- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Revolution interrupted: The cult of George Reddy

Nearly five decades after his death, a biopic is now ready on the life and times of student leader at Osmania University, George Reddy.

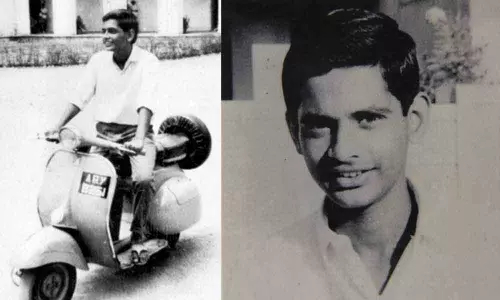

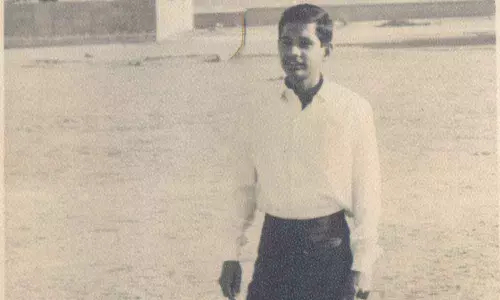

Date: April 14, 1972 Time: Around 4pm Location: Engineering Hostel 1, Osmania University, Hyderabad On the summer afternoon 47 years ago, George Reddy, a young research scholar, walked down the university library, greeting his friends. Wearing a pair of blue jeans, a black and brown striped shirt, a dark brown leather belt and hawai chappals (flip-flops), as author Geeta Ramaswamy describes...

Date: April 14, 1972

Time: Around 4pm

Location: Engineering Hostel 1, Osmania University, Hyderabad

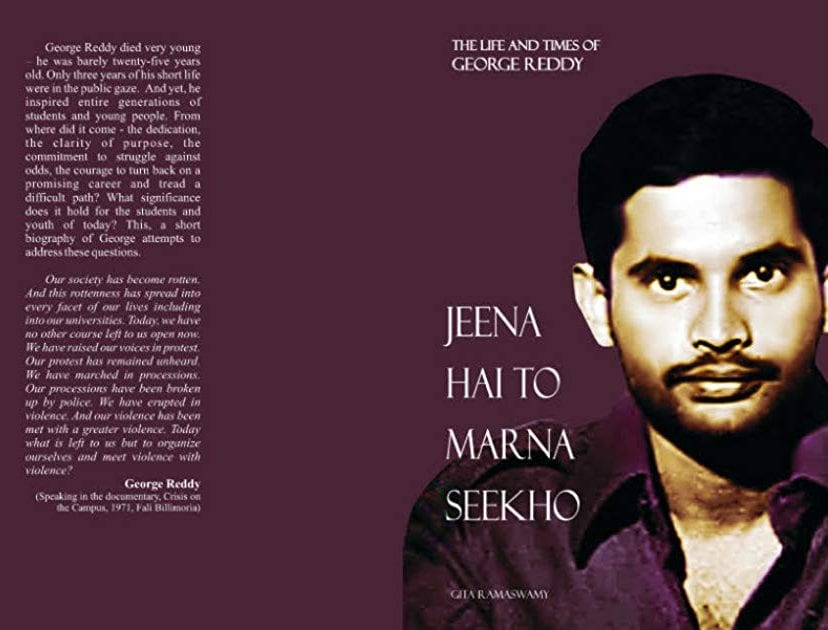

On the summer afternoon 47 years ago, George Reddy, a young research scholar, walked down the university library, greeting his friends. Wearing a pair of blue jeans, a black and brown striped shirt, a dark brown leather belt and hawai chappals (flip-flops), as author Geeta Ramaswamy describes in her book, Jeena Hai to Marna Seekho: Life and Times of George Reddy, he was headed to Engineering Hostel 1.

A little later, his body lay on the staircase of the hostel, a stream of blood gushing down. Stabbed multiple times by a group of assailants — a knife was plunged into his kidney from behind, another into his abdomen, buttocks, and finally one into his heart — George died that day, but continues to live in campus lore.

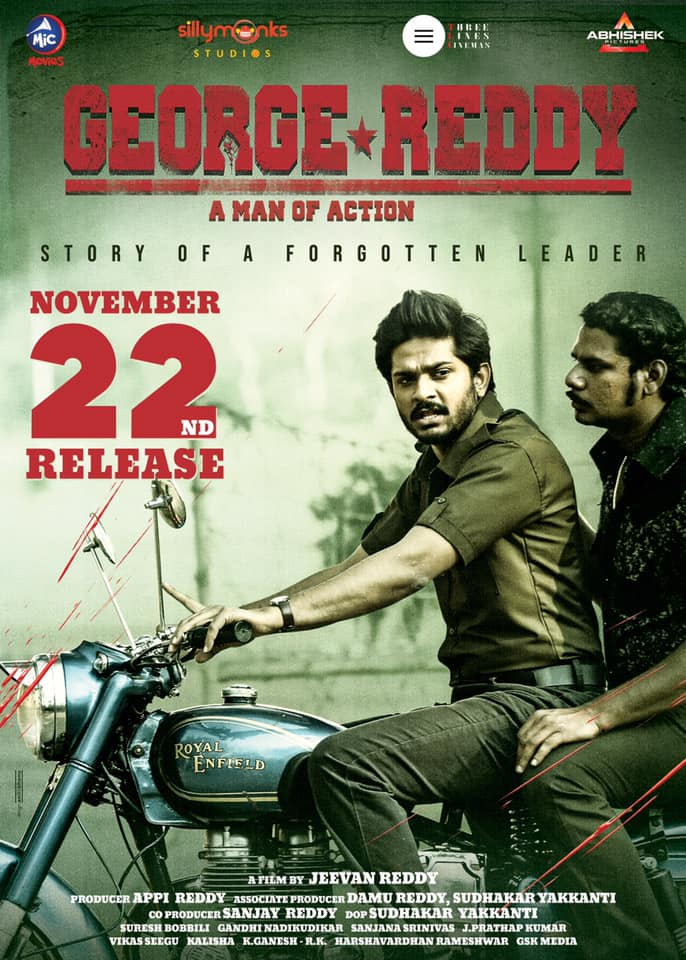

Nearly five decades after his death, a biopic is now ready on the life and times of George. Slated for release on November 22, the movie has created a tremendous buzz, with its trailer garnering over one million views within a week of its release on social media platforms.

But who was George Reddy? A brilliant student, a revolutionary and Osmania University’s very own Che Guevara. According to legend, George was an inspiration to other students because of his deep understanding of social and political issues, both domestic and international, and his empathy for the poor and the disadvantaged. The maverick student leader’s brief, three-year stint at Osmania University left an indelible imprint on the campus politics for years to come.

OU politics

It was a heady era of campus politics with revolutionary fervour in the air and anger in the hearts. The winds of change were blowing across the Osmania University campus in Hyderabad. It was a time when the romance of rebellion was taking roots in the campus, inspired by international movements — anti-Vietnam protests across the United States and Paris students’ revolution.

Into this political milieu entered a young man in his early 20s, with a burning anger over the rotting system and injustices in the society and the restlessness of a revolutionary. Brilliant in academics despite a troubled childhood and a dysfunctional family, he soon struck a chord with fellow students and took up issues of lower-rung staff at the campus with a sense of zeal never seen before.

It did not take the Physics scholar much time to transform from being a shy and studious boy to a charismatic revolutionary. A gold medallist and a boxer, George used to organise debates where he articulated his Marxist worldview and used to advocate “armed revolution” to change the conditions in India.

April 14, 1972, the day he was murdered, changed student politics in Osmania University forever. George, who founded the Progressive Democratic Students Union (PDSU), became a cult figure on the campus and inspired a whole generation of students to take on the virulent right-wing politics.

Troubled childhood

George was born on January 15, 1947 in Palghat, Kerala. His mother Leila Varghese, a Syrian Christian, and father Raghunath Reddy, from Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, had met while pursuing post-graduation at Presidency College in Chennai.

The marriage ran into trouble soon after as Reddy’s family was strongly opposed to it. When George was barely eight years old, his parents separated. Leila had to raise her five children on her own with no help from her husband or his family.

George was 13 when his father passed away. The family was not even informed about his death. George and his siblings moved from town to town as their mother and her elder sister searched for jobs to look after the family and educate the children.

“The harshness of their childhood and the indifference of their immediate families to their plight led George to abhor the discriminations of caste, religion and gender,” says Ramaswamy, who is also a publisher at Hyderabad Book Trust, a not-for-profit Telugu publishing collective.

The biopic

Titled George Reddy with the tagline Man of Action, the Telugu movie seeks to recreate the socio-political situation prevailing in the late 1960s and early 1970s and capture the life journey of the radical student leader who fought for the rights of the underprivileged students and became a hero.

“I was not even born when George was murdered on the campus. I was in my teens when I first heard about the killing and the kind of politics that was responsible for it. His was a truly inspirational life,” director Jeevan Reddy tells The Federal.

George’s zeal, the director adds, left an indelible impression on young rebels across the country.

“I have spent the past five years of my life working on this movie. I have met his family members and friends to know more about him and his struggles,” he says.

Actor Sandeep Madhav, who has a striking resemblance to the student leader, plays George in the film, which is entirely shot on the university campus.

“There are stories of how he used to put blades in a handkerchief and used as a weapon to attack opponents. It took me a long time to master that technique after a lot of practice and bruises,” says Sandeep.

OU — then and now

As captivating as the campus story sounds, the winds of change no longer sweep the OU corridors. The present dynamics of student politics at OU, many former students claim, is completely unrecognisable from the mood that pervaded the campus in the early 1970s.

The tumultuous 1960s, stretching into the early 1970s, was a period when young university students in many developed and underdeveloped countries were conjuring up images of revolution emerging from the mountains and the countryside to the urbanscape.

Now, the “revolutionary zeal” has been replaced by “placement zeal”. The overwhelming concern of the students is the placement status, with the IT industry, of which Hyderabad has emerged as a major hub, being the dream destination for many.

“It is as if the students have become apolitical now. Politics no longer draws their attention. They are more bothered about career prospects,” says S Ramakrishna, a research scholar at the Department of Journalism.

The trend is particularly discernible among the post-liberalisation generation which is aspirational, mobile and ambitious and keen on white-collar jobs, argues senior analyst K Ramesh Babu.

If Che Guevara exerted profound influence on the radical minds of the 1960s generation, it is the success stories of IT startups and the life journeys of young millionaires that beckon today’s youth.

The last time when the 102-year-old university turned into a beehive of political activity was during the Telangana statehood movement that swept the region between 2009 and 2014. The campus became the epicentre of the agitation as students, cutting across political affiliations, joined hands and put up a fight for statehood. Some OU student leaders, who spearheaded the agitation, went on to join the ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) after the formation of the state.

Tumultuous days

In the days when George joined the campus, student elections were hotly contested battles. Having ousted the Youth Congress, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), a right-wing all-India student organisation affiliated to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), was in complete control of political affairs. The campus, many former students recall, was run like a fiefdom. The ABVP wouldn’t tolerate any opposition.

“ABVP exercised all control over colleges, hostels and the campus administration. It did not allow other candidates to contest. If the candidates did not withdraw, they were beaten up,” recalls Ramaswamy, who studied in OU in the 1970s.

“After George’s murder, things were never the same on the campus. Many were inspired to uphold the politics for which he lived and died,” she adds.

The gruesome murder had nationwide repercussions. Scores of MPs, belonging to different political parties, petitioned the then prime minister Indira Gandhi to demand a CBI inquiry into the killing and a ban on the RSS.

“For us, Che Guevara was the icon of socialist bravery. With a striking resemblance, especially the beard, George became our own Che,” recalls Srinath Reddy, a close friend of George who now heads the Public Health Foundation of India.

“As George waded into university politics with fearlessness and a determination to meet violence with violence, and as his small band of radicals challenged the stranglehold of what he called ‘fascist forces’, it was an education for the rest of the student body,” writes senior journalist and author Lata Jishnu in an article.

Known for his opposition to social discrimination and inequality, George drew profound inspiration from the Black Panthers movement in the United States that aimed for racial pride, independence, and equality for all people of Black and African descent. Also, he was inspired by the struggle of Vietnamese people against US imperialism and the peasant revolts in Naxalbari, a village in West Bengal, and Srikakulam in undivided Andhra Pradesh.

“Though I never met George as I joined OU after his murder, he has been a great influence on me and countless other students who were drawn into a new student movement that challenged the establishment. Our lives changed beyond comprehension,” says Ramaswamy.

Another colleague Pradeep Burgula recollects that George had an unwavering commitment to the Marxist worldview and in order to spread and inculcate socialist ideas and ideals, he formed study circles.

“I was a part of one such study circle studying Lenin’s classic, Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism. George once organised a debate on the topic ‘Armed Revolution in India’ in the Science College in which he raised the issue of violence and questioned the colonial mindset of accepting white man’s supremacy even after the end of colonial rule,” says Burgula.

A day after his murder, there was huge outpouring from students. Late in the afternoon on April 15, 1972, around two thousand students took out a procession as cries of ‘Jeena hai to marna seekho’ — a slogan coined by the young leader himself — and ‘George Reddy amar rahe‘ (Long live George Reddy) pierced the still air.

“Jeena hai toh marna seekho,

Kadam, kadam par ladna seeko

Learn to die if you wish to live,

Learn to fight at every step”

The lines continue to inspire his band of followers, though their number is rapidly dwindling on campuses.