- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Tiger conservation doesn't need eviction of tribals

Without the tribal people’s support, tiger conservation cannot be achieved, and so dialogues need to continue rather than evicting locals, and the community participation initiatives and tiger numbers are proof of that.

For Bellaiah in Chikkayelchetty village, his 20 cows and 30 sheep are his life. Besides the milk from the animals, the cow dung that he sells to tea estates nearby is the main source of his income. But the villager staying near Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Gundlupet taluk of Karnataka’s Chamarajanagar district is under constant threat from tigers. In fact, he had lost about four cows to...

For Bellaiah in Chikkayelchetty village, his 20 cows and 30 sheep are his life. Besides the milk from the animals, the cow dung that he sells to tea estates nearby is the main source of his income.

But the villager staying near Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Gundlupet taluk of Karnataka’s Chamarajanagar district is under constant threat from tigers.

In fact, he had lost about four cows to tiger attack four years back and was at a loss on what to do.

“The Mariamma Charitable Trust has been a great blessing for me. They came and helped me find the kill and gave me compensation. It made a big difference,” he said, according to the website of the trust.

By giving an immediate, small and interim compensation, the trust was able to resolve the loss of the villager.

This is an initiative that the trust has been carrying out for quite some time.

Sunita Dhairyam, founder of the trust, recalls that they began the initiative after she came to know about the difficulties faced by villagers.

“This is just an interim relief before receiving the compensation from the forest department,” she says, but adds that it has stopped the retaliatory killings of big cats by the villagers, by helping them deal with loss and frustration.

“The WWF India helps MCT with this interim relief fund and it is because of them that we have been able to extend our scheme to the whole of The Bandipur Tiger Reserve and now we will be working in The Nagarhole Tiger Reserve. We also help in Mudumalai to some extent,” says Dhairyam.

Similar initiatives have caught up elsewhere too. The ‘Wild Seve’ (‘seve’ in Kannada means ‘service’ or ‘to serve’) designed by Krithi K Karanth of the Centre for Wildlife Studies (CWS) in Bengaluru, is another example where it has increased the efficiency of the compensation process.

Under the programme launched in 2015, a toll-free helpline, advertised throughout the landscape allows farmers and locals near forests to contact the project for compensation in case of incidents with tigers. Trained field staff are dispatched to the site and document the case.

“The programme has grown to help file more than 15,000 compensation cases so far. Wild Seve addresses the issues of illiteracy, lack of awareness of compensation programs, inability to navigate the government process, and inherent transactional costs faced by people,” says Karanth.

“Live monitoring and response have enabled us to identify locations where repeated losses or encounters have taken place. For families experiencing repeat depredation incidents, Wild Seve has built several predator-proof livestock sheds,” she says.

Rising tiger numbers

The MCT and CWS’s initiatives are an extension of community building measures taken up by NGOs in the wake of rise in human-animal conflict in forests and tiger reserves as a result of an increase in tiger numbers.

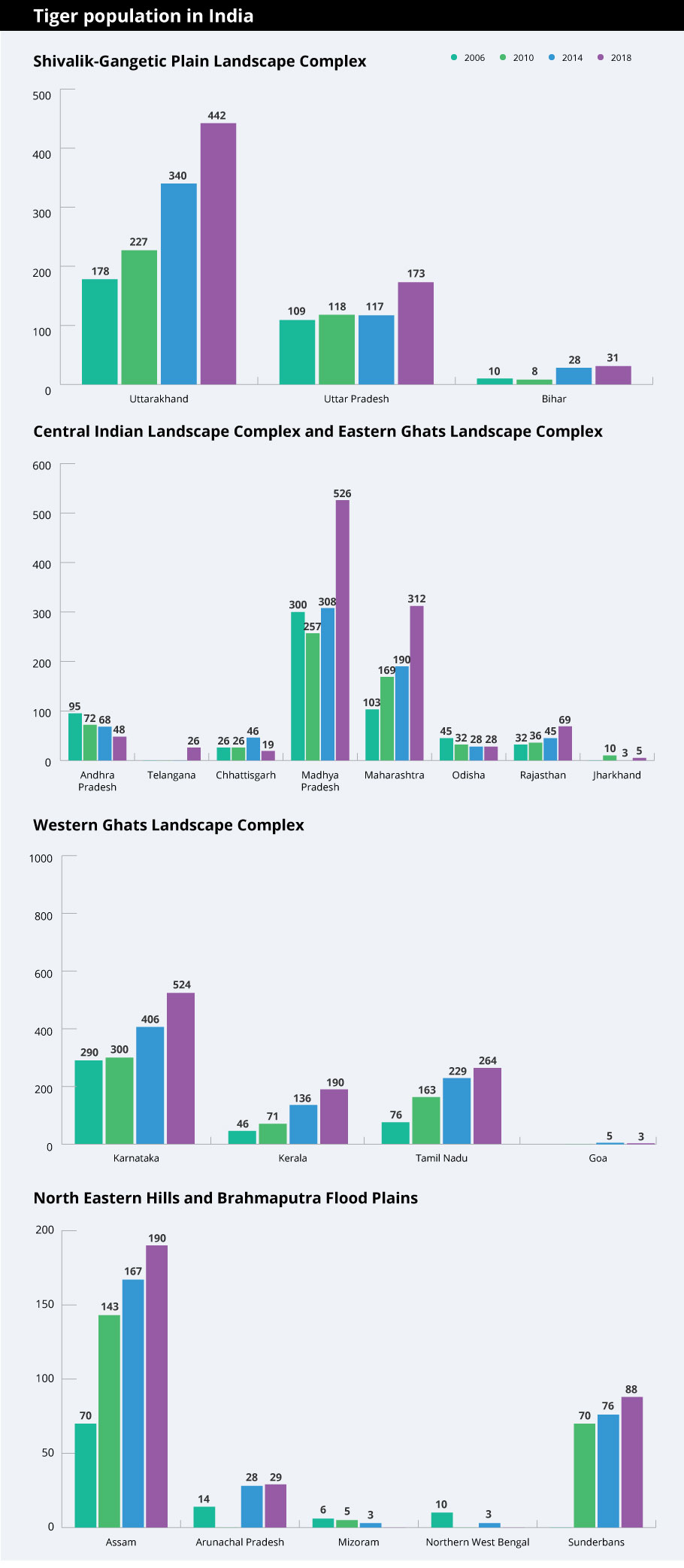

The latest Tiger Census 2018 report shows a 33% increase of the feline’s estimated numbers to 2,967 from 2,226 in 2014 across the country and has almost doubled in 12 years, from 1,411 in 2006.

The highest increase was in Madhya Pradesh with 218 new big cats being counted as of 2018 from four years ago, taking the state’s total to 526. It was followed by Maharashtra, where 122 new tigers took up the state’s tally to 312 in the same four years. Karnataka had the third highest increase of 118 tigers from 406 earlier.

According to a PTI report, an estimation in the reserves showed Jim Corbett National Park having 231 tigers. The Bandipur, Nagarahole, BRT Hills, Wayanad, Mudumalai and Sathyamangalam Tiger landscape spread across the three states of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu together are reported to have the single largest population of tigers in the world (Jhala et al, 2011).

The survey, using 26,838 camera traps that took 34.85 million photographs, and covering 121,337 square kilometres, besides a foot survey of 522,996 kilometres, also made it to the Guinness Book of World Records.

The rise in tiger count has also meant the need for more space, and this is where communities living in and around forests for generations have come under threat of either the tiger, or as its result, displacement from the areas.

Forest distancing

As with everything else, in June this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had hailed the rise in Asiatic lion population living in Gujarat’s Gir forest, in the past five years — from 523 in 2015 to 674 in 2020.

“This is powered by community participation, emphasis on technology, wildlife healthcare, proper habitat management and steps to minimise human-lion conflict. Hope this positive trend continues!” he had tweeted.

Over the last several years, the Lion population in Gujarat has been steadily rising. This is powered by community participation, emphasis on technology, wildlife healthcare, proper habitat management and steps to minimise human-lion conflict. Hope this positive trend continues!

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) June 10, 2020

However, his statement belies the ground realities. In several forests and tiger reserves, activists and local people have complained about the displacement of residents from buffer zones by officials who said it was for reducing human-animal conflict.

As many as 27 petitions were filed in Jabalpur High Court, Madhya Pradesh, in August 2019 against the forcible eviction of tribals from buffer zones of Panna Tiger Reserve as far back as 2009. Most residents complained of loss of land and related farming livelihood.

Similar incidents were reported from various other reserves too, such as the Sariska Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan and Similipal Tiger Reserve in Mayurbhanj, Odisha.

In 2014, around 450 families from indigenous Baiga and Gond communities were evicted from their homes around the Kanha Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh.

In April 2017, 156 families were evicted from Thatkola and Sargodu Forest Reserve in Karnataka while about 1,000 Bodo, Rabha and Mishing tribal community people were moved out from Orange National Park, Assam.

In February 2019, the Supreme Court had asked 16 states to evict Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers from forest land, rejecting a staggering 11.8 lakh claims by residents over their land rights. The order was however stayed later after intervention from the Union Tribal Affairs ministry.

“It has been estimated that 50 per cent of protected areas worldwide have been established on lands traditionally occupied and used by tribal people,” Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, has said.

In the eye of the tiger

However, activists argue that tigers can be conserved and human-animal conflict reduced through community participation initiatives, which provide mutual benefit to the reserves and the local communities.

Manohar Chowhan, member of Campaign For Survival and Dignity, has pointed to the community-led efforts in the conservation of blackbuck in Ganjam district of Odisha, saying from 573 in 1990, its numbers grew to 4,044 in 2018, according to a report in DownToEarth.

The most significant piece of evidence comes from Karnataka’s Biligiri Rangana Hills (BR Hills), where the Soliga tribe, who were once evicted in 1974 after the government declared the forests a wildlife sanctuary, returned in 2010 following a victory in court. Four years later, the sanctuary, which had been made a tiger reserve, saw tiger numbers nearly double.

This is largely attributed to the community’s traditional knowledge of forests and aversion to conflicts with animals. The Soligas are also reported to worship tigers as the Huliverappa.

“Over hundreds of years, we have successfully mastered the art of co-existing with tigers,” Shivmallu, a Soliga, told VillageSquare.in. “It is we who first tend to sick animals, inform the forest guards of tiger and elephant deaths.”

Linking to the mainstream

But the government or conservationists’ efforts are not always welcomed warmly by locals. Like in Kalakad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve (KMTR) in Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu, where World Bank-funded eco development projects were carried out between 1995 and 2001.

“Since the local communities, who are mostly Kani tribes were afraid of uniformed forest staff, the reserve management was unable to approach the people. It was then that they approached NGOs like us,” says R Mathivanan, founder, Arumbugal Trust, in Tirunelveli district.

“Through folk arts, we were able to reach out to the people and create awareness about conserving tigers. We created forest groups in each village to monitor the forests,” he says.

Each village was given ₹2 lakh as revolving fund, wherein a different person would get about ₹20,000 to take up alternative employment like setting up of eateries, textile shops, etc.

S Mary, a beneficiary in Malaiyankulam village who once used to collect tamarind from the forests, says the scheme was like Manna from heaven.

“Women got loans and bought milch cows, which brought us light in our life” she says.

Savithri, another beneficiary from Servalar village, who was once collecting firewood in the forest, has now become an Anti-Poaching Watcher (APW).

“Many youths benefitted from the project. They were given training in driving and encouraged to continue higher studies. Since we know the forests very well, many women and men were given an opportunity to become APWs. That gave us an identity that was hitherto lacking,” she said.

Right to home

However, forest officials have still not been able to bring some people, especially those of the Kani tribe, out of the forests, although they have been successful in reducing their forest dependency.

A similar issue was seen in Nagarhole where the Mullu Kurumbas and Betta Kurumbas were brought out after the sanctuary was declared a tiger reserve.

“The tribals used to do farming in reserves for their own use. They were never dependent on markets. (When they were brought out of the forests) They were given housing and compensation worth ₹7 lakh. But those tribes were unable to adapt to urban life as their fields were in the forests,” says tribal activist Thanaraj Radhai.

“The tea estates around the reserves employed some of them. They are now taken in jeeps in the morning and dropped in the evening after work,” he says, and pointed out that in Kerala, the government has ensured the tribal rights when Periyar sanctuary was declared a tiger reserve. “But that kind of assurance was not given to the Pulaiyar tribes who were once living in Anamalai tiger reserve in Tamil Nadu,” says Thanaraj.

On the other hand, like the Soligas in BR Hills who fought in court and won back their rights to live in the forests, a number of other tribes are also reclaiming what is truly theirs.

“Sometimes, in the name of tiger reserves, we are forced to leave their settlements, which nowhere comes under the purview of tiger reserves. But with the help of the Forest Rights Act, we were able to get pattas in the last couple of years,” says Parvati Soran, an Irula tribe woman in Coimbatore.

V Naganathan, chief conservator of forests and field director, Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu stresses on the need to have discussions at the individual level and village level.

“We ran a programme called ‘Golden Handshake’, in which if the local communities volunteered to come out of the reserves, they will be given an alternative dwelling and a compensation of ₹10 lakh.

Under another scheme called Pulikutty (Tamil for tiger cub), tribal children are given special classes. And to decrease their dependence on firewood, every tribe house has been given LPG cylinders and the administration supports for refilling too.

Such schemes were implemented in Mudumulai Tiger Reserve and people are now leading a happy life, he says.

The reserve officials say dialogue will continue with the tribes like Soligas, Ooralis and Irulas to come out of the reserve.

“Without the people’s support, conservation cannot be achieved,” said Naganathan.