- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

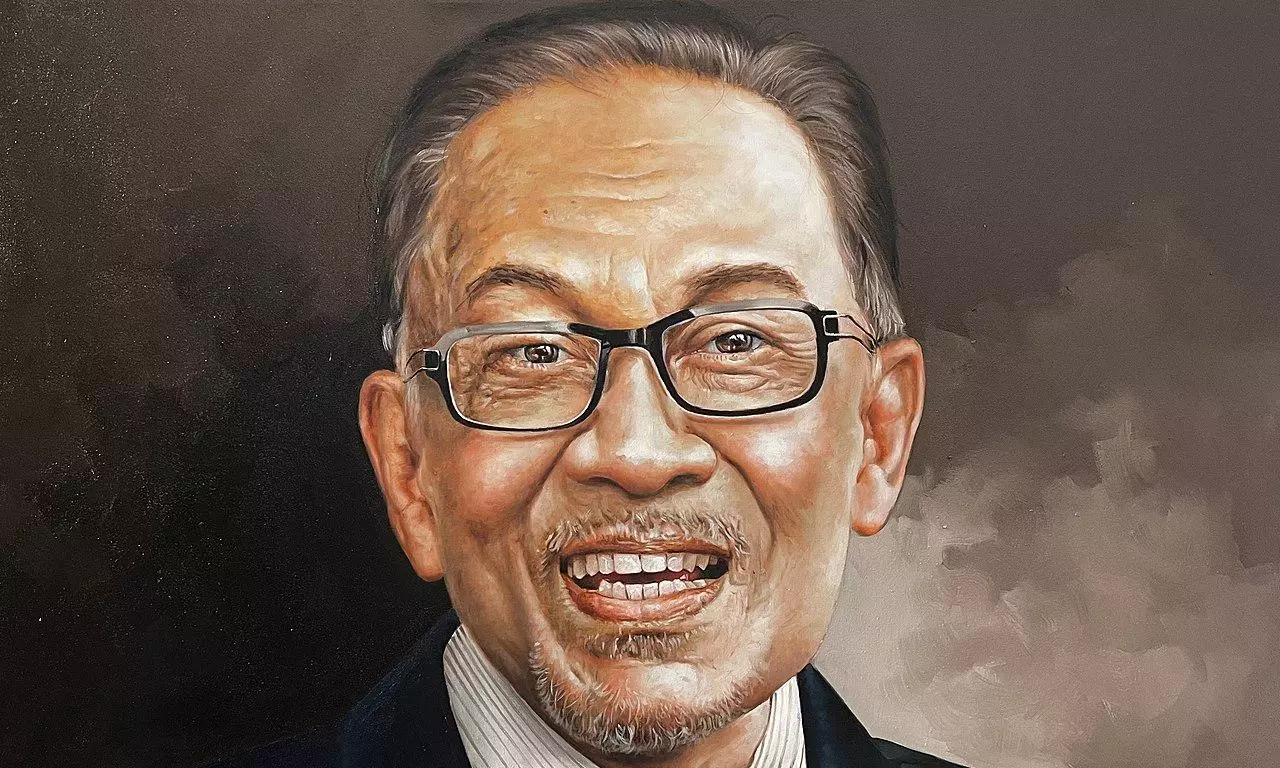

Between a ferocious opposition, a thin majority in parliament, and growing discontent within Malay majority constituency, Anwar has become a circus acrobat

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has expanded his cabinet by appointing five new faces in his latest move to consolidate power in a disparate ruling coalition. But hopes of reforms he promised after his 2022 electoral triumph have faded fast, raising question marks over political stability in this multilingual Southeast Asian nation.

The five new faces Anwar inducted in his cabinet include Gobind Singh Deo, the first-ever Sikh cabinet minister, in charge of the communications and multimedia portfolio, and another Indian-origin lawmaker, M Kulasegaran from the Democratic Action Party, who has the human resource portfolio.

Anwar brought about these changes when accused of power monopoly for adding the finance portfolio to his prime ministership.

The new second finance minister, Amir Hamzah Azizan, has been the CEO of Malaysia’s Employees Provident Fund, after 25 years in national energy company Tenaga Nasional, Petronas and Shell.

Economic reforms

The government has launched ambitious economic plans, including the Madani economy framework, National Energy Transition Roadmap, New Industrial Master Plan and the mid-term review of the 12th Malaysia Plan. But political reforms, needed to minimise corruption and mindless horse-trading, have not materialised. Analysts say the much-needed structural reform has not happened because Anwar cannot risk being perceived as responsible for measures that could compromise the economic share of Malays ensured through affirmative reservations.

They say a better approach would be to demonstrate that these reforms will expand economic opportunities for all and provide a time-bound financial cushion to those hit hardest. The 2024 Budget Speech, where some of the government’s economic agenda will be announced, is an opportune time to do so, analysts say.

The government's reform agenda was further compromised after Anwar appointed UMNO’s scandal-ridden President Zahid Hamidi as deputy prime minister. The Public Prosecutor's decision to absolve him of all corruption charges surprised all and sundry.

In Malaysia, the Offices of the Public Prosecutor and Attorney General are held by the same person. So, the government needs to take the civil society's appeal for separating the two offices to avoid political interference in legal matters.

The minister of law and institutional reform has recently announced plans for reform, but needs to expedite them urgently or risk been seen as not serious about change.

Analysts say Malaysia must rekindle its reform agenda quickly but take care to let the majority Malays (Bhumiputra or Sons of the Soil) enjoy economic benefits. But this will prove challenging, especially with an increasingly strong opposition that has used racially divisive language to elevate Malay insecurity, says Tricia Yeoh, CEO of IDEAS, an independent public policy think tank in Malaysia.

Rather than falling deeper into UMNO’s political cracks, Anwar needs to revamp the Reformasi that Malaysians have been voting for.

Racial divisions

In November 2022, Anwar Ibrahim, 75, leader of the democratic movement Reformasi, finally became prime minister of Malaysia. He had spent eight years of a 20-year struggle in prison for “sexual offenses” that he claimed were politically motivated. His party, Parti Keadilan Rakyat, is the only multiracial formation in a highly racialised landscape where all parties are religion- and race-based.

Though Malaysian politics has followed racial divisions even before Independence (ethnic Malays in United Malay Nationalist Organisation or UMNO, the Chinese in Malayan Chinese Association or MCA and the Indians in Malayan Indian Congress or MIC), the race-based parties managed to share power and avert an Indian-style partition. That has largely changed now.

Considering the context of the global threats against democratic systems, and the country’s past hijacking of democratic institutions by autocratic political agendas, the Anwar government’s “Malaysia Madani” or “Civil Malaysia” seemed timely but it failed to appeal to Malays, who are exhausted by years of economic distress.

Building on its success in 2018, Pakatan Harapan (PH), Anwar’s coalition, campaigned on its reform agenda and renewed its intention to fight against corruption. However, in his rise to power, Anwar made a seemingly impossible compromise by allying with his former enemies in the scandal-ridden former ruling party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), which cast a shadow on the legitimacy of his reform agenda.

UMNO’s electoral loss in 2018 landed its president and former prime minister Najib Razak in prison in August 2022, where he now serves a 12-year jail sentence on charges of abuse of power and corruption.

Corruption charges

The 1MDB case and the lesser-known SCR case implicated not only top Malaysian leaders but also Hollywood stars and Wall Street financiers. The 1MDB case was a sophisticated and flagrant embezzlement operation centered around Malaysian financier Jho Low, who is likely currently in hiding in China. These cases generated much public distrust in state institutions and opened a rift between UMNO and its traditional supporters in the Malay majority.

Since then, the political landscape has shifted, allowing the emergence of new players like opposition party Bersatu and paving the way for new alliances. The Malay majority is now split between Bersatu, Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) and UMNO. Anwar’s PH party faces a crisis of legitimacy, since its supporters are not from the Malay majority, which is why PH must hold on to a relatively weaker UMNO.

In this complex landscape, and for its own survival, Anwar appointed his long-time friend and Najib’s party successor, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, as deputy prime minister in November last year. This decision elicited controversy as Zahid was then facing 47 separate charges of criminal breach of trust, corruption and money laundering related to the embezzlement of $27 million from a charity he funded to fight against poverty. Last week, Zahid was cleared of all charges.

Anwar’s alliance with UMNO in the PH coalition represents a Cornelian dilemma that is perceived by his supporters and the international community as the lesser of two evils: the return to power of UMNO in Anwar’s coalition blocked the ascension of another powerful Malay coalition – Perikatan Nasional (PN) – that includes Bersatu and PAS. But analysts believe that Anwar’s alliance with UMNO has atomised the Reformasi agenda and led to the country’s stagnation.

Precarious position

Faced with constant threats, Anwar is in a precarious position, and democratic reforms have taken a back seat. Between UMNO and a ferocious opposition, a thin majority in parliament and growing discontent and fear within the Malay majority constituency, some say Anwar has become a circus acrobat. His fruitless attempts to please the Malay crowds coupled with his efforts to maintain influence within his own circles have led the prime minister down a path of populism and confusion, sparking criticism from both external civil society organisations and within his own ranks.

Malaysia’s elections watchdog Bersih and the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs exposed the many political appointments made from within Anwar’s circle of supporters to manage government-owned companies or to occupy top positions in business conglomerates owned by his campaign funders. Human rights organisations warned against Anwar’s contradictory positions towards LGBTQ+ rights and exposed the Ministry of Home Affairs’ intentions to amend the constitution by removing provisions that protect children against statelessness.

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)