Interactive: Why the Western Ghats are crying for protection

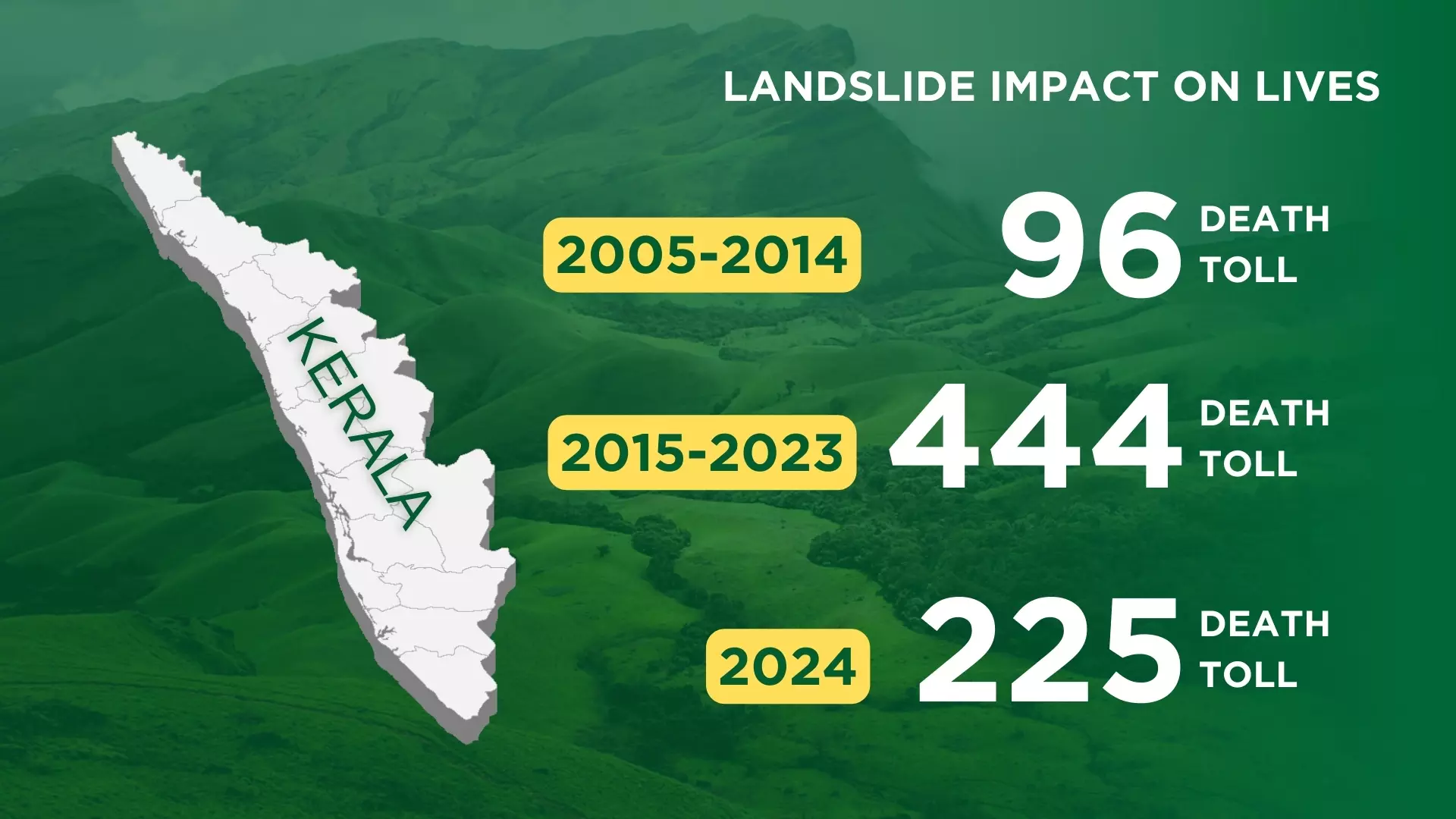

Recent landslides in Wayanad that killed over 200 people once and cause massive destruction again emphasised how important it is to conserve the region

The July 30 landslides in Wayanad that killed over 300 persons and caused extensive destruction have once again emphasised how important it is to conserve the Western Ghats.

Central to the conservation programme is the demarcation of Ecologically Sensitive Areas (ESA) in the six states that host the Ghats.

The Centre has, over the years, sent the states six drafts for the declaration of ESAs, first per the recommendations of the Gadgil committee report of 2011 and later per the Kasturirangan committee report of 2013. None of these has been implemented by the states.

The Western Ghats are a mountain chain even older than the Himalayas. They consist of exceptionally vast biological diversity and endemism and are recognised as one of the world’s eight ‘hottest hotspots’ of biological diversity.

Failure to demarcate ESAs and protect the region could lead to a series of disasters including landslides, floods and threats to rare flora and fauna.

The Federal presents the issue through five interactive graphics.

Where are the Western Ghats?

The Western Ghats run down the western side of India for about 1,600 km. There are peaks that vary in height up to around 2,700 m.

The Ghats stand as a barrier between the West Coast and the rest of the Indian peninsula, covered by the Deccan Plateau.

The Western Ghats begin from the Satpura Range south of River Tapti in the north, running about 1,600 km to the southern tip of India, and end at the Marunthuvazh Malai at Swamithoppe in Tamil Nadu's Kanyakumari district. The range covers an area of 1.6 lakh square-km.

The Western Ghats meet with the Eastern Ghats at Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu before continuing south.

The mountains are roughly divided into three parts: the northern section with an elevation ranging from 900–1,500 m, the middle section starting from the south of Goa with a lower elevation of less than 900 m, and the southern section where the altitude rises again.

The Western Ghats have several peaks that rise above 2,000 m, with Anamudi (2,695 m) being the highest. The average elevation is around 1,200 m. The Ghats host various national parks, as seen in the chart below:

How rich is the ecological chain?

The Western Ghats are home to rich biodiversity, including numerous endemic species:

Mammals: Endemic species like Lion-tailed Macaque, Nilgiri Tahr, Indian Elephant, Bengal Tiger, Indian Leopard

Birds: Over 500 species like Malabar Grey Hornbill, Nilgiri Wood-pigeon, White-bellied Treepie

Reptiles: Endemic species like King Cobra, Malabar Pit Viper, lizards and geckos

Amphibians: Diverse amphibians, particularly frogs like Purple Frog and species in Raorchestes genus

Flora: Tropical evergreen forests with vast array of plant species, including economically important ones like sandalwood and many medicinal plants

This biodiversity hotspot is crucial for conservation efforts, given the number of unique species that reside here.

What are the major violations?

The Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage site, face numerous environmental challenges due to human activities. The interactive chart below lists the main concerns in each of the six states hosting the Ghats.

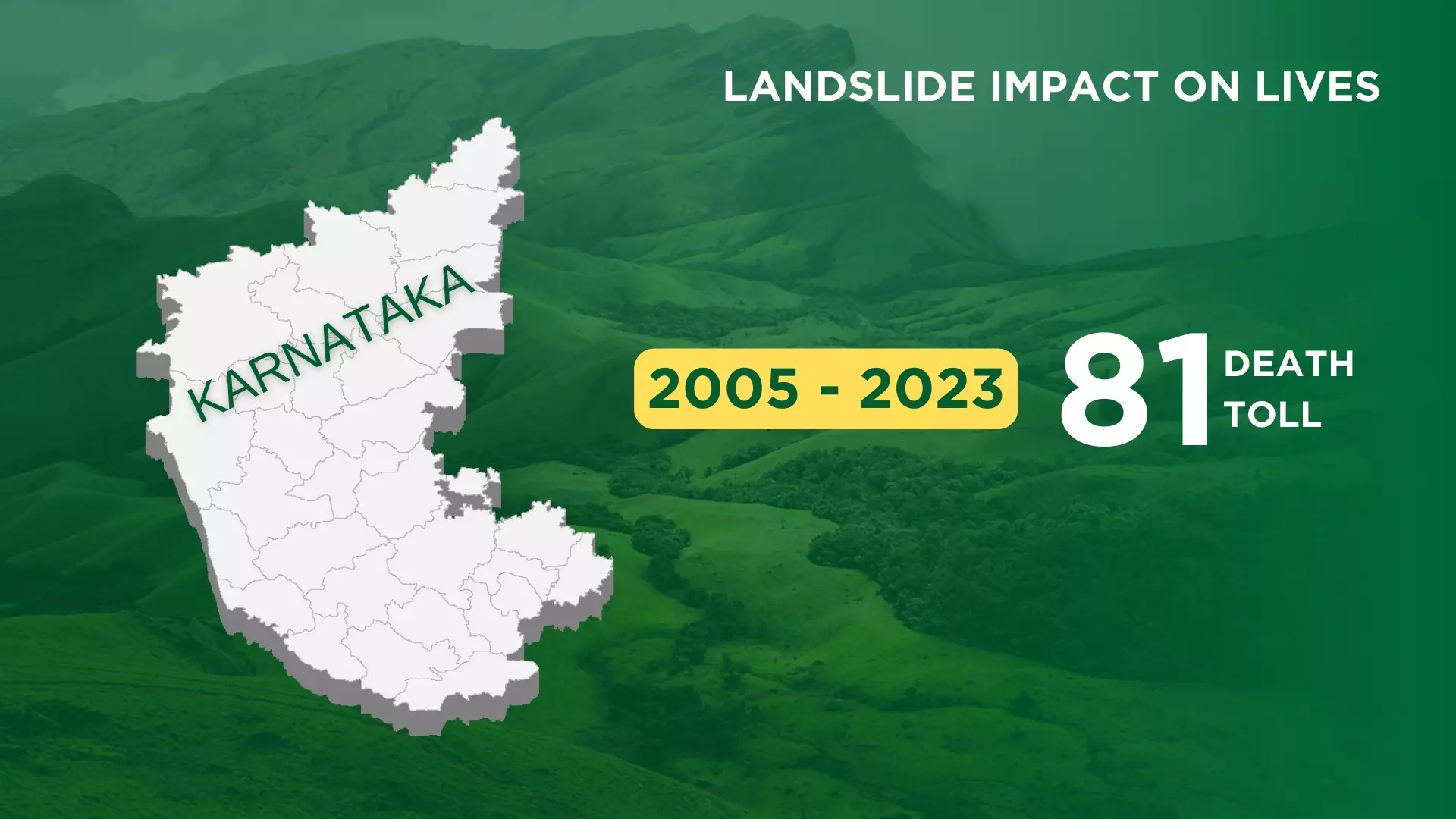

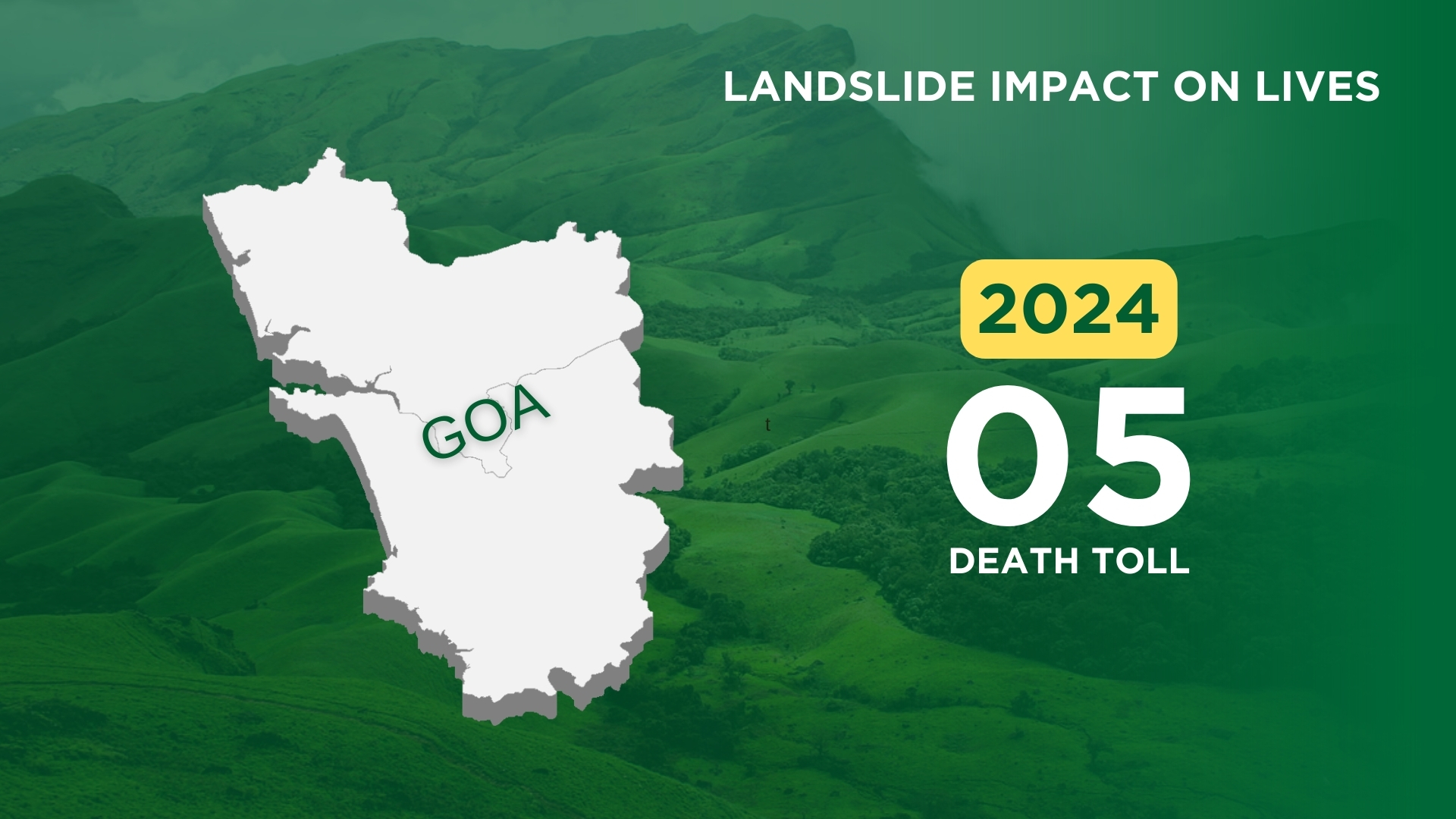

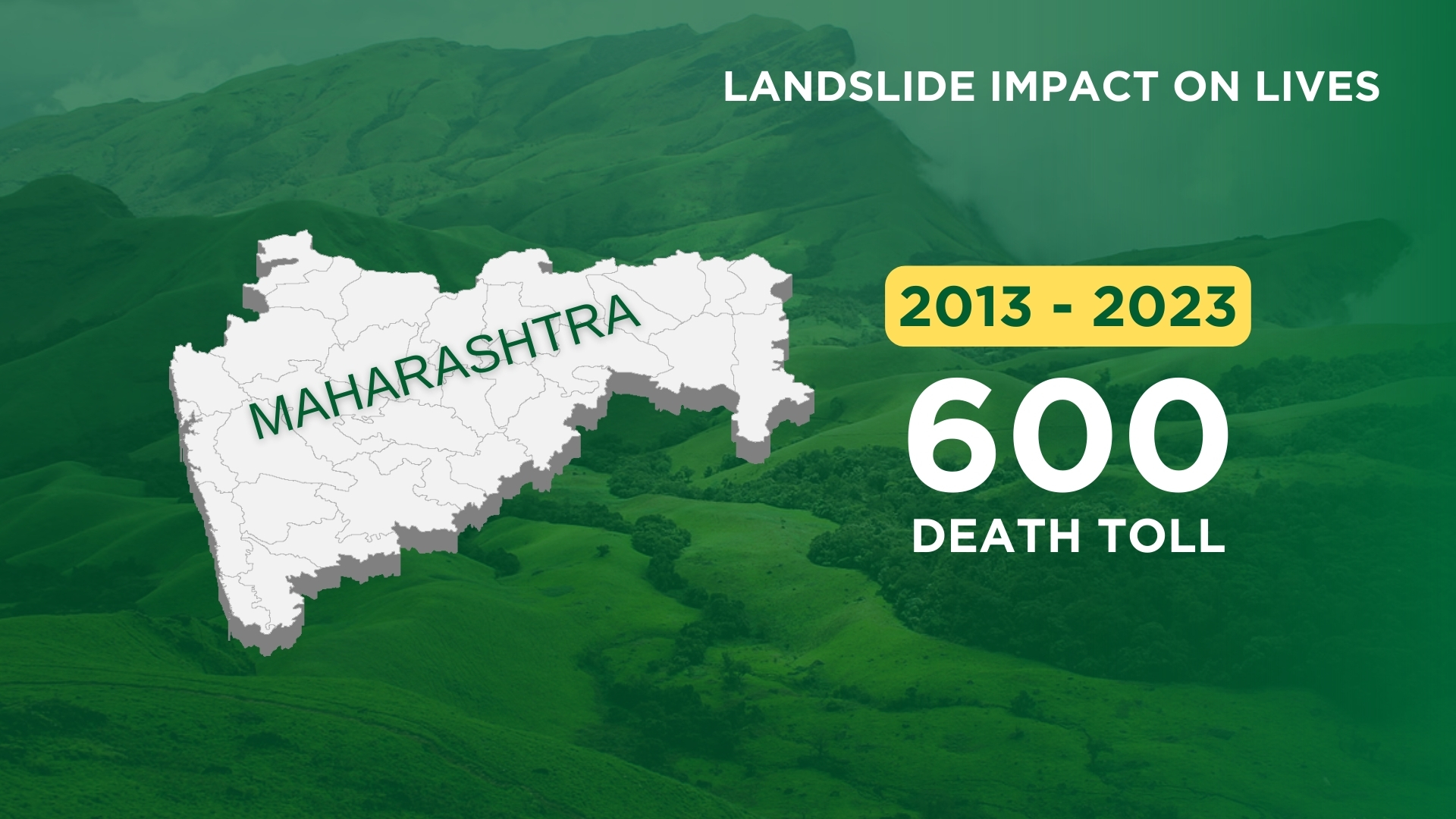

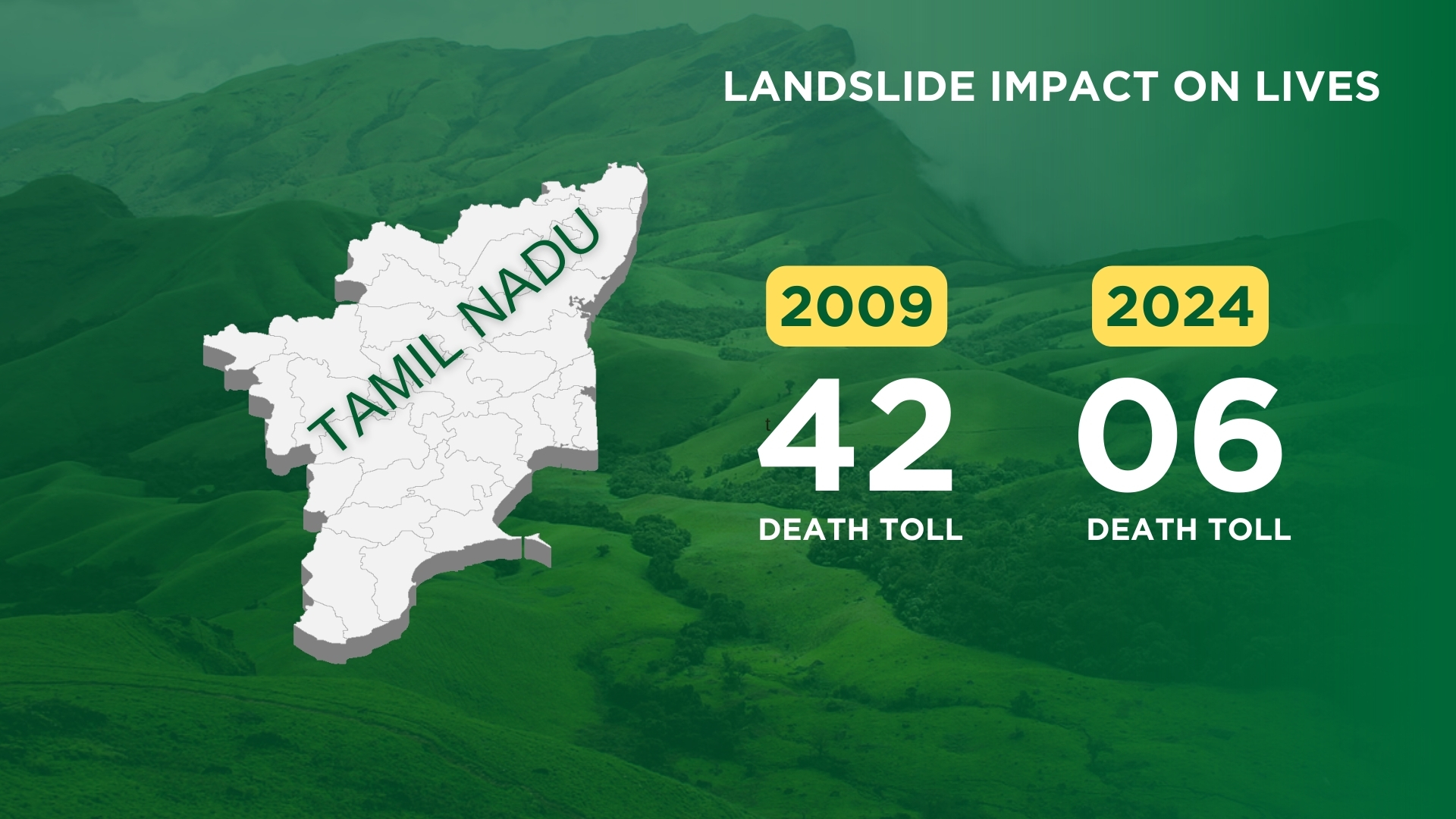

Big landslides in Western ghats since 2005