- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

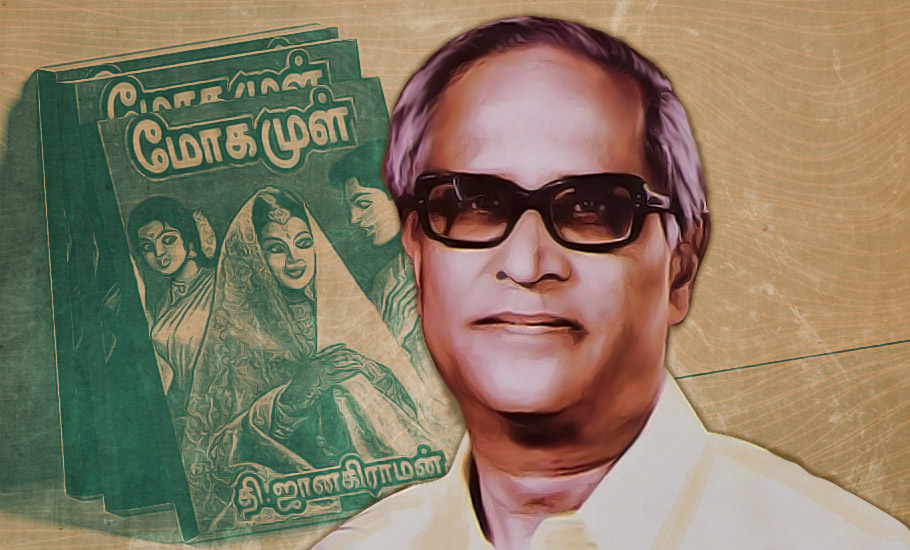

How a 1950s Tamil novel challenged the caste and age barriers to love

There aren’t too many couples who dare to defy the older-woman-younger-man relationship stereotype or to break the ‘great Indian caste barrier’. So to do both in the 1950s was not just unimaginable but a freaky rebellious step. Writer T Janakiraman decided to explore this subject in his novel ‘Mogamul’ (Thorn of Desire). The plot follows a 20-year-old man’s relationship with a...

There aren’t too many couples who dare to defy the older-woman-younger-man relationship stereotype or to break the ‘great Indian caste barrier’. So to do both in the 1950s was not just unimaginable but a freaky rebellious step.

Writer T Janakiraman decided to explore this subject in his novel ‘Mogamul’ (Thorn of Desire). The plot follows a 20-year-old man’s relationship with a woman 10 years older and from another caste.

The story takes place in Thanjavur where Cauvery river irrigated large swathes of agricultural lands. Even though the landlords practiced polygamy, they would still choose the other woman from the same community.

But one such landlord named Subramania Iyer breaks that norm and marries a woman from the Maratha community and they have a daughter named Yamuna. Due to her parents’ inter-caste marriage, Yamuna doesn’t find any suitor till she turns 30.

At a time when girls were pushed into marriage as early as 10, a woman remaining unmarried even after 30 was considered to be a big misfortune.

Yamuna and her mother live in another village in Kumbakonam away from the father, as was the norm those days. (Second wives weren’t allowed to reside in the same house or the village because of possible disputes with the first wife and her family).

At Kumbakonam, they are helped by another family and depend on a young man named Babu for most needs.

Although Babu and Yamuna doted on one another much like siblings, an unexpected sexual encounter with a married woman, makes Babu realise his hidden love for Yamuna.

But when Babu asks Yamuna to marry him, she turns him down, citing the difference in age.

A dejected Babu loses interest in everything. He fails to become the successful musician that his friends and family expect of him. Yamuna becomes his only object of obsession.

Finally, after seeing him suffer, Yamuna agrees to marry Babu. The novel ends on a positive note with Babu’s father Vaithi, despite being from a conservative family, approving the marriage unlike other men.

Adapting to film

The novel went on to inspire many other writers to broach similar subjects.

But not many filmmakers of the time dared to take up the challenge. Not even the likes of K Balachander and Balu Mahendra who are known for films defying social norms. It was a young IAS officer Gnana Rajasekaran who took the step and brought ‘Mogamul’ to the silver screens. His efforts bore fruits and he even went on to win a National Award for best debut director.

Rajasekaran, who was working as the district collector of Thrissur in Kerala in the 1980s, was a voracious reader and a film connoisseur. After Mogamul, he went on to make more path-breaking films such as Bharathi and Periyar.

Talking to The Federal, he recalls that he was initially not sure if the Tamil audience would accept such a subject. Unlike Malayalam and Bengali films, which were closer to reality, the Tamil film industry was still moving ‘slowly’.

“Finally, I decided to adapt ‘Mogamul’ since the story was not foreign to the Tamil audience and had its cinematic elements,” says Rajasekaran.

Another challenge he faced was in financing the film. But he managed to find a producer whose name was TN Janakiraman of the production company JR Circuit.

“He had gotten the rights of the novel to make it into a film and was searching for a suitable director. Hearing that, I approached him. It took two years to complete the film due to lack of money,” Rajasekaran says.

Although they released it only in Devibala theatre in Chennai, the director claims it ran for 100 days. But the film reached a wider audience through its repeated telecast on Sun TV, he adds.

Rajasekaran says his biggest challenge was to do justice to the novel.

“All along the making of the film, I was careful enough that the audience should not find the story obscene. It was like walking on a tightrope. At the same time, the essence of the story should not get diluted. While the story [in the novel] continues even after Yamuna accepting Babu’s proposal and goes on to talk about the man’s musical journey, I ended the film with Yamuna’s acceptance. I had doubts whether those who read the novel would accept this ending. I felt relieved when the family of Janakiraman appreciated the film,” he says.

The screenplay of the film has been recently published as a book by Kavya Publications, Chennai.

The man behind a cultural churn

In the Tamil cultural space, Mogamul, the novel and the film, is still considered to be early path-breaker that questioned conventional thinking and notions around love and other cultural norms of the time. And so it received a lot of brickbats both when it appeared as a series in a magazine and later published as a book in 1964.

‘Mogamul’ was charged with obscenity. However, it started getting attention gradually and Yamuna became a ‘dream girl’ for many. This rarely happens in the world of Tamil literature.

On T Janakiraman birth centenary (officially celebrated on February 28), Thanjavur is celebrating the writer and his pioneering work.

Having done his education in Thanjavur and Master’s degree in literature, Janakiraman, fondly referred to as ‘Thi Jaa’, took up teaching for some time. From 1954, he worked in All India Radio, Chennai, for 14 years. He was then transferred to New Delhi in 1968 and worked there till his retirement in 1979. He then served as an honorary editor of ‘Kanaiyaazhi’, a literary magazine.

Janakiraman had started penning stories from the age of 17. During his college days, his introduction to fellow writers from Thanjavur like MV Venkatram, Karichaan Kunju, made him take up writing on a serious note, as a profession itself.

Writer Ku Pa Rajagopalan acted as a guide to him in traversing the modern Tamil literature. This enabled him to publish his first novel ‘Amirtham’ at the age of 24. He wrote 10 novels, two novellas, three travelogues and many short stories.

His stories mostly revolved around transcending cultural norms, especially with regard to sex. Being a Brahmin and writing such stories drew him massive outrage from his community, which treated him as an outcast.

Even though his most noted work ‘Mogamul’ is considered a magnum opus, he was awarded the Sahitya Akademi award in 1979 for his collection of short stories ‘Sakthi Vaithiyam’. He died in 1982 at the age of 61.

“The works of Janakiraman are cultural and literary documents of Thanjavur,” says his contemporary and writer Venkatram. Janakiraman, he adds, constantly recorded the landscape of the district in his stories, and did it accurately.

Interestingly, Venkatram appears as a character (with the same name) in the novel ‘Mogamul’.

But despite walking the uncharted path, Janakiraman somewhat struggled to show the same emotions in his real life when it came to his daughter’s marriage.

A regular, doting father

Just like his cult novel, Janakiraman had to face a similar dilemma in his real life. His daughter Uma Shankari, while doing her academic research, met well-known social worker Gorrepati Narendranath, who was from another community in Andhra Pradesh, and they got married.

The couple is known to have led many struggles for the welfare of farmers from their residence in a village near Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh.

“Appa, like any other parent, was worried,” says Shankari. “When my father came to know about our love affair, he was worried about the reactions from our relatives. Although I tried explaining to him, he was not convinced. He went to Hyderabad to meet the parents of Narendranath and they discussed the matter.”

She goes on to say that although he was satisfied after meeting them, Janakiraman still hesitated to take the matter forward. “He advised me against it a lot but I was steadfast. Seeing my determination, he finally gave up.”

She adds that as a parent she too faced the same kind of dilemma when her children decided to marry outside caste.

Shankari says she was not aware of the responses the novel got and how Janakiraman responded to it.

“I was only a year old then. So, I don’t know about how the novel was received. As far as film is concerned, we can say that the film has embraced the story of ‘Mogamul’ instead of saying it has adapted the novel.”