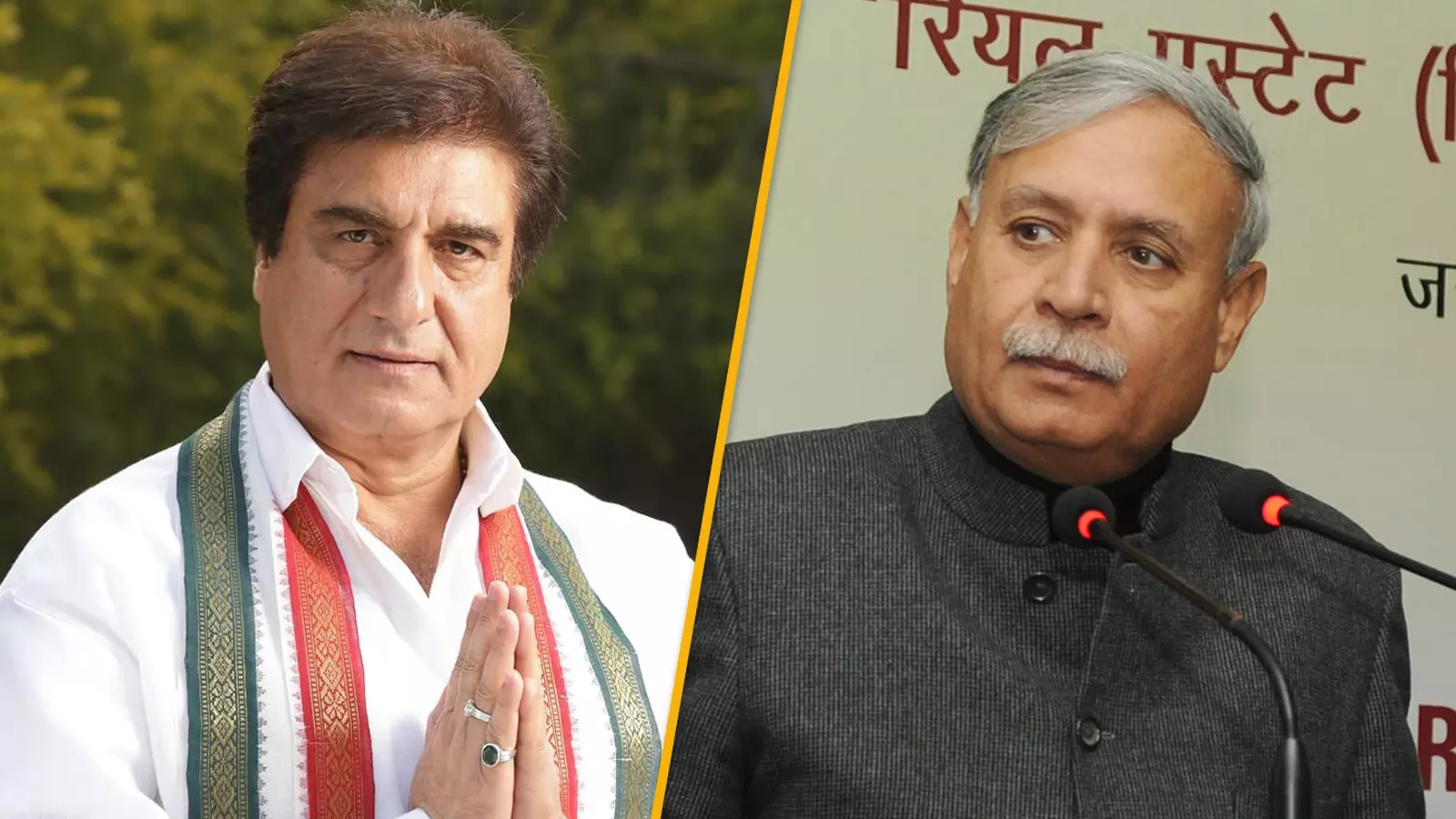

Congress' Raj Babbar fights an unequal poll battle against BJP's Rao Inderjit in Gurugram

Caste arithmetic, outsider tag weigh down actor-politician as he takes on 'absentee' Union minister in a deeply polarised constituency

When the Congress party declared actor-politician Raj Babbar as its candidate from Haryana’s Gurugram Lok Sabha constituency last week, the announcement shocked and surprised party members and rivals alike. Babbar’s candidature defied all considerations of caste arithmetic, availability of strong local alternatives, Congress’ own past precedent of candidate selection and, some argue, even winnability.

The 71-year-old was picked by the party, sources say after hectic lobbying on his behalf by former Haryana chief minister Bhupinder Singh Hooda, over former five-term legislator and Congress veteran Capt. Ajay Singh Yadav. A Punjabi Sonar (goldsmith) by caste, Babbar is the first non-Yadav candidate to be fielded by the Congress from Gurugram, a constituency with a predominantly Yadav and Muslim electorate.

'Outsider' tag

Though Babbar may be a rare Hindi cinema actor to have transitioned into a career politician in the late 1980s and survived for nearly four decades the wily intrigues of politics across three parties – the Janata Dal, the Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Congress – his electoral karmabhoomi had always been Uttar Pradesh.

Predictably, the BJP, which has once again bet on incumbent Gurugram MP and Union minister Rao Inderjit Singh to wrest the seat, has been prompt in dubbing Babbar as an “outsider” to the constituency. It’s a charge the 71-year-old actor-politician is repeatedly denying each day, recalling his “childhood spent in Gurugram”, while also asking why the same charge isn’t levelled against Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who “left his home state of Gujarat to contest Lok Sabha polls from Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh)”.

On his part, Babbar has been trying to steer the poll narrative in Gurugram to a somewhat omnibus plank on which he believes he can pin down the BJP and Rao Inderjit, a five term Lok Sabha MP and once the Congress’ Ahir (Yadav) face in Haryana.

Campaigning in the Jharsa locality of Gurugram, Babbar hard-sells himself as a leader who will “always be available to solve your problems like a family member” and slams his BJP rival for being an “absentee MP”. He rues the “crumbling civic infrastructure” of Gurugram, once pegged as ‘Millennium City’, and asserts that “despite contributing the largest share of revenue from the state to the central and Haryana treasury, the past 10 years of BJP rule has given Gurugram only bad roads, irregular water supply, poor law and order and power shortage”.

Poll rhetoric ticks the right boxes

While on the campaign trail in the Muslim-dominated and economically impoverished Nuh district, which falls within the Gurugram Lok Sabha constituency, Babbar adds to this list of BJP’s failures issues of “rising unemployment, inflation and politics of communal polarisation and hatred”.

The issues Babbar highlights and the accusations he hurls at the BJP tick all the right boxes. Anyone who has visited Gurugram would readily testify that despite its impressive and imposing townships and corporate parks, the city neighbouring the national capital is an urban nightmare replete with potholed arterial roads, non-existent public transport (barring the Metro Rail), frequent electricity outages, high prevalence of crime, et al. Travel further across the Lok Sabha constituency to unspectacular assembly segments of Bawal, Rewari (in the Rewari district), Nuh, Ferozepur Jhirka and Punahana (Nuh district) or parts of Gurugram district’s Badshahpur, Sohna and Pataudi segments, and the socio-economic inequity gets even more apparent.

What impair Babbar’s winning chances

Yet, despite a poll rhetoric that is easily believable, for its evidence stares one in the face all across the constituency, what is equally palpable is that Babbar needs nothing short of a miracle to wrest the seat from Rao Inderjit. For, while the Congress candidate may have issues on his side, what he lacks is the social arithmetic of castes and communities as well as the command over a party organisation at the grassroots – both factors that remain visibly in favour of his BJP rival.

Across the nine assembly segments that fall under the Gurugram parliamentary constituency, the electorate’s voting preference is sharply polarised between the Congress and the BJP. While the saffron party holds sway over the five assembly constituencies of Bawal, Badshahpur, Sohna, Gurugram and Pataudi, the Congress has traditionally been strong in Rewari, Nuh, Ferozepur Jhirka and Punahana. Former chief minister Om Prakash Chautala’s Indian National Lok Dal (INLD), which once had pockets of influence across the Nuh and Gurugram districts, is now a pale reflection of its past glory owing to the split in the party that gave birth to Dushyant Chautala’s JJP five years ago.

Polarised electorate

This sharp political divide aside, voting patterns in past elections also show clear consolidation of two unequal blocks of within the electorate, though this division isn’t entirely party oriented. Gurugram has two dominant communities, the Hindu Ahirs and the Meo Muslims which comprise an estimated 18 and 20 per cent of the electorate, respectively. Other caste and community groups with smaller concentrations include the Punjabis (about eight per cent), Dalits and tribals (about 13 percent, Jats (about seven per cent), Gujjars and Brahmins (both at about four percent).

Senior journalist Anil Tyagi says if voting trends of the past continue, Rao Inderjit will have “another easy victory”.

“Take any of the past elections as a yardstick and you will see that a staggering 80 per cent of the Ahirs in Gurugram always vote for an Ahir candidate and it is only when there is more than one strong candidate from the community that this vote sees some split. Rao Inderjit is the tallest Ahir leader in Gurugram; he comes from a royal background, is the son of a former chief minister (Rao Birender) and has been a Lok Sabha MP five times (twice from Mahendragarh and thrice from Gurugram). All of this puts him at a natural advantage against Babbar. Also, don’t forget that Inderjit left the Congress to join BJP only in 2014 and even as a BJP member, he has not played the communal card, which makes him an acceptable figure even in Muslim dominated parts of Nuh,” Tyagi says.

Why influence of Ahir community matters

“In 2019, the Congress had fielded Capt. Ajay Yadav against Inderjit but what happened. Inderjit won by a margin of 3.68 lakh votes because the Ahirs, along with other communities, voted overwhelmingly for him. This was because while BJP’s cadre-based vote is limited to the four assembly segments of Gurugram district, Inderjit also has his own loyal vote-bank across the Ahir-dominated Rewari because of his family legacy. Babbar, on the other hand, is an outsider and belongs to a caste that is not just relatively small in number but is already committed in its party affiliation to the BJP. It is a fight of unequals and even if Babbar, being a Congress candidate, gets a majority of the Muslim votes from Nuh, it is highly unlikely that he will substantially dent Inderjit’s prospects in Gurugram and Rewari,” Tyagi adds.

These distinct polarities that Tyagi mentions are visible on the campaign trail too. While Babbar’s public meetings and door-to-door campaign receives a visibly tepid response in the urban localities of Gurugram, he got a hero’s welcome while visiting Nuh.

Atul Mahajan (42), a resident of Sector 39 in Gurugram, where Babbar was campaigning on May 6, conceded that though poor civic infrastructure was a “major concern” that the BJP had failed to address, he would still “vote for the BJP” because he “admires Narendra Modi”. Babbar’s celebrity status, Mahajan said, was “not a draw” in Gurugram because “nowadays so many actors come into politics... he is not even a star and the young voters have no attraction for him”.

Sharing a similar view, Rajvir Dahiya, a real estate broker who attended one of Babbar’s corner meetings in Gurugram’s Jharsa, told The Federal, “people may go to see him because this is election time and he is also from the film industry but they will eventually vote for the BJP candidate... this is a BJP stronghold”.

Riot-rattled Nuh bats for Congress

The reactions to Babbar across Nuh district, however, were almost euphoric, though not because of his celebrity status. With scars of the communal violence that claimed seven lives in Nuh last August still fresh in public memory, a common refrain across the district is that the Congress must win to restore social harmony.

“Even if Babbar had not come here to campaign, he would have still got our vote because only the Congress has been talking about communal harmony. Across Haryana, Mewat has faced the worst brunt of BJP’s communal politics and we will respond to it with our vote. Rahul Gandhi had also come to Nuh during his Bharat Jodo Yatra and we had welcomed him with open arms; it had become clear back then itself that every single vote from Nuh will go to whoever the Congress fields in the Lok Sabha election. The riots of last year have only made that resolve deeper. Everyone here wants Modi out of power because of his communal and anti-Muslim politics,” said Rafey Alam, a shopkeeper in Ferozepur Jhirka.

In Punahana and Nuh, bulldozers were used to shower flower petals on Babbar while Congress members and ordinary citizens alike gave him loud assurances of their support in the election. That his candidature was backed by Bhupinder Hooda became an added bonus. “If Hooda and the Congress have trusted him with winning this seat, we will give him our full support. For us to live in peace, it is important for the Congress to win,” Punahana resident Aftab Hussain told The Federal.

The divisions of castes, communities and their party affiliations are expected to grow even starker as Gurugram draws closer to polling day – May 25 – and the campaigns by Babbar and Inderjit gain momentum with Modi’s communal diatribe and the Congress’s counter-charge on livelihood issues looming large in the backdrop.