Simranjit Mann’s Sangrur win is troubling for both Centre, Punjab govt

On March 10, as Punjab gave an unprecedented mandate to the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), many political veterans of the state bit the dust. Amid the electorate’s deafening jubilation over an impending revolution promised by the AAP and the muted dismay of old warhorses from the Congress, Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and the BJP, who had all faced humiliating routs, few paid any heed to the defeat of another candidate who was once among Punjab’s most trailblazing politicians.

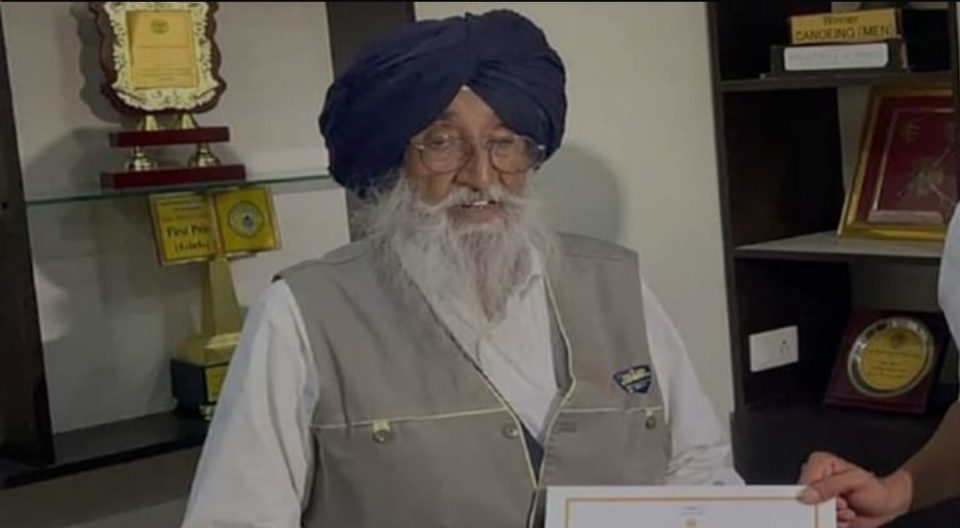

Former two-term Lok Sabha MP and head of a splinter SAD faction, the SAD (Amritsar), 77-year-old Simranjit Singh Mann had contested the Punjab Assembly polls from the Amargarh constituency in Malerkotla district. Like the five assembly polls or the four Lok Sabha elections he had contested since 1999 when he last won as an MP from Sangrur, Mann lost the Amargarh contest too; this time to 59-year-old former professor and AAP candidate Jaswant Singh Gajjan Majra, albeit by a narrow margin of 6,043 votes.

Perhaps none in Punjab would have thought at the time that in just over three months Mann would make an electoral comeback that would, in ways more than one, overshadow the AAP’s historic victory. On June 26, as the controversial Sikh hardliner and strident proponent of a “sovereign state” of Khalistan won his first election in 23 years from Punjab chief minister Bhagwant Mann’s home turf of Sangrur, the veteran leader proved the cliché that a politician must never be written off.

Also read: Simranjit Singh’s Sangrur victory jolts AAP’s Mann in Punjab

His over two-decade-long political wilderness may have made Mann an unfamiliar name to many outside his home state. However, there are ample reasons why his victory in the Sangrur by-poll has set the politics of Punjab buzzing with trepidation and euphoria in near equal measure.

A jolt to Bhagwant Mann

Critics of the ruling AAP see Mann’s by-poll victory as a much-needed jolt for the Bhagwant Mann-led government. The symbolic importance of Sangrur for the AAP cannot be overstated. The constituency had elected incumbent CM Bhagwant Mann to the Lok Sabha in 2014 and 2019. The seat fell vacant after Bhagwant Mann won his debut assembly poll from Dhuri – an assembly segment within the Sangrur Lok Sabha constituency – this March and took over as CM.

Besides Dhuri, the AAP had also won the other eight Assembly segments that form the Sangrur Lok Sabha constituency. Punjab’s finance minister Harpal Cheema and minister for youth and sports, higher education and school education, Gurmeet Singh Meet Hayer are AAP MLAs from Dirba and Barnala seats, respectively, that also fall under the Sangrur Lok Sabha constituency. As such, Mann’s by-poll win against the CM’s handpicked candidate Gurmail Singh is being touted as an unambiguous sign of the electorate’s loss of faith in a CM and party that had come to power three months ago promising the electorate imminent badlaav (change).

Conversely, there are numerous others who prophesize that Mann’s by-poll win could herald ominous times for Punjab; re-igniting a radical, communally charged, violent and separatist politics that the state had taken nearly three decades to put behind but had never fully forgotten. These fears, understandably, trace their roots in Mann’s chequered political past and the politics he has come to symbolize.

Born in Shimla in 1945, Mann comes from a political family. His late father, Lt. Col. Joginder Singh Mann, had served as Speaker of the Punjab Vidhan Sabha in 1967. His wife, Geetinder Kaur, is the sister of Patiala MP Preneet Kaur, wife of former CM Amarinder Singh.

Simranjit’s political journey

Yet, politics wasn’t Mann’s first calling. He was commissioned in the Indian Police Services in 1967 and had gone on to serve in various capacities in the Punjab Police and the CISF until 1984 when he quit the IPS in protest against Operation Blue Star. It was then that Mann, a self-proclaimed follower of Khalistani separatist Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale who was killed by the Indian Army in Amritsar’s Golden Temple during Operation Blue Star, began exploring life in politics.

A vocal proponent of Khalistan and a vociferous critic of Delhi, Mann founded his own SAD faction – SAD (Simranjit Singh Mann), now called SAD (Amritsar) – and put-up candidates in the 1989 Lok Sabha polls. Mann had been in jail for the entirety of the poll campaign, booked for various charges. However, his newly formed party wrested six of Punjab’s 13 Lok Sabha seats – Bathinda, Faridkot, Ludhiana, Ropar – with Mann too winning from Tarn Taran in absentia. Three other independent candidates who won that election from Amritsar, Ferozepur and Patiala were also said to have had Mann’s backing.

In Mann, Punjab politics had found a new stormy petrel – a man who promised to pursue the separatist cause of Khalistan and never compromise on the interests of his community or the teachings of his faith. That he wasn’t bluffing like most politicians often do became clear soon afterwards. Though he was released from prison after being elected an MP, Mann refused to enter the Lok Sabha for its proceedings because Parliament’s security protocols didn’t allow him to attend the sessions while carrying his kirpan (a dagger that devout Sikhs carry on their person as an article of faith). Mann resigned from his seat in protest.

The electoral triumph of his fledgling party didn’t last very long. As his party began to wither across Punjab in subsequent years, Mann chose a new constituency, Sangrur, for himself but lost his re-election bids to the Lok Sabha in 1996 and 1998 as well as to the Punjab assembly in 1997. The personal defeats and the challenges to keep his party afloat in the face of repeated drubbings, notwithstanding, Mann soldiered on.

Then in 1999, a decade since his first Lok Sabha victory, Mann was back to Parliament as the MP from Sangrur, defeating SAD’s Surjit Singh Barnala to whom he had lost his re-election bids in 1996 and 1998. But the Simranjit Mann who won in 1999 was, some believe, more pragmatic or even conciliatory than the man who had won from Tarn Taran a decade ago.

Though he still spoke for the same causes and with the same passion, Mann made no fuss over being told, once again, that he couldn’t enter Parliament carrying his kirpan. However, this seemingly wiser version of the mercurial Sikh hardliner did not endear him to the voters and the downslide of his party and his own politics continued.

In the 2004 Lok Sabha polls, Mann finished third in the electoral contest from Sangrur, well behind the winner, SAD’s SS Dhindsa, and runner-up, Congress’s Arvind Khanna. From then on, for 23 years, Mann struggled to stay politically relevant. He fought the Lok Sabha polls from Sangrur in 2009, 2014 and 2019, only to lose and even forfeit his deposit each time. The SAD (A) and Mann faced a similar fate in successive Punjab assembly elections between 1997 and 2022.

Yet, in all these years, those close to Mann insist, he stubbornly stuck to the issues he had originally based his politics on, refusing to re-invent himself or re-model his rhetoric to keep up with the changing political landscape of Punjab or the aspirations of its electorate.

AAP’s missteps

And then last week, Mann bounced back, winning Sangrur once again. The general perception over Mann’s victory, however, is that it was triggered not so much because of his own popularity but due to the circumstances created by the ruling AAP over the past three months, which tilted public perception, particularly among panthic voters, towards a politics espoused by the 77-year-old.

The 108 days of AAP regime in Punjab have been characterised by the party’s failure to understand the state’s syncretic and social fabric as also its incompetence in dealing with emotive issues such as the sacrilege cases of 2015, the continued incarceration of Bandhi Singhs (Sikh prisoners languishing as undertrials across Punjab prisons) and threats to internal security.

The AAP got off on the wrong foot within a fortnight of winning Punjab when it chose ‘outsiders’ and businessmen parachuted by the Delhi leadership of Arvind Kejriwal as the party’s Rajya Sabha nominees. Many saw this as an affront to Punjabis and AAP’s political rivals launched a united offensive against Bhagwant Mann and Kejriwal on the issue. The AAP chose to brazen the storm and hoped that its populist announcements – free electricity, anti-corruption helpline, et all – would level out any disaffection among voters.

However, the party, in its overzealousness to gain easy publicity, spent massive amounts from the already debt-ridden exchequer on advertising its announcements in states such as Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh where AAP is eying an electoral expansion later this year. Over Rs 13 crore was spent by the AAP government on full-page newspaper advertisements within two months of coming to power and the state was also, reportedly, footing the bill for Kejriwal and Bhagwant Mann’s joint political campaigns beyond Punjab.

The AAP perhaps did not realise that its antics were proving the opposition’s charge of Bhagwant Mann acting as a rubber stamp CM to his Delhi counterpart and reducing Punjab to a satellite colony of AAP’s Delhi government. Kejriwal summoning meetings of Punjab bureaucrats and Mann dashing to the national capital at a drop of a hat for frequent meetings with his party boss strengthened this perception, creating palpable disillusionment among voters who had, three months back, rejected legacy parties for AAP in the hope that Bhagwant Mann’s regime would prioritise Punjab and Punjabiyat over his party’s political interests.

Veteran journalist and former AAP MLA Kanwar Sandhu told The Federal that the undeniable takeaway from the Sangrur by-poll result is people wanted to teach the Mann government a lesson. “Mann must do some soul searching otherwise problems are set to mount for him,” Sandhu said.

Another senior journalist, Devinder Pal, said that public anger against the CM aside, people have also begun to get disillusioned with local AAP MLAs who “were inaccessible even to their party supporters”.

While the CM’s ready willingness to play second fiddle to his Delhi counterpart chipped away at the favourable public perception AAP had built before the assembly polls, administrative and security lapses across the state brought an even bigger electoral challenge for the state government.

In a state that still recalls in fear the dark days of militancy during the 1980s, internal security has always been an emotive plank for Punjabis. On this score, the AAP’s report card of the past three months appears to be tainted wholly in red. From communal clashes in Patiala to a rocket-propelled grenade being hurled at the Punjab police’s Intelligence headquarters in Mohali and the many daylight murders – including, most famously, of Punjabi singer and budding politician Sidhu Moosewala – by trigger-happy gangs, the past three months have been an internal security nightmare for Punjab and portrayed the AAP regime as manifestly incompetent with regards to law and order in the border state.

A warning to Badals

The Sangrur by-poll result was the sum of all these problems that AAP had brought upon itself. Simranjit Mann effectively used the growing resentment against the ruling party to marshal support for his campaign. That it was the SAD (A) chief who defeated AAP and not a candidate from the Congress, SAD or the BJP also shows that these principal opposition parties had yet to recoup from the jolt they faced in March and, more importantly, that there was a renascent resonance for the radical extremism and Sikh identity politics that Simranjit Mann symbolises.

Of particular significance here is the likely impact of the Sangrur by-poll result on the Sukhbir Badal-led SAD in Punjab, which vies for the same panthic space that the SAD (A) chief represents. The political consensus across Punjab seems to be that Mann’s Sangrur victory was ensured because the panthic vote, which the Badal-led SAD commanded for a long time, had consolidated solidly behind the SAD (A) chief this time. This shift happened despite the Badals fielding Kamaldeep Kaur Rajoana, sister of Balwant Singh Rajoana, a death-row convict in former Punjab Chief Minister Beant Singh’s assassination case. The SAD’s choice of Bibi Rajoana was a clear bid to reach out to the party’s panthic vote bank but it failed remarkably and she ended up in fifth position with a mere 44,428 votes.

Sandhu points out that Simranjit Mann’s campaign was dominated by panthic issues such as justice in sacrilege cases and freeing of Bandhi Singhs. Sandhu believes that with Mann’s victory, these issues along with emotive matters such as river water sharing disputes between Punjab and Haryana, transfer of Chandigarh and other Punjabi speaking areas to Punjab will take centre stage. These were all matters that the Badal-led SAD tried to monopolise in the past, along with its control over the influential Sikh Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee, a Sikh body responsible for maintaining gurudwaras, including Harmandir Sahib or the Golden Temple.

“The Badal-led SAD will be under tremendous pressure in running the affairs of SGPC. Those opposed to the Badal family and their control of the SGPC have become empowered after Simranjit Singh Mann’s victory,” says Sandhu.

Also read: Sukhbir Badal-led Akali Dali’s control over SGPC weakens after Sangrur rout

An alarm of caution

Sandhu believes that Simranjit Mann has mellowed down over the years and is now a more pragmatic and wise politician than how he had started off. However, there are enough number of people who fear that the pro-Khalistan leader’s by-poll victory should sound an alarm of caution. Though several of AAP’s political rivals hailed the Sangrur by-poll result as a much-needed reality check for the ruling party, there were also those like Congress leaders Manish Tewari and Randeep Surjewala who cautioned against “other implications” of the by-poll result and forewarned that “Punjab can’t be pushed back in the blind alley of violence and terrorism”.

The SAD (A) chief, who describes himself as someone “striving for Khalistan” even in his Twitter bio, gave enough reasons for people to be wary of his victory and the political churn it is likely to trigger in the restive state. He credited his win to the “teachings that Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale has given”. That one reaction from Mann alone should worry Punjab and the rest of the country too – and it should make AAP and its leadership in Punjab as well as Delhi take a long hard look at what direction they are pushing the border state to.

(The writer is a journalist based in Chandigarh. He tweets at @journoviv)