of ammonites, according to scientists, is two years, but some lived beyond this period.

A marine family.

Even though there are more than 300 specimens of ammonites displayed at PEACE, a reconstructed hanging sculpture of an ammonite found in the Karai Badlands inside the main hall remains the centre of attraction here. It is based on a fragment of fossil found in the Karai Badlands.

“A broken fragment of a rare ammonite genus ‘Montoniceras’ was found in the Karai Badlands and was selected for the purpose of recreation. We tried our level best to recreate the ammonite in its live form. Inputs from many research papers of eminent palaeontologists and expert suggestions have gone into the making of this sculpture, especially for its texture, patterns, soft body parts, eyes, tentacles etc,” says Selvi, a guide at PEACE.

The largest ammonite fossil ever found was 5.9-foot across in Westphalia, Germany in 1895. Its living chamber, however, was incomplete. If the living chamber was complete, it would have been between 8.4-foot and 11-foot across. The fossil is housed at the Museum of Natural History and Planetarium, Munster in Germany. Why did ammonites go extinct? Scientists believe that a catastrophic collision of an asteroid with our planet by the end of the Cretaceous period caused the extinction of the ammonites. As they lived on the surface of the ocean feeding on phytoplanktons, ammonites became the first victims of the impact of collision than their closest relative nautiluses who lived deep in the sea.

Although Trichy, Perambalur and Ariyalur are rich when it comes to the fossils of marine animals, the region is yet to get the importance it deserves. For example, the Karai Badlands. Located along the Karai-Kulakkanatham stretch of Perambalur, Karai Badlands (a dry terrain where softer sedimentary rocks and clay-rich soils have been eroded) are an important region with natural conical mounds separated by gulleys and fossils of Cretaceous, a geological period which lasted from 145 to 66 million years ago. The topography of the Karai Badlands, according to geologists, is considered one of the rarest ones on earth which is similar to the Arizona province in the US. The Geological Survey of India declared it as a National Geological Heritage site in 2015 and following it, the Government of Tamil Nadu declared the badlands of Karai Formation with Cretaceous fossils as a geological heritage site for conservation, protection and maintenance.

“This place (Karai Badlands) shows the reference of 120 million years to 60 million years of sea submerged. Till now the topography of sea submerged places is present over here. The flora and fauna of the extinct paleontological species are frozen as fossils over here. We recommend the Union of India and state of Tamil Nadu to take necessary action to treat this place as a geologically important place globally,” says Ramesh Karuppaiya, a Perambalur-based environmentalist. “The state government has allotted funds to fence the badland topography. But that’s not enough. There should be a proper information centre with trained people to explain the topography and Cretaceous fossils. If the government gives training to local people, it will also help them find a source of income,” he adds.