Hidden meanings and unspoken truths: A 360 degree view on the language row

Tamil Nadu politicians have risen as one voice against the “Three Language Formula” recommended by the Draft National Educational Policy (NEP) 2019. They feel it is an attempt to impose Hindi on non-Hindi speaking states through the back door.

The Draft 2019 says “Three Language Formula, followed since the adoption of the NEP 1968, and endorsed in the NEPs 1986/1992 as well as the National Curriculum Framework 2005, will be continued, keeping in mind the Constitutional provisions and aspirations of the people, regions, and the Union.”

Lingual exchange, the initial idea

Originally, under the Three Language Formula, it was decided that in Hindi speaking areas Hindi would be taken up as first language followed by teaching of English as an associate official language. The third language it was decided would be “any local language.” This could mean Assamese, Bangla or even Tamil.

In the non-Hindi speaking regions the order was local language, followed by English and Hindi. It was expected that this formula would ensure better integration of India as children from Hindi speaking areas would learn an additional local language from other regions and those from non-Hindi speaking areas would learn Hindi. The policy was followed more in breach. Many Hindi speaking states introduced Sanskrit as the third language and states like Tamil Nadu restricted themselves to the two language formula. But there were no restrictions upon private schools to teach Hindi as the third language.

States like Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka did introduce three language formula in schools. But Tamil Nadu and the rest of India which includes all the northern states defied the policy. Perhaps the policy makers were too dreamy or romantic to imagine that students from Haryana or Punjab would learn Tamil or Telugu as the third language.

The policy, however, has a provision where if 40 or more children wished to study in their mother tongue other than the state language, they should be provided such an instruction. Due to this relief, regional educational bodies in Delhi such as Andhra Association and Delhi Tamil Education Association run schools that are able to teach students in their respective mother tongue.

A minority tongue, but indispensable

To understand the current controversy, we need to look into history. The Radhakrishnan Commission Report of 1948 which forms the basis of language policy in India had observed that modern standard Hindi itself was a minority language and had no superiority over others such as Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, Marathi, Bengali, Punjabi, Malayalam and Gujarati – all of which had a longer history and greater body of literature. Despite this the Commission felt that in later years Hindi would eventually replace English as the means by which every Indian state may participate in federal functions.

There is no national language in India. Instead there are 22 official languages. Hindi was decided as medium of communication along with English for the Union Government. The states were given liberty to decide upon their own official language.

Though the language formula is more than seven decades old the problems still remains. English is still a preferred language in India for securing better jobs. While many aspirational Indians are struggling to master the language for achieving better employability and higher education, there is hardly any growth of regional languages.

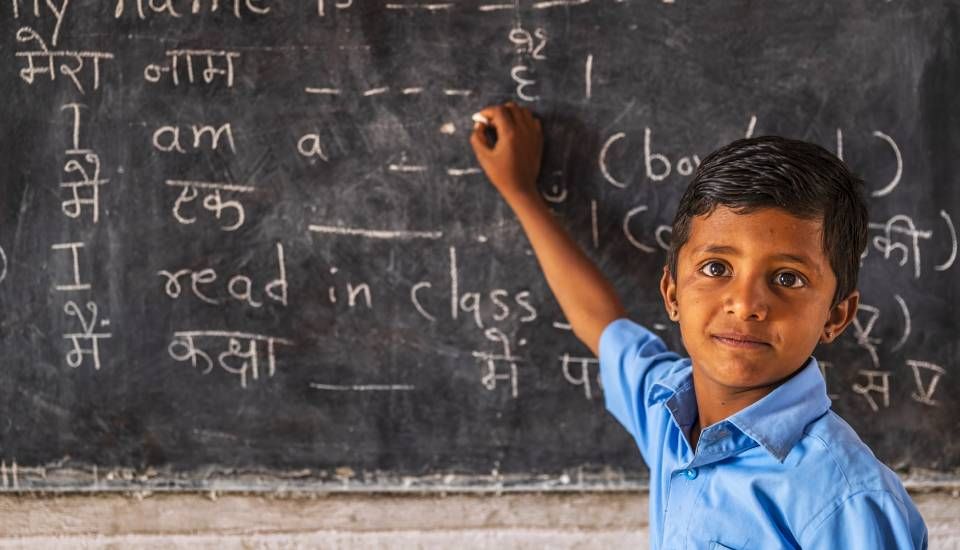

The challenge is to keep parochial demands away and allow the growth of the mother tongue. This is because innumerable studies have shown that students who have had early education in mother tongue perform better in academics. Also children who learn multiple languages from childhood have higher learning capabilities.

Rise of Hinglish

But the basic fact is that Indian languages including Hindi have hardly grown. If one were to go by popular culture, Hindi influenced by Bollywood is going Hinglish, a mix of English words with Hindi. The debate between pure Hindi and Hindustani which would have had traces of Urdu is already lost. Many Hindi newspapers and news channels are happily embracing Hinglish as they find it a more effective medium of communication.

In Tamil Nadu, the state government in its efforts to promote Tamil even introduced it in higher education. For instance, engineering courses were offered in Tamil and those who opted for it are actually struggling to get meaningful employment.

What makes Tamils wary?

Despite these setbacks, language will continue to remain a political hot button, especially in a state like Tamil Nadu. Tamil, like Sanskrit, is a classical language and is unique in the sense that it is used deftly by politicians in their ordinary communication with the masses. Leaders of Dravidian movement such as the late Karunanidhi are known scholars of the language and they had used it to create a political identity.

The Draft NEP 2019 says the “Three Language Formula needs to be implemented in its spirit throughout the country, promoting multilingual communicative abilities for a multilingual country. However, it must be better implemented in certain states, particularly Hindi- speaking states; for purposes of national integration, schools in Hindi- speaking areas should also offer and teach Indian languages from other parts of India.”

This hasn’t satisfied Tamil Nadu politicians as they do believe that this could only be a ploy to push Hindi forcibly down the throats of Tamils.

Similarly, in November 1990, there were howls of protest from the South when the then Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh Mulayam Singh Yadav had called for banning English from the nation.

In 2014 there were protests when Narendra Modi 1.0 issued a circular saying priority should be given to Hindi over English while communicating its decisions through social media such as Twitter and Facebook.

The then NDA allies and the DMK had blasted Sanskrit Week celebrations in Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) schools on the Centre’s directives. The then Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, J Jayalalithaa, had asked the Prime Minister to modify the order and honour classical languages instead. She was reacting to a letter sent by the Union ministry of human resource development to state chief secretaries asking them to celebrate Sanskrit Week.

Row over Sanskrit

Another controversy arose in Modi 1.0 when the Centre told the Supreme Court that Sanskrit will be the compulsory third language from Class VI to Class VIII in Kendriya Vidyalayas. The Centre had then said that the decision follows an agreement between KV Sangathan and Goethe Institut-Max Mueller Bhawan in 2011 and the decision did not involve the HRD ministry.

In 2014, Sanskrit Bharati, an organisation affiliated to the RSS, insisted that Sanskrit be taught in place of German in schools and they had begun their campaign with the Kendriya Vidyalaya schools.

All these developments were read by Southern states as the sneaking in of Sanskrit through the backdoor and violative of the government’s own “Three Language Formula” as there were fears that regional languages would be replaced by Sanskrit across the nation including Hindi speaking regions.

Reality check

The truth is the Three Language Formula was never honestly or imaginatively pursued all these years either by the Centre or by the state governments, especially those in the north. Irrespective of whether it was the Congress-led UPA regime or BJP-led NDA regime, the same attitude prevailed.

The makers of the Indian Constitution had arrived at the Three Language Formula as an equitable solution after many rounds of deliberations. The British had evolved an education system based on English which, according to eminent historians, had two fallouts. One, it widened the gap between the educated and the masses, and, secondly, it stunted the development and growth of Indian languages.

The language debate is therefore caught in inaction or its extremities. If successive Congress governments at the Centre are guilty of not being honest about implementing the language formula, neither the BJP now seems to be a knight in shining armour. Dravidian politicians of south see it as another attempt at pushing the Hindutva agenda.