- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

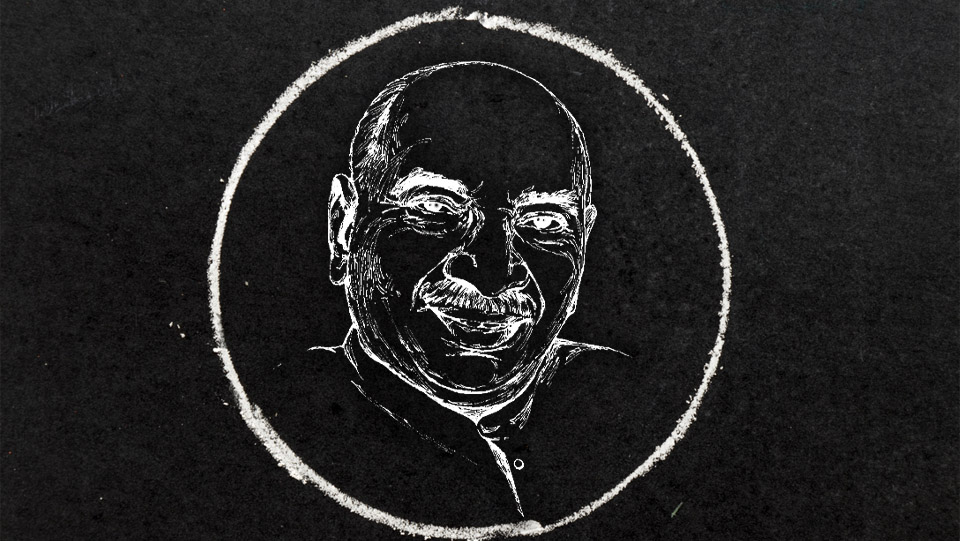

Remembering K Kamaraj: The man who shaped the dreams of Tamil Nadu

One evening more than five decades ago, K Kamaraj — the third chief minister of Tamil Nadu — was touring the countryside. As was his habit, he got down from his car and walked up to a group of agricultural labourers in a paddy field. He noticed a few children working alongside the group of men and women. When he asked why were the children not in school, a few women answered — for a bowl...

One evening more than five decades ago, K Kamaraj — the third chief minister of Tamil Nadu — was touring the countryside. As was his habit, he got down from his car and walked up to a group of agricultural labourers in a paddy field.

He noticed a few children working alongside the group of men and women. When he asked why were the children not in school, a few women answered — for a bowl of gruel that all those who worked in the fields got from the farm owners. That was why the parents brought their children along instead of sending them to school.

After Kamaraj returned to the state secretariat in Chennai, he called a meeting with senior officers and asked them to work out a scheme where students would get free lunch at their schools. When the draft proposal was tabled before the cabinet, a couple of ministers and officers wondered why the state should bear such ‘unproductive’ expenditure.

To this, Kamaraj pointed out that this was the only way to increase the literacy rate, prevent dropouts and create a pool of scientists, engineers and technocrats. They would lay the foundation for a vibrant economy, transforming not just their villages but the entire country, he believed.

The scheme was rolled out and was lapped up by poor parents who started sending their wards to schools across villages. A government order was also issued to enable reservation for scheduled castes and tribes, and the backward classes in schools.

The Mid-Day Meal scheme introduced by Kamaraj for school students in Tamil Nadu was later emulated and expanded by AIADMK and DMK governments in Tamil Nadu, the TDP government in Andhra Pradesh, and by various Congress and BJP governments across the country.

Kamaraj didn’t stop with that. He would ask village elders, businessmen, industrialists and traders if there was a school in their village. If not, he would ask them to open one. He tried to ensure there was a high school within a radius of 10 km anywhere in the state. Slowly but surely, the network of government colleges — arts, medical and engineering — was expanded.

Kamaraj, who was born on July 15, 1903, had dropped out of school after Class 6 because of poverty. But when he became the chief minister, he wanted to ensure that the next generation didn’t have to meet the same fate.

Today, there are a number of IAS officers, vice-chancellors, scientists, engineers, teachers, doctors and other professionals who admit they would never have made the grade had the Congress leader not devised an educational policy to make literacy a priority.

Marching on growth path

While his education policy had the right mix to promote scientific temper and social justice, the industry policy sowed the seeds of self-reliance and job-oriented growth.

Dams were built to provide irrigation facilities to backward and parched districts. Industrial estates were set up to encourage the manufacturing sector. Areas like Ambattur, Coimbatore and Hosur emerged as industrial hubs. While the Integral Coach Factory at Perambur, Neyveli Lignite Corporation and BHEL at Trichy were some of the important public sector organisations that were set up, power plants and low-cost housing projects too came up. Reservoirs were built to store water and healthcare was stepped up to fight polio and smallpox. All this wasn’t easy as the government had very limited resources, especially since the British raj had milked Madras of its riches.

While governments of today — endowed with budgets of several lakh crores — struggle to make progress, Kamaraj’s government had an annual budget of less than ₹1,000 crore for both infrastructure and development. His ministries — he served as the chief minister for nine years — were small in size with not more than eight ministers. Yet they proved to be more efficient than present-day cabinet of 30-plus ministers.

A big reason behind Kamaraj’s success was a corruption-free government. For instance, once a leader of a trade delegation from an East European country was in the state to secure a contract for setting up 10 sugar mills. When he offered a ‘commission’ of 10 per cent, Kamaraj, who was taken aback, first sought details about the total cost of the project. He then told the delegation that there was no need to pay a bribe. Instead, they could set up one more sugar mill for the original project cost.

Yet, Kamaraj — who had participated in the freedom movement and was imprisoned during the British Raj — gave up the lure of office in 1963 to rebuild the Congress party under what came to be known as the Kamaraj Plan. Amid growing public restiveness against the Jawaharlal Nehru-led Congress government following India’s disastrous war with China in 1962, Kamaraj — who was into his third term as CM of Madras — offered to step down. He also called for voluntary resignations of all senior Congress leaders holding ministerial office to work for the Congress party at the grassroots level. He then went on to become the Congress president.

As the party president, he picked two Prime Ministers, Lal Bahadur Shastri after Nehru died, and later Indira Gandhi, but fell out with the latter and left the Congress after the split in 1969.

However, he patched up with her in the 1970s and his Congress (O) in Tamil Nadu and Puducherry aligned with the Indira Congress. After his death, most party leaders and workers in the Congress (O) merged with the Indira Congress, a process which Kamaraj had initiated a few months before his death on October 2, 1975.

The Gandhian

Political observers of the time believe it was more than a coincidence that Kamaraj died on Gandhi Jayanti. Like the Mahatma, Kamaraj was known for his austere lifestyle. He would send just ₹15 every month to his mother and ask her not to seek any privileges as the mother of the CM.

If an industrialist or a businessman offered to make a donation to his party, Kamaraj would not even discuss or touch it. He would rather ask them to meet the Congress Treasurer K SG Haja Shareef if they wanted to contribute to the party, without any strings attached. At his home in Chennai, he would never offer visitors a cup of coffee or offer lunch. He knew that he could not afford it. If he began to do that, his salary would not be enough. Even the towels and shawls that were presented to him on his tours would be handed over to Bala Mandir school and other NGOs looking after orphans.

If there was any small change (coins or notes) left him every time he returned from a tour, he would give it to his friends, which included a couple of newspaper editors. They saved the money and informed him after a few years that a few thousand rupees had been saved and asked him to buy some land on arterial Mount Road that had come up for sale. Instead, he asked them to give the money to the Congress party which formed a trust and built the Kamaraj Thidal and the party office building called Satyamurthy Bhavan, named after his mentor Satyamurthy.

For Kamaraj, simplicity was a natural thing and not something to be worn on one’s sleeve. His government did not believe in cheap publicity even while launching big schemes, unlike today’s governments that splurge taxpapers’ money on advertisements.

When he died, the then DMK chief minister M Karunanidhi deputed two senior ministers to his residence to make arrangements for the funeral. One of them, K Rajaram, was moved to tears after he saw what Kamaraj had left behind in the house — a ₹100 note, three-four khadi shirts and a few dhotis.