- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

100 years on, how the great deluge washed away lives, colonial legacy and a grand rail line in Munnar

The year 1924, corresponding to year 1099 of ‘Kollavarsham’ the Malayalam calendar, marks a pivotal moment in Kerala's history. What began as the much-anticipated monsoon season, loved by the people, swiftly escalated into a catastrophic event that would later be remembered as the great deluge of 99. This devastating transformation not only reshaped the landscape but also left an...

The year 1924, corresponding to year 1099 of ‘Kollavarsham’ the Malayalam calendar, marks a pivotal moment in Kerala's history. What began as the much-anticipated monsoon season, loved by the people, swiftly escalated into a catastrophic event that would later be remembered as the great deluge of 99. This devastating transformation not only reshaped the landscape but also left an indelible mark on the collective memory of the state, forever altering its relationship with monsoon rains.

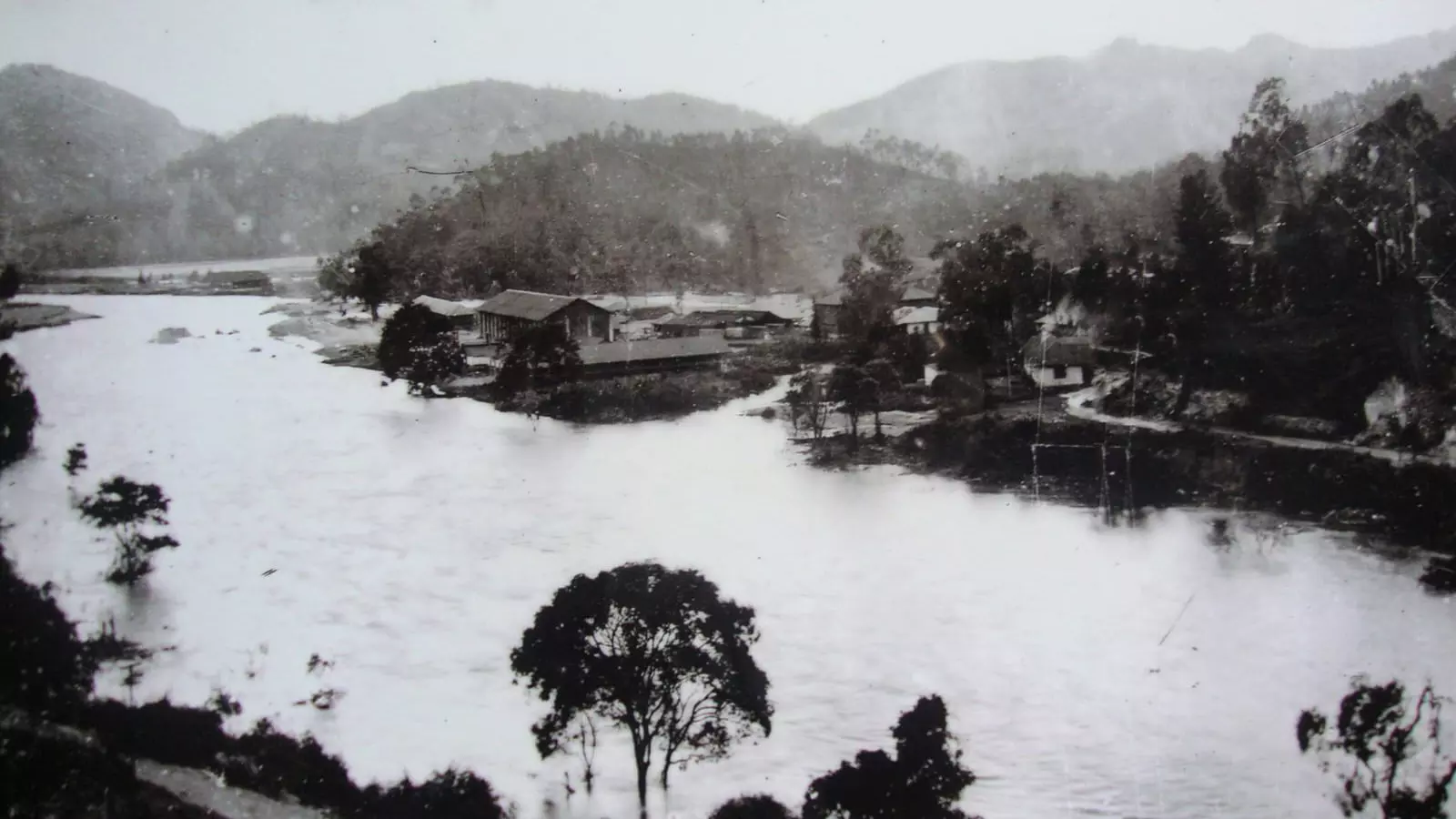

In August 2018, when Kerala experienced catastrophic floods once again that brought back memories of the deluge of 99. The flooding impacted the same regions, with rivers following their historical paths, causing widespread devastation. The similarities were striking, as the waters surged through the same areas, mirroring the events of 1924. The 2018 floods served as a stark reminder of Kerala's history with monsoon-related calamities, compelling the state to reflect on its past and future in managing such crises.

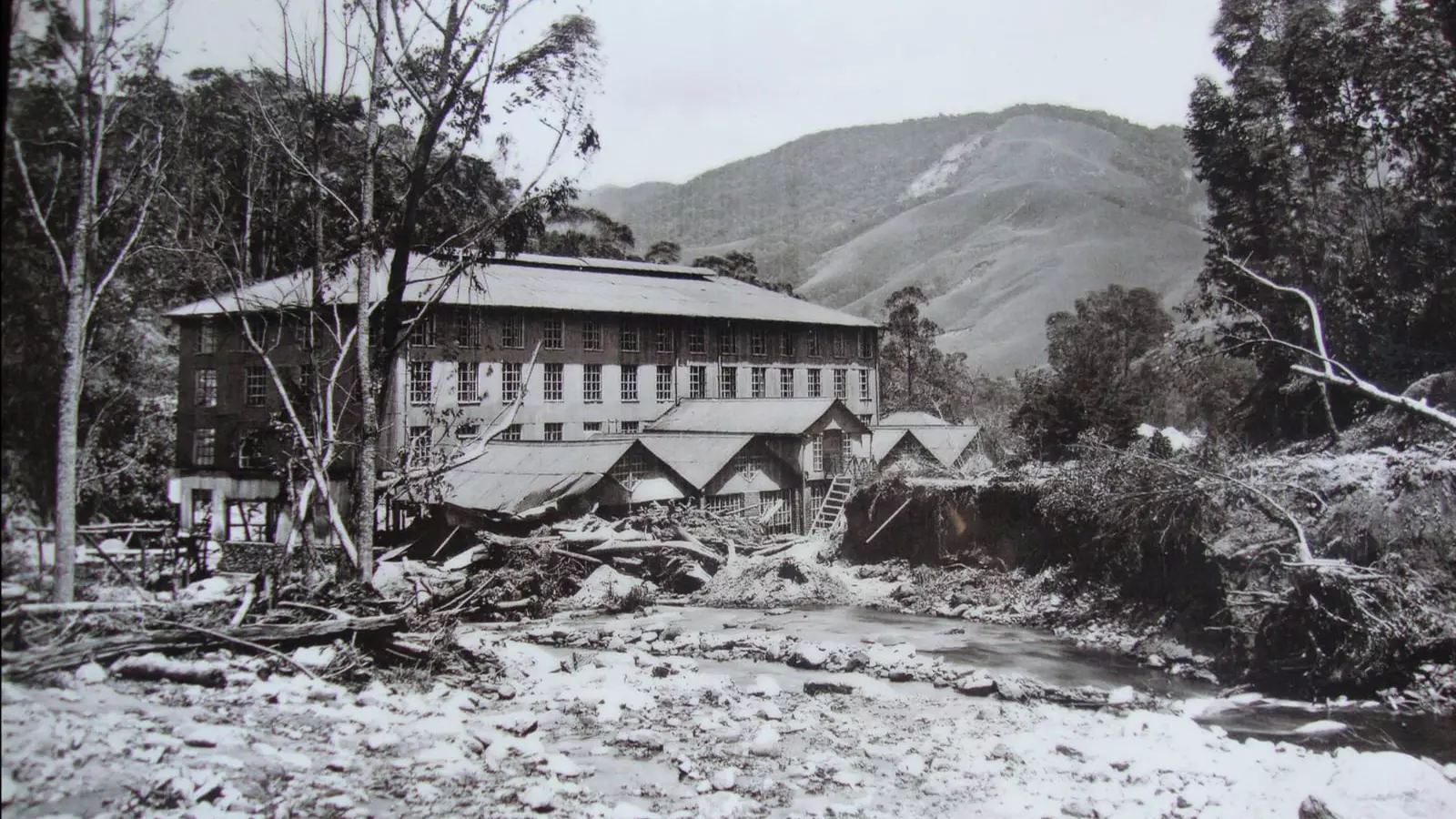

Among the casualties of the great deluge of 99 was India’s first monorail project, the Kundla Valley Railway of Munnar. Photo: Special arrangement

Now, with another monsoon pouring in, we go through the centennial of the great deluge of 99, the catastrophic event that claimed many lives and left a lasting impact on Kerala’s landscape. Among its casualties was India’s first monorail project, the Kundla Valley Railway of Munnar. This pioneering railway system, an engineering marvel of its time, was washed away in the floods, marking a significant loss in the annals of Indian transportation history.

According to several historical documents, in 1877, the King of Poonjar leased 277 acres of Kannan Devan hills to John Daniel Munro's British company for coffee plantation. The agreement between JD Munro and the King of Poonjar was ratified by the King of Travancore in 1879, enabling the establishment of the North Travancore Planting and Agricultural Society. In 1895, this society was transferred to a subsidiary of the Finley and Moor Company. A few years later, the Kannan Devan Hill Producing Company was formed. In 1964, Tata and the Finley groups collaborated to take over the company, with Tata eventually gaining sole ownership in 1973.

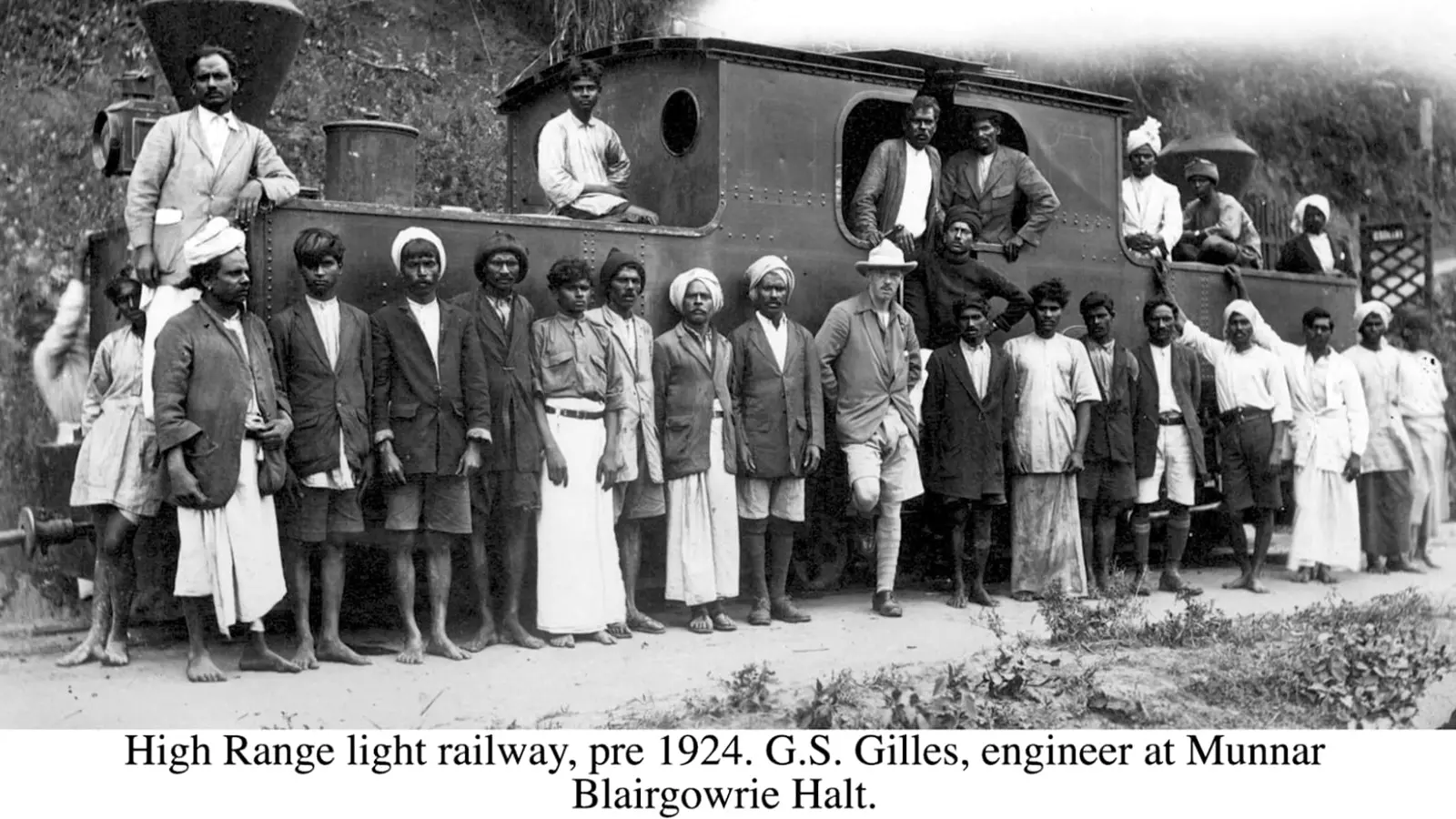

In the serene hills of Munnar, Kerala, where tea plantations stretch as far as the eye can see, lies a forgotten chapter of colonial history, buried under the passage of time and the wrath of nature. The Kundla Valley Railway or the old Munnar Railway, a British-era monorail system, later turned into a light rail or tram way, once served as the backbone for transporting spices and tea from Munnar to the bustling ports of Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu. This railway was crucial for shipping these valuable commodities — particularly tea boxes from the plantations — to England and various parts of India.

Constructed in 1902, the Munnar railway station, now the head office of Kanan Devan Hills Plantations (KDHP) Ltd, stood as a testament to British engineering and ambition. By 1908, the initial monorail, based on the innovative Ewing System (A balancing monorail system developed in the late 19th century by British inventor WJ Ewing), was replaced by a more efficient light railway. The equipment, including a steam engine imported from the UK, was meticulously assembled in Munnar, marking a new era of transportation and trade.

However, this chapter of progress and prosperity was abruptly closed in 1924 when the devastating deluge, unprecedented in its scale and ferocity, struck the region, washing away the entire railway system. The floodwaters tore through the landscape, dismantling the intricate network of tracks and bridges, leaving behind a trail of destruction that rendered the railway line beyond repair. This catastrophic event not only disrupted the vital transportation of goods but also erased a significant piece of Munnar’s colonial legacy.

The days of the floods are documented in various personal narratives, including memoirs and diaries of the Munnar residents at the time, mostly British. Mrs. Violette AFF Martin, the wife of AFF Martin, the then manager of the KDH tea plantations, wrote a personal account of the flood days. This account has been included in the centennial souvenir published by the Munnar GVHSS alumni association.

She has recounted the days starting form 15 July 1924 as follows:

“At Chundavurrai, where the writer was, 4.40 inches of rain had fallen from 6AM to 12 noon. An unusually large amount for July’ The rain was worse during the afternoon and a visitor who arrived then, spoke of the water as being near the top of the bridges in some places.

“Early in the morning of 16 July, the rainfall at Chundavurrai A huge landslip had taken part of the cart road away and carried all the debris towards the back of a set of 20 room coolie lines. News came up from the factory that the bridge near the muster ground had gone. The lines were cut off, and the only bridge by which to reach the bungalow was barely two feet above the water (sic).”

Madam Violette then describes their ‘excitement’, noting that one of her guests, a manager and his daughter, went out for an 'adventurous inspection’.

“The earth and water were pressing heavily against the middle of the houses and the occupants were at once turned out. To save the rest of the rooms, two brave carpenters went up to saw through the rafters and so separate off the threatened part of the building. This was accomplished just in time. The next right rooms were carried away into the river. A huge flow of mud and trees followed them.”

According to Mrs Violet, they had to cut short the adventurous inspection trip as it was a close shave. She puts in record that five of the seven bridges on the main road collapsed on that single day.

“At that time, the Kannan Devan Hill plantations tea factory (Now owned by Tata) and market were located where the Mattuppetty dam now stands, and the railway passed through that area. The combination of hill runoff and landslides created an artificial lake where the dam reservoir is now, causing significant flooding. It is believed that the railway was destroyed on the night of July 17. By July 18, the old town of Munnar was completely submerged, including the Munnar Supply Association building, Anglo-Tamil Primary School, and Heather Lodge. Workers had to climb onto the roof of the association building to escape. The water did not flow downstream but formed another reservoir where the Attukad waterfall is now, leading to more and more severe landslides,” says MJ Babu, senior journalist and local historian.

The floodwaters tore through the landscape, dismantling the intricate network of tracks and bridges, leaving behind a trail of destruction that rendered the railway line beyond repair.

Today, as one walks through the tea estates of Tata, scattered remnants of the 35-kilometre railway line can still be found, silent witnesses to the transformative power of nature. These relics of the Old Munnar Railway stand as a poignant reminder of the 1924 flood, a natural disaster that reshaped the region's history and landscape, forever altering the course of Munnar's colonial narrative.

RS Mani, the former vice-president of Devikulam Block Panchayat, is the oldest living Malayali born in Munnar. He has clear memories of the hill station and its British era, but his recollections of the flood and the rail line come from stories he heard from his grandfather.

“I am the third generation living in Munnar. My grandfather came here to work on a dam. Now, at 80 years of age, I've heard stories about a flood that destroyed the rail line. The British had brought all the machinery from England and assembled it in Munnar. During the flood, everything was swept into the river. Scrap dealers cut up the metal and sold it, with some people using the rail iron to build gates. There were three railway stations: Top Station, Central Station, and Bottom Station. Tea was transported to Thoothukkudy port by lorries run by the state government transport corporation,” recollects Mani from the stories he had heard from his grandfather.

“The railway line ran from Munnar to Top Station, with tea boxes transported to Ammainaickanur railway station (now Kodai Road Station) in Tamil Nadu, and then shipped to Thoothukkudy Port. Foreign travellers also used this route, traveling from Sri Lanka to Tamil Nadu and then taking a ropeway from Kurangani to Munnar,” says MJ Babu.

“Initially, the railway was a Patiala model monorail with two large wheels on the sides and a smaller wheel in the middle. Bullocks and ponies were used, and oxen were imported from Europe. By 1908, the light rail was in place. Instead of restoring the railway, the British company installed a ropeway to transport tea boxes,” Babu added.

“I still recall the constant hum of the ropeway cars operating from morning to evening, with tea boxes suspended on the ropes even through the night, unattended. There were no thefts, as there was no market for the product, and the company managed it all very efficiently,” says RS Mani.

It was during the rule of CP Ramaswami Iyar, the diwan of Travancore, the transport of Travancore's produce through other states was restricted, so goods were diverted to Kochi port. The government later bought lorries for transporting tea and issued an order that no other vehicles should be on the road while the lorries were in operation.

In the aftermath of the deluge, efforts shifted from rail to road. A new route was established, towards the east, connecting Munnar with Top Station and further to Kodaikanal in Tamil Nadu. However, the dense forest terrain eventually led to the cessation of vehicular traffic on this route, further isolating the remnants of the old railway. Towards the west, the Aluva-Munnar highway took an entirely new alignment thanks to the local influential politicians in the lower part of Idukki districts.

“The Aluva-Munnar road was completely destroyed and was not restored; instead, a new highway was constructed via Neriamangalam. Due to the low population in the area and lack of demand for the old road, there was no push for its restoration,” observes MJ Babu.

In 2019, the state government launched a project to restore the hill railway as a tourism initiative, with some announcements made in the state assembly. The Tata company reportedly agreed to transfer the land required to reconstruct the Kundal Valley railway line, aiming to operate a tourist train similar to those in Ooty or Shimla.

“The tourism department is yet to follow up on the rail restoration project. Railway officials made a few visits, but no further actions were taken,” says MJ Babu.

With the centennial of the great floods of 1924, the Old Munnar Kundal Valley railway line has once again become a topic of discussion. A three-day exhibition at Mount Carmel Church parish hall in Munnar, on July 17-19, which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the 1924 Great Flood, provided a clear picture of how the hill station had evolved over the last century. The exhibition showcased a rare collection of photos taken during the flood and news clippings from that time. This event added to the growing demand for the tourism project related to the Old Munnar Kundal Valley railway line.