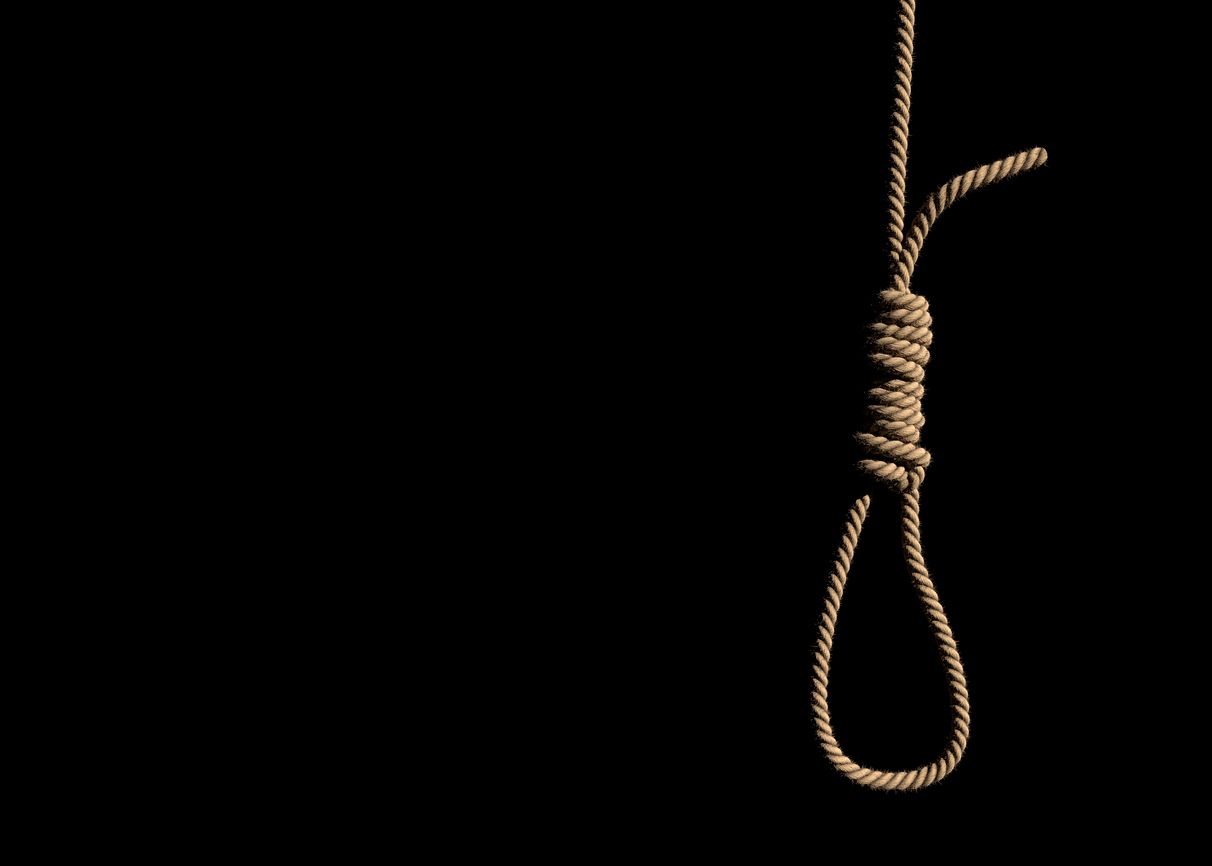

Why the noose, lynch mobs or castration can't root out rape from society

The brutal rape and murder of a veterinarian in Hyderabad has once again renewed the demand for instant mob justice for rapists, among public – lynching and castration being the most-demanded punishments.

Similar demands were made by the public following the horrific rape of a young physiotherapist in what is now known as the Nirbhaya case, in December 2012, in New Delhi.

Speaking at an event, a day after the accused in the Hyderabad gangrape and murder case were shot by the police in an encounter, Chief Justice of India Sharad Arvind Bobde clarified that justice cannot be instant and would lose its character if it became revenge. He, however, did acknowledge that the criminal justice system should be revamped to reduce the time taken to dispose of cases.

Will extreme punishments work?

But what about the demands of death penalty or castration? Retired Chief Justice JS Verma, who headed a three-member committee set up after the Nirbhaya case, has done a thorough examination of the possibilities and feasibility of such punishments.

The committee examined such punishments and other points in great detail when it was asked by the government to look into the criminal system to provide for quicker trial and enhanced punishment for criminals committing sexual assault of extreme nature on women.

Also read: MPs bay for blood, but aren’t cops too guilty for Hyderabad rape?

The other members of the panel were Justice Leila Seth and advocate Gopal Subramamanium. Over the course of a month, the committee spoke to 109 lawyers, students, academics, doctors, police officers, as well as officials in government departments and international institutions, and examined dozens of Supreme Court judgements of various countries.

It came out with a 631-page report which discusses sexual assault, rape, sexual harassment, child sexual abuse, khap panchayats and ‘honour killings’, medico-legal issues, police reforms, education and perception reforms and electoral reforms.

The panel noted that over the years, courts in India have consistently held that sexual offences should be dealt with more sternly and undue sympathy to impose inadequate sentence would do more harm to the system and undermine public confidence in the efficacy of law.

The committee examined in great detail various Supreme Court judgements in India and the rationale for a particular punishment and why judges have generally rejected the death penalty. The committee recommended that the minimum punishment for rape be enhanced from seven years to 10 years and that the legislature clarify that life term means staying in jail till the end of natural life of the convict and does not mean release after 14 or 20 years.

Death penalty, a step backward

Indian laws restrict the death sentence to the ‘rarest of the rare’ cases. “The committee summed up various judgements to consider three points to arrive at the ‘rarest of rare case’: the gruesome nature of the crime; the mitigating and aggravating circumstances in the case; and whether any other punishment would be inadequate. The court must satisfy itself that death penalty would be the only punishment which can be meted out to the convict.

In cases of gangrapes or those where the victim is left in a vegetative case — for 36 years as in the case of nurse Aruna Shanbhag — the committee felt that the death penalty could be given only if the “intention to kill” is categorically established. Often it is not.

Also read: Hyderabad exposes hypocrisy of the angrier-than-thou like Jaya Bachchan

“In our considered view, taking into account the views expressed on the subject by an overwhelming majority of scholars, leaders of women’s organisations and other stakeholders, there is a strong submission that the seeking of death penalty would be a regressive step in the field of sentencing and reformation. We, having bestowed considerable thought on the subject, and having provided for enhanced sentences (short of death) … in the larger interests of society, and having regard to the current thinking in favour of abolition of the death penalty, and also to avoid the argument of any sentencing arbitrariness, we are not inclined to recommend the death penalty,” the report read.

Needed: Gradation of offenders instead

The committee suggested that sex offenses be graded. For instance, in many cases, the survivor is able to eventually overcome trauma and lead a normal life, with the help of society and medical care. In such cases, the injury to the person may not warrant punishment with death. The committee went into great detail over international covenants on the death penalty and noted that some 150 countries had done away with the death penalty and there was an increasing shift towards abolishing the death penalty altogether.

The committee noted that “there is considerable evidence that the deterrent effect of death penalty on serious crimes is actually a myth”. The Working Group on Human Rights had found that the murder rate has declined consistently in India over the last 20 years despite the slowdown in the execution of death sentences since 1980. Instead, the committee favoured enhancement of punishment to imprisonment for the rest of life, without any parole.

Castration against ‘human rights standards’

Many people, especially on social media, have demanded castration of the accused in rape cases. The committee noted that chemical castration that reduces the libido of males, requires constant monitoring and includes large-scale side effects, such as osteoporosis, hypertension, fatigue, weakness, weight gain, nightmares.

Also read: When will we go beyond drama to end rapes?

“We are further of the opinion that chemical castration fails to treat the social foundations of rape which is about power and sexually deviant behaviour. We therefore hold that mandatory chemical castration as a punishment contradicts human rights standards.” Similarly, it rejected calls for permanent physical castration, as physical mutilation of the body (other than in the death penalty) is not recognised by the constitution.

(The author is a journalist with 40 years of experience in the Indian and American print industries)