- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

x

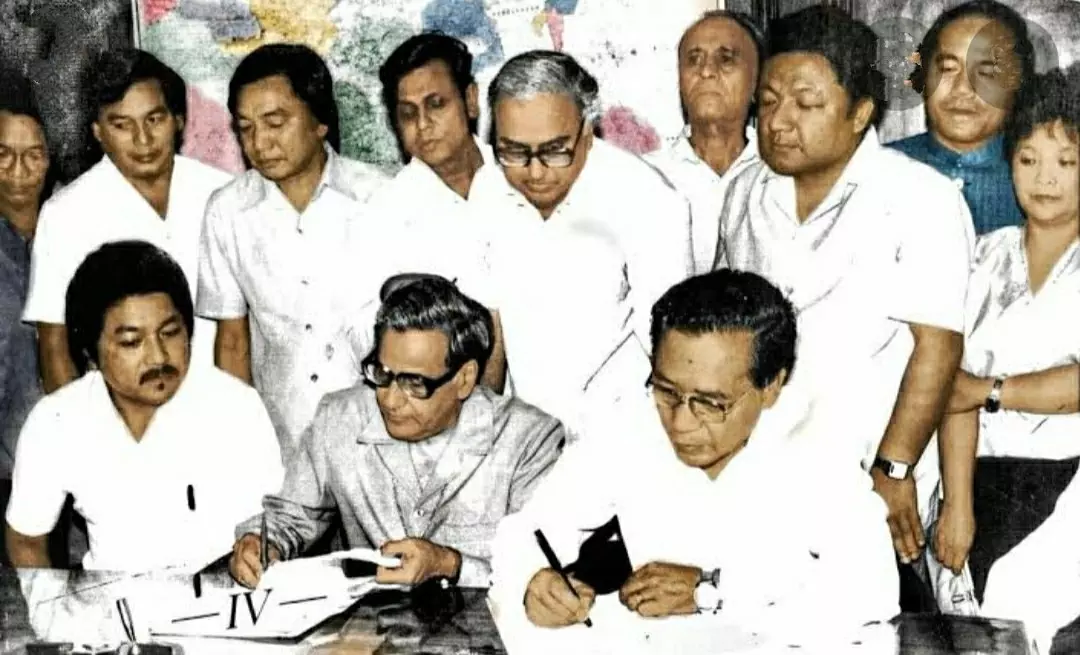

The Mizo Accord exemplifies the spirit of accommodation that marks post-colonial India's tryst with destiny as a plural entity. Photo: Facebook

38-year-old pact is a good model of conflict resolution, exemplifying spirit of accommodation that marks post-Colonial India's tryst with destiny as a plural entity

Post-Colonial India has few achievements to celebrate. Some of them come with a date that can be observed across the country but are not.

December 16, 1971 and June 30, 1986 are two such dates Indians can celebrate.

Birth of Bangladesh

The first marks the decisive victory of the Indian armed forces and the Bengali guerrillas over Pakistan’s brutal army, the day the Pakistani army commander Lt Gen Abdullah Niazi signed the instrument of surrender in the Suhrawardy Udyan of Dhaka to India’s eastern army commander Lt Gen J S Arora.

The surrender paved the way for the vivisection of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

More than a military victory, this is the day that established beyond doubt the inadequacy of Jinnah’s "Two Nation" theory as the organising principle of post-colonial South Asia.

Lessons from a neighbour

Bangladesh’s creation answers so many questions that India now faces.

To those who seek azadi in Kashmir, Bangladesh may be an inspiration of sorts. But those like Syed Ali Shah Geelani who advocate merger with Pakistan would do well to ponder – Bengali Muslims who formed the majority in undivided Pakistan could not get justice; what could Kashmiri Muslims expect by joining Pakistan?

But Pakistan’s determination to incorporate Kashmir, as opposed to India’s desire to see Bangladesh emerge a free nation, itself negates the prospect of any change in the status quo, regardless of all the intense violence one has witnessed.

Mizo Accord

The second such day is June 30, 1986 – the day the Indian government, led by then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, signed the Mizo Accord with the Mizo National Front (MNF), paving the way for peace to return to a hill region scarred by two decades of bloody insurgency.

The accord in Mizoram has endured well and is now seen as a model of conflict resolution and peace making. Above all, it exemplifies the spirit of accommodation that marks post-colonial India's tryst with destiny as a plural entity.

The Union is held together by consensus and not by the guns of the Indian Army, which has played a brilliant role in taking the sting out of many a insurgency but stepped aside at the right time for the political process to take over.

Mizoram celebrates this day as 'Remna Ni', or Peace Day, but the rest of India seems to not even be aware.

Where India won

If accommodation and reconciliation is the strength, not the weakness, of the Indian federal system, Mizoram was our finest hour.

Where Pakistan failed so miserably in 1971, India did not, and June 30, 1986 exemplifies the very spirit that holds India together.

Visit capital Aizawl and you will come across Thlanmual or Matyrs Monument that the state government, led by the MNF (which ruled Mizoram for two full five-year terms) built in 2008 to remember those of its guerrilla fighters who fell fighting for Mizo independence.

That such a monument can co-exist alongside our own military memorials saluting Indian troops for defending the integrity of India exemplifies the very spirit that holds India together – this is a joint family where acrimony and misunderstanding is handled by dialogue, not just by the stick and Mizoram resembles the spirit in substance and form.

Spirit of reconciliation

The sons and daughters of those who fought India so vigorously in the ‘Rambuai’ (troubled) years now man the levers of Indian administration in ever-increasing numbers and footballers like JJ (Jeje Lalpekhlua Fanai) and Shylo Malswama do India proud by outrunning defences and scoring goals against formidable rivals.

To underscore this very spirit, India could do well to celebrate June 30 as Reconciliation Day, much as we could celebrate December 16 as Victory Day to drive home the graveyard of the "Two Nation" theory unless someone is seeking to resurrect Jinnah in India.

One would help us put Mizoram and the North-East on the country’s thought map, the other would help us bond ever more closely with our friendly eastern neighbour.

Naga problem

The Narendra Modi government should also take a leaf out of the Mizo peace process to absorb the right lessons that would help it resolve the Naga problem, the longest festering ethnic insurgency India has ever seen.

After signing the framework agreement in 2015 that was to pave the way for a final Mizoram-type accord, the Naga peace process has hit a huge roadblock over widely-divergent perceptions of shared sovereignty.

Some would say it has lost its way. That should not be the case. In a federal system as young as India, reconciliation should be accorded highest priority.

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)

Subir Bhaumik, a veteran BBC journalist and author, worked for Myanmar's leading media group Mizzima as Senior Editor.

Next Story