Fmr CEA deflates Modi govt assertion on economic growth rate

India overestimated its overall growth by 2.5 percentage points between 2011-12 and 2016-17 and the actual growth was only around 4.5 per cent, says ex Chief Economic Advisor, Arvind Subramaniam.

Subramaniam who was CEA for a four-year period during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first term has made this startling revelation in a paper at Harvard University.

The revelations are bound to raise the hackles of UPA regime as it had claimed spectacular double digit growth of 10.3 per cent for the year 2010 and after. The 2010 figures were revised to 8.5 per cent in 2015 bringing forward the base year from 2004-05 to 2011-12 by NDA regime.

In a fresh controversy now the working paper of the former CEA presented at the Centre for International Development at Harvard University says that even the 7 per cent growth rate calculated for a period between 2011-12 and 2016-17 is “a significant overestimation”. The new working paper focuses on technical methodological changes which are distinct from more recent GDP controversies such as “back-casting” and puzzling upward revisions for latest years.

The working paper of Arvind now estimates that actual growth may have been about 4½ percent “with a 95 per cent confidence interval of 3 ½ -5 ½ per cent.” The fresh revelations seem to suggest that despite the economic reforms of 1991 India continues to tread the slow growth path which is below 5 per cent. This was derisively described by economist Rajkrishna as “Hindu rate of growth” and has since struck as a characterisation of socialist model of development.

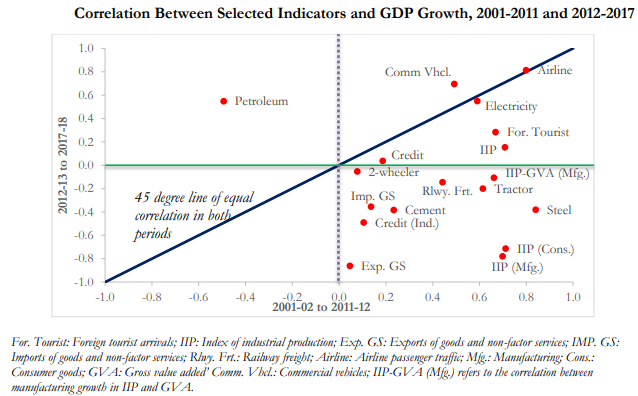

Arvind Subramaniam has put up the evidence in the paper based on disaggregated data from India and “cross-sectional/panel regressions” to lend credence to his claims.

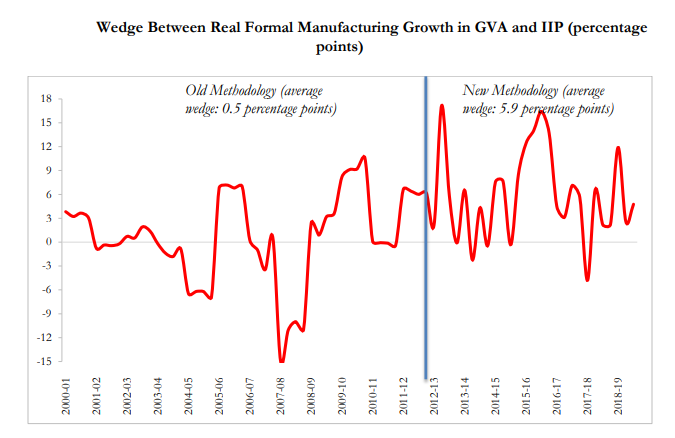

A reason for the “overestimation” according to the author is due to a key methodological change, which had significantly affected the measurement of the formal manufacturing sector. Arvind Subramaniam in an article in Indian Express cautions that the finds should not be construed as “political” but a “technical” exercise carried out by technocrats.

This according to Arvind Subramaniam implies the monetary and fiscal policies were too tight and interest rates were too high by as much as 150 basis points and “the impetus for reform possibly dented”.

These findings now indicate that India’s economic performance was not “spectacular” as it was then believed to be. The paper goes on to look at the possible policy implications that the new dispensation must take up namely that of revisiting the entire national income accounts and use this ‘adversity’ as an opportunity (created by the Goods and Services Tax regime) to significantly improve the economy and restoring growth should be an urgent priority for the Modi 2.0 government.