- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

HIV +ve babies could do a U-turn and test negative

A baby's HIV status can change until it is 18 months old, as new research has found. Seven-month-old Kalai, who tested +ve, could see a different result.

Seven-month-old Kalai (name changed) tested HIV +ve. Her mother is severely mentally retarded and has no idea about her daughter’s father. As the mother convalesces in a home run for destitute women, Kalai is in the safe custody of Anandha Illam, a unit of Community Health Education Society (CHES) run by Dr P Manorama. Kalai was sent there after the mother was rescued by police and...

Seven-month-old Kalai (name changed) tested HIV +ve. Her mother is severely mentally retarded and has no idea about her daughter’s father. As the mother convalesces in a home run for destitute women, Kalai is in the safe custody of Anandha Illam, a unit of Community Health Education Society (CHES) run by Dr P Manorama. Kalai was sent there after the mother was rescued by police and social workers from a prostitution racket.

Anandha Illam, which means ‘abode of happiness’ in Tamil, is Kalai’s refuge for now and possibly for many years to come. P Muthupandian, who is in charge of the home, explains that it all depends on the HIV test that will be carried out after Kalai turns 18 months old, when a definitive result of her HIV status can be ascertained. The staff at the home hopes that she tests negative, as the home in coordination with government agencies will ensure that they find her another, more permanent home — either through adoption or, in some cases, foster care.

The home is the brainchild of Dr Manorama, a paediatric gastroenterologist and former chairperson Child Welfare Committee, Chennai. It is a unit of CHES, which was started on a small scale in 1993. Children infected with HIV or babies who have been abandoned because of their HIV status are sent here through child welfare committees or cradle baby schemes in various districts. The ones who have been diagnosed with HIV after 18 months, when it can effectively confirm the infection, are retained here for treatment and stay on till they continue their education. Those that test negative are given up for adoption. So far, in the past 25 years, at least 57 kids have been adopted by families, while some infected children have died due to the disease. Now, the home has 73 inmates — babies, toddlers, teens and adults. The aim is to reintegrate them with society by all means — food, shelter, treatment and education, whatever it takes.

Dr Manorama explains that she began the organisation after she saw the plight of HIV +ve kids when she was a government doctor. Back then, the disease was at its peak and the government was doing everything possible to alleviate fear and advocate prevention and timely care.

“As a doctor in the Institute of Child Health I saw the queer behaviour of people when two children with hepatitis and HIV were admitted at one of the wards. The stigma was so bad that the orphanage they belonged to didn’t want to take them back. So I decided to take care of them and set up the NGO. More children began to get referred to us.” While one of them died, the other survived and is a 30-year-old independent man today, she says.

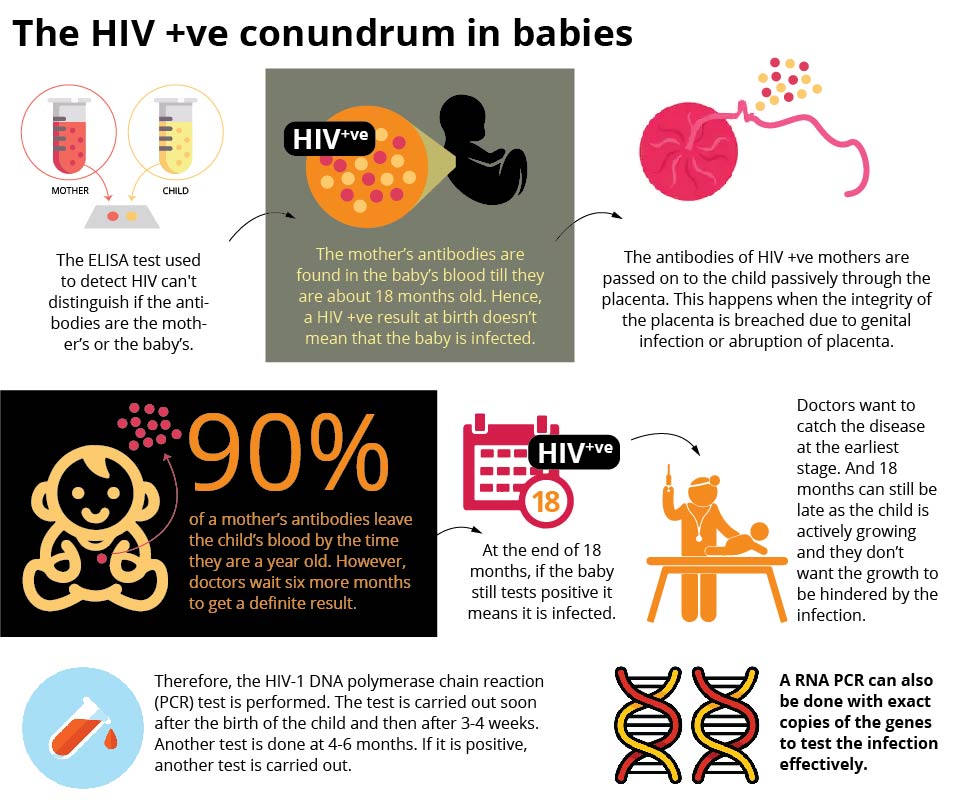

HIV mystery in babies

Dr Amrose Pradeep, chief medical office, YRG Centre, which has been undertaking pioneering work in HIV/AIDS in the country, explains the reasons for the change in diagnosis for a newborn. He says, “The ELISA test cannot demarcate the antibodies (large Y-shaped protein produced mainly by plasma cells that is used by the immune system to neutralize pathogen) as the mother’s or the baby’s till they are 18-months-old. While most of the maternal antibodies disappear within a year, we wait for six more months for the remaining to exit. The baby that tested HIV +ve soon after birth can, therefore, test HIV negative after 18 months.”

In HIV-infected mothers, the placenta can passively transmit HIV antibodies to the unborn child. Adherence to treatment can bring down the levels on infection passed from mother to child, studies have disclosed.

However, diagnosis at 18 months can still be late, says Dr Pradeep, who adds that since the child is growing at the stage, the virus load shouldn’t hinder the growth and it is best to detect it earlier to start treatment. “Therefore, we have the HIV-1 DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, which is carried out soon after the birth of the child and then after 3-4 weeks. Another test is done at 4-6 months. An RNA PCR can also be done with exact copies of the genes to test the infection effectively for an earlier detection,” he says.

The Indian Journal of Public Health has observed that in India, the prevention of parent-to-child transmission and antiretroviral therapy services for HIV-infected mothers and children have rapidly scaled up over the recent years. Yet, more than 90 per cent of the HIV infections in children are the result of maternal-to-child transmission (MTCT). The MTCT rate ranges from 20 per cent to 45 per cent in the developing world.

Social workers say that children infected with HIV are most often abandoned for a number of reasons — stigma, misconceptions about the communicability of the disease and poverty.

Poverty and HIV a double whammy

Dr Manorama says that a large section of the children who are brought to the home hail from poor families. “The disease just becomes an excuse for (poor) parents to give away their babies,” she says.

Muthupandian observes that in such families, the mother barely has a say, and is often overruled by the family and the father’s collective will. Despite several awareness campaigns that have centred around how the disease doesn’t spread through air or by touch, the myths persist, says Dr Manorama.

Over the years, therefore, Anandha Illam has become a sought-after home for such children from several districts in Tamil Nadu. Name the district and you will find inmates from there. “We have more girls, as many as 52, among the 73 inmates, because they are seen as a burden, while boys are sources of extra income,” says Muthupandian.

Home away from home

Anandha Illam moved from Chennai to the current location in Bandikavanur village, Ponneri taluk in Thiruvallur district as it began receiving support from The Emirates Airline Foundation in 2009.

The inmates are from various age groups — newborns to toddlers to 18 and above who undergo higher education in schools and colleges. Muthupandian says that the on-campus school caters to children from the age of five till Class 5, after which they are sent to nearby schools.

“Here, they come under the purview of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, after which only extremely sick and weak children are taught till Class 8. After that, they are enrolled in nearby schools and later they pursue college or vocational course as per their choice,” he explains.

The sprawling campus amid paddy fields is not just home to these children. Rabbits, Persian cats and emus are seen prancing around as children huddle among themselves. The older ones run errands and the younger ones have their siesta, even as some of them stay awake and come up with tricks to disturb a sleepy friend.

A few blocks away is an ITI student and a resident of the home, Ramesh (name changed), who occasionally goes to Erode to visit his extended family. “I just returned after a month’s stay. I like to be with them, but I always miss my home,” he says. Apart from a generous dose of nature’s beauty, the children here take a break from academics with music and fencing.

The children are also encouraged to integrate with the world outside even as they grow fond and used to the environment. Muthupandian says that it is their biggest challenge. “Their poor relative’s house may not have similar facilities and they want to return after just a short stay. But we try our best to show them there is a bigger world beyond Anandha Illam and it is worthy of being embraced. Take the case of Ramesh, who with his skills can get as much as ₹30,000 outside. But he insists on being employed here as a gardener for as less as ₹7,000,” he says.

So far, 57 of the children who were tested negative later have been given up for adoption. “We believe that they deserve to live in families. Even for those who grow up here as they are confirmed to be infected with HIV, we stress on the need to start living on their own, once they start earning,” Dr Manorama adds.

Foster care can be tricky

In the early 2000s, two slum dweller women had come forward to provide foster care for two HIV +ve toddlers from the home. “When it was time to test them again at 18 months, the families said they didn’t want to. They feared that if they tested negative, the children will be taken away from them and sent for adoption,” she says, observing that emotional attachment mars the purpose of foster care, which is temporary care.

Muthupandian, who decided to care for one of the girls who got attached to him, explains the bond even better. “She wouldn’t go to sleep without seeing me during nights. It was then that I decided to adopt her. I have a biological daughter too, but she is special to me and I don’t have the heart to tell her to be on her own, now that she is more than 18. In fact, in my family, she enjoys more love than my own daughter. My extended family, including my parents, my wife’s parents and my siblings, have been supportive,” he says.

Hope for better quality of life

The wonder drug that cures HIV may still be elusive, but the quality of life for those under treatment is definitely better, says Dr Pradeep, explaining why cure is still far from reach.

“Once the virus enters the body, it attacks the lymph nodes that protect the body from infections, apart from the bone marrow and the central nervous system. Though the virus can be eradicated, the genetic material is still there in the system and the virus can make copies from it,” he says.

“At the moment, we have a functional cure — which makes it as good as HIV –ve. The moment they go off medication, it comes back. The efforts, therefore, in the field is focused on eradicating the pro-viral DNA of the virus in the system. The drug called Dolutegravir is turning out to be safe, tolerable and very powerful,” he says.

In almost three decades of the journey, better treatment options have increased the life span. “It used to be less than 10 years, and then it went up to 15 and now, it is beyond 25 years. It becomes all the more important for us to make them (the kids) step out of their comfort zone after they complete their education and begin to work.”

The children here are told about their HIV status when they are 12 years old. “They know that they need medicines and care and understand why they need it. As they grow older, they know from the posters and the conversations in the ART centres that they have a disease. So we tell them how they can cope with it and also touch upon topics like whom they should marry and life in adulthood,” says Dr Manorama.