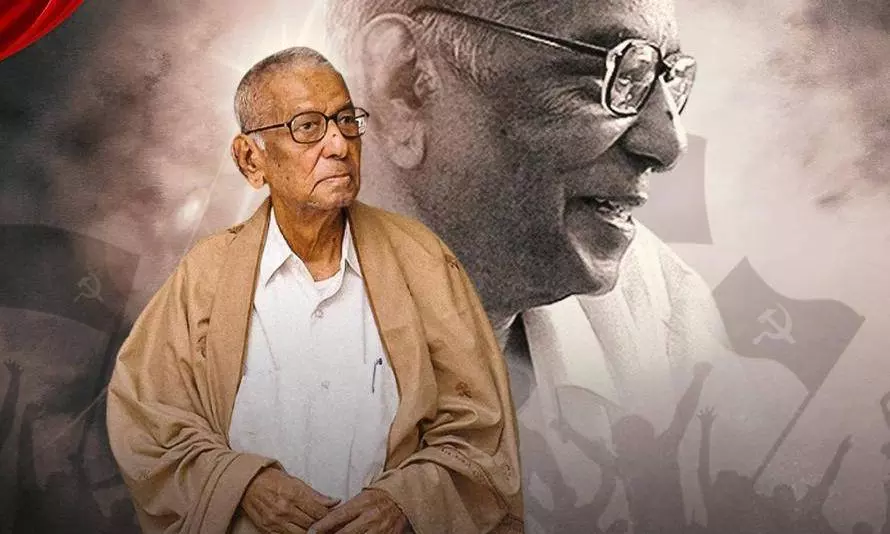

Obituary | When Sankaraiah said, ‘We fought for freedom, not pension’

He sacrificed his degree for the freedom struggle and was denied an honorary doctorate just before his death because the Governor refused to sign the order

On a pleasant December afternoon in 2019, I accompanied veteran journalist P Sainath to interview N Sankaraiah. The interview was published in People’s Archive of Rural India website and Sainath’s book – The Last Heroes: The Foot Soldiers of Indian Freedom.

Sankaraiah was living in a modest house in one of the narrow lanes of Chromepet in Chennai. The people in his neighbourhood were not aware of the tall leader living in their midst. Things would change in two years after the DMK took over. The government conferred the first Thagaisal Thamizhar award on Sankaraiah. Chief Minister MK Stalin would descend on this modest residence to confer the award on the leader.

When we met him, Sankaraiah was 99, and for that age, exuded a rare kind of energy. He vividly remembered his childhood, his introduction to Kudiyarasu, the Dravidar Kazhagam magazine, thanks to his maternal grandfather who was a Periyarist. He remembered how “Tamil Nadu was on the boil” after the execution of Bhagat Singh and his comrades. Sankaraiah was hardly 9 years old and had participated in a demonstration at Thoothukudi.

“It was a turning point in Tamil Nadu’s history of freedom struggle,” he said.

He took particular pride in the inter-caste and inter-communal marriages that had taken place in his family. Sankaraiah himself married Navamani, a Christian teacher from a Communist family in September 1947. The wedding took place at the party office in Madurai and was officiated by veteran communist leader P Ramamurthy.

His association with the Left movement started in 1940 when Sankaraiah was still in college. Sankaraiah’s first arrest happened when he was a college student – he was picked up in 1941 for condemning the arrests of his friends who protested against the British. He was arrested barely fifteen days before his final BA examinations. When he was finally released 18 months later, it was too late to write his exam. Sankaraiah was increasingly drawn towards the freedom struggle and the Left movement.

Sacrificed his degree for freedom struggle

In his book, Sainath notes how the American College could have taken a cue from the Tamil Nadu government and honoured one of its ‘most distinguished’ students. After all, ‘he was one of its top students and couldn’t get a degree only because he went to prison, for his country’. Even as the State government decided to confer an honorary doctorate on the veteran leader, Governor RN Ravi refused to sign the order and put it on hold. It didn’t matter that Sankaraiah was the second accused in the Madurai Conspiracy case officially recognised by the government of India as part of the freedom movement, or that he had come out of jail only a day before India got its independence.

Sainath also mentions how Sankaraiah had turned down the freedom fighter’s pension, and contributed the Rs 10 lakh that came along with the Thagaisal Thamizhar award to the Chief Minister’s Covid relief fund.

“We fought for freedom, not pensions,” he had said.

Maniyammal and other women Communist leaders

During the interview, we asked him about Keezh Venmani and his association with Maniyammal, the communist leader who helped build the party in and around Thanjavur.

In December 1968, the tiny village of Keezh Venmani in Nagapattinam district witnessed the gruesome murder of 44 Dalit agricultural labourers, including women and children, by a landlord Gopalakrishna Naidu. The murders followed the protests of the labourers, organised by CPI(M), seeking higher wages.

“When Keezh Venmani happened, I was at a conference in Kochi and visited the place after two days,” Sankaraiah reminisced. “Today, we have a memorial there and the Left movements remain strong. In Thanjavur, we combined economic struggles with social struggles, including untouchability”.

Manalur Maniyammal, a widow, was a sort of Communist legend who worked tirelessly among the farmers in Thanjavur and the surrounding areas in the 1940s. It is believed that she died after being hit by a deer in 1953. Sankaraiah recalled how she would attend the Left meetings in a dhoti and a shirt.

“She was hugely respected by the agricultural labourers of east Thanjavur. There were other women leaders too like KP Janaki Ammal, Papa Umanath, Parvathi Krishnan, and others. They were involved in farm movements, in trade union activities, and more,” Sankaraiah said, his voice beaming with pride.

When he was mentioning a farmers’ conference in 1945, we asked him if he had expected India to be independent in the next twenty months.

“We never expected it at all,” he said. “We only knew the struggle was going on and it would go on.”

A temporary phenomenon: Sankaraiah about BJP’s dominance

At 99, Sankaraiah still read the newspapers. Images of him reading Theekathir, CPI(M)’s official newspaper, when he turned 100 were published. He kept himself abreast of the political developments in the State but was never one to be worried about it.

As a veteran Communist leader, even the advent of the BJP as an unassailable force at that point in time didn’t worry him much.

“We have been part of the original freedom struggle,” he said. But went on to add: “It is a temporary phenomenon. But it is important not to let your guard down. You need to keep fighting.”

He told us how he had grown up as a “disciplined member of the Communist party and how he thinks the party will get the right response in electoral politics in due time.” That we were told to ask the party first before seeking his interview perhaps elucidated how Sankaraiah was committed to remain a disciplined member of the party, even if he was not as active.

It was perhaps one identity that N Sankaraiah fiercely held on to till his death – a disciplined member of the Communist party.