- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Ceaseless coal mining turns future black for Gonds in Chhattisgarh

The Parsa coal block, one of 30 in Chhattisgarh’s Hasdeo Arand region, is a step closer from getting environmental clearance. This will be the third mine to open, after Chotia and Parsa East and Kete Basan (PEKB), in what was once a ‘No Go’ area for coal mining in the state. Opening another mine in the core forest area could have deleterious consequences for the people living in it,...

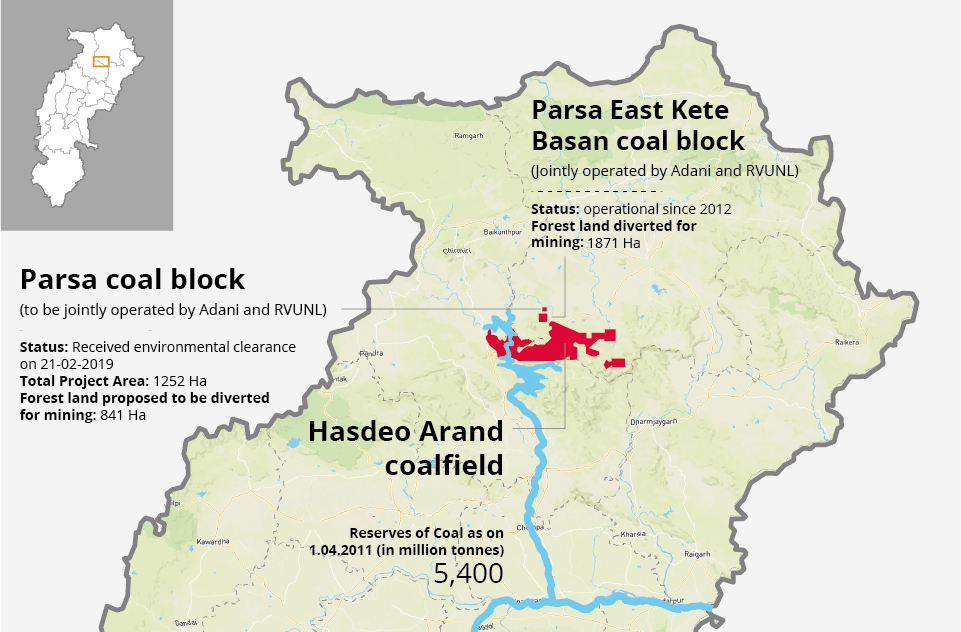

The Parsa coal block, one of 30 in Chhattisgarh’s Hasdeo Arand region, is a step closer from getting environmental clearance. This will be the third mine to open, after Chotia and Parsa East and Kete Basan (PEKB), in what was once a ‘No Go’ area for coal mining in the state. Opening another mine in the core forest area could have deleterious consequences for the people living in it, the forest and the river Hasdeo.

The Hasdeo Arand region, spread across 1,70,000 hectares, is one of the largest intact dense forest area in Central India. Spanning across northern Korba and Sarguja districts in Chhattisgarh, the ecologically-sensitive area lies along the Gondwana belt.

- About Gond Adivasi community:

- Gond people have lived in parts of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh for centuries. Previously known to be hunter-gatherers, a significant number of Gond people have now turned to farming.

- In Hasdeo, a majority of the village population comprise adivasi communities, with Gonds being in large numbers. Their livelihood includes farming, gathering forest produce, collection and sale of non-timber forest produce, and agricultural labour.

- The villages affected by Parsa East Kete Besan and Parsa coal mines fall under the 5th schedule of the Indian Constitution

Coal sourced from PEKB, currently one of two operational mines, has been linked to the Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam (RRVUNL) since 2011 for thermal power projects in Rajasthan. RRVUNL gave the contract for mine developer and operator to Adani Enterprises. Parsa, the latest to get clearance, is contiguous to PEKB and Tara coal blocks. All three lie in the Hasdeo Arand coalfields. But the forest is a lot more than just fossil fuel reserves.

Elders from villages in Sarguja and Korba reminisce of their younger days as the glory days of the forest. Much has changed, they say. Bhagirati Sinh*, 62, who has lived in Khirti village for over 40 years, says, “We make chutney from the amla (gooseberry) we get from the forest. Earlier, in season, a tree bore fruit in abundance. We would use it for everything — it was as good as salt! And we’d sell it too. We also sold tendu (East Indian ebony), mahua and char (chironji, an almond-flavoured seed). But they’ve all reduced in quantity. Now, three of us pluck 400 tendu leaves with difficulty. Whereas before, one person used to pluck 400 by themselves.”

Sundar Ram*, a 55-year-old resident of Madanpur village, echoes similar views. “My grandparents and father told me there were so many trees in Madanpur that herds of elephants used to roam the area. They’ve mostly disappeared now — if the jungle goes, where will the elephants stay? Our situation is somewhat similar. We’re forest dwellers; if the jungle eventually disappears, where will we stay?”

When PEKB was granted stage II forest clearance in 2012, one of the conditions stated that “the state government shall not put forth any new proposals to open the main Hasdeo Arand any further for mining purposes.” However, 841 hectares of forest land will be diverted for the new Parsa coal block.

The change in Hasdeo over the decades can be attributed to various factors, natural and manmade. But coal mining (existing and upcoming) in a fragile ecosystem only exacerbates the threats.

Octogenarian Laxminath*, of Paturiadand village, describes how karma tyohar, the Gond harvest festival, has changed with the depleting forest. “We used to celebrate karma with a gusto back in the day. The men would dance in one line, and the women opposite them. A group would play instruments made from animal skin and sing. If a man wanted to get into the women’s line and dance with them, he would have to wear a costume — a skirt made from peacock and other feathers — on his waist. But there are hardly any peacocks left now. Anyway, everyone wants to dance to DJs now…”

Such conversations bring into focus the Gond community’s intrinsic relationship with the forest. Laxminath’s son-in-law works in the PEKB coal mine.

With mines taking over agricultural and forest lands, employment opportunities have reduced. Aside from unemployment, the adivasis have nowhere to live. While mine operators like PEKB say they have built houses for them, people like Josephine*, a local community volunteer with Hasdeo Arand Bachao Sangharsh Samiti and a resident of Morga village, have more to add. “It (PEKB) built some houses for the people, but if you see the houses you will not want to live there. They are like concrete cages. For someone used to living in open spaces, it is ridiculous to expect them to be happy in that colony. Most of the people who were allocated those homes left for other districts and villages.”

Stretches of land that served as elephant corridors and kept man-animal conflict at bay for decades were also disturbed when mining commenced in PEKB. There was a notable increase in the number of ‘attacks’ that occurred in villages closest to the mine, say Shivnath* and Parvati*. Their new house is less than 500 mts from the coal mine; originally, it used to be where the mine currently stands. “Two elephants attacked our village one week ago. If there was electricity, we could’ve seen them before they broke into our house. Before the mine, the elephants used to walk through the jungle. Now, there are no trees, where will they walk?” And without electricity, the tubewell doesn’t work. “We were given a generator, but diesel is too expensive. We used to cultivate rice earlier. Now we make baskets and mats out of bamboo. Two of our sons work in the mine. They (PEKB) gave the job because they took our land. But what’s the point?” ask the couple.

The mines are also impacting the quality of water. Alok Shukla, of Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan, says, “The Hasdeo river is extremely polluted. Waste from coal mines is let into the same river from which they source the water, and that affects everyone and everything dependant on the river. Chhattisgarh has a steadily increasing number of privatised rivers, and industrial projects are affecting them.”

The Hasdeo river system is the primary water source for irrigation and domestic use for thousands of locals. Sailhi naala, located between Hariharapur and Parsa villages, flows with moderate amount of water in peak summer. It flows to river Atem, a tributary of Hasdeo, and from the mining lease area. It used to be a perennial water source, but the natural flow has been affected. It has been diverted for PEKB’s expansion.

When the ‘No Go’ status for PEKB was revoked against Forest Advisory Committee’s (FAC) recommendations, it was pointed out that the total number of trees to be felled for this was 95,458, and that PEKB was an area sensitive to erosion. It is imperative to note that the FAC recommendation was overridden, paving way for the opening of new blocks like Parsa and Hasdeo Arand’s slow but steady demise.

There are 995 families that will be affected by the new coal mine. Out of that, 584 will lose agricultural land, and 411 will lose their homes as well as land. These families hail from six villages — Sailhi, Ghatbarra, Hariharpur, Fatehpur, Janardanpur and Tara.