- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Coronavirus sparks xenophobia against Chinese, Northeast Indians

Du Fengyan, 35, a Chinese from Beijing arrived in Mumbai, India on January 29, a day before India reported its first coronavirus case in Kerala. The airport authorities had screened him for the virus and had cleared him. As Fengyan toured the maximum city for a week, staying out of a hostel, little did he know what was in store for him, as the number of coronavirus cases rose slowly in...

Du Fengyan, 35, a Chinese from Beijing arrived in Mumbai, India on January 29, a day before India reported its first coronavirus case in Kerala. The airport authorities had screened him for the virus and had cleared him.

As Fengyan toured the maximum city for a week, staying out of a hostel, little did he know what was in store for him, as the number of coronavirus cases rose slowly in the country.

The first instance of shock was when the hostel staff told him that he couldn’t stay there any longer. When asked why, they just told him because he was a Chinese.

Since Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic originated in Wuhan in China, several nationals of the country across the world have faced discrimination and became victims of xenophobic attitude by citizens of various countries including India.

“I was healthy and had no symptoms of the virus. Despite that, the hostel had a problem and they cited other customers raising concerns over my stay,” Fengyan says. “I tried to confront and explain but they were unwilling to listen.”

As many hotels in the city limits rejected him, Fengyan moved to Navi Mumbai hoping to get some accommodation. There too, he had to shift three hotels in five days, he says. With the help of a friend, he managed to go to Goa and where he faced little resistance.

A few days later in early March, he made a bike trip to Mumbai along the coast. By then, the number of coronavirus cases was on the rise globally, crossing 100,000 by March 7. When he returned to Goa again, almost everyone was aware of the pandemic and that it had a China connect. The problem got worse for him.

“People started to call me ‘coronavirus’. They didn’t realise the mistake or perhaps didn’t understand that it was racial slur against me. Only when I called it wrong and warned them, they stopped,” Fengyan says.

On March 16, he moved from Goa to Karnataka. When he was screened at the state border and was allowed to travel, Fengyan thought the problem was over. But at Udupi, a budget hotel which initially accepted him, later asked him to checkout after they realised he was a Chinese.

“When I refused, they called the police and I had to confront. Their (police’s) attitude was no different. When I stood my ground, they accepted to get me tested for COVID-19,” Fengyan adds.

At midnight, the doctors at a nearby district hospital cleared him of having no coronavirus symptoms, post which the hotel accepted him back. The next day, faced with similar problems, he slept in a makeshift tent near a temple in Kottigehara enroute to Chikamagaluru. The subsequent day, he put up his tent at a gas station, not having any other choice.

He realised that his fellow nationals living in various parts of the country were facing similar problems. For Fengyan, who had the experience of living in tents as a traveller in India and South Africa before, this was not painful. But the racial slur against him and his countrymen in the wake of coronavirus pandemic, put him off.

In Singapore, thousands of residents signed a petition asking the government to ban Chinese nationals from entering the country. In Japan, #ChinesedontCometoJapan was trending last month.

With the US President Donald Trump repeatedly terming the novel coronavirus as “China Virus”, xenophobia has only increased. From New York City to Los Angeles, people of Asian descent have been reporting xenophobic incidents on social media over the past month.

Northeast Indians too targeted

That the Northeast Indians are often referred to as Chinese in slang in various parts of the country is not new. But with the coronavirus pandemic causing unprecedented fears, they are now often being targeted for the same.

Students and working professionals, living in cities like Chennai, Bangalore, Chandigarh and Meerut faced similar problems. A wave of bigotry has engulfed some Indians who think people from Northeast, who share facial features like the Chinese.

On March 3, two students from the north-eastern states were attacked by men on motorbikes who threw water balloons at them and called them “coronavirus” near Delhi University’s North campus. Much to their dismay, the police officer tried to normalise the situation without helping them. Similar incidents were reported in other parts of the country.

Recently, four students living in a Punjab village called Chunni Kalan who faced similar attacks, took to Facebook to post a video explaining the racial attack and appealing to people to wake up at least now and realise the mistake. As a fallout, the students were asked to vacate the hostels and rented accommodation in various places.

On Friday last (March 20), the Northeast India Welfare Association in Chennai filed a complaint with the Commissioner of Police AK Vishwanth alleging racial discrimination in the city in the wake of rising cases of coronavirus.

From Darjeeling in north Bengal, the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration chief Anit Thapa urged the West Bengal government to take strict action against those discriminating people from Darjeeling and north-eastern states. He cited several instances where people from hills were harassed for their Mongoloid features, dubbing them carriers of coronavirus.

Taking note of such cases, Union Minister Kiren Rijiju said on March 18 said strict advisory would be issued to all States and took the matter with the North East division in the Ministry of Home Affairs.

“Some incidents of racial remarks against Northeast people have emerged in some parts of India in the wake of #Coronavirus due to cultural ignorance, prejudice mindset & lack of understanding, Matter discussed with NE Division, MHA. Strict advisory is being issued to the States,” Rijiju who represent Arunachal Pradesh, one of the North Eastern states, tweeted.

Am shocked to read this. Delhi Police must find the culprit and take strict action. We need to be united as a nation, especially in our fight against Covid-19 https://t.co/roMOMq2jNf

— Arvind Kejriwal (@ArvindKejriwal) March 23, 2020

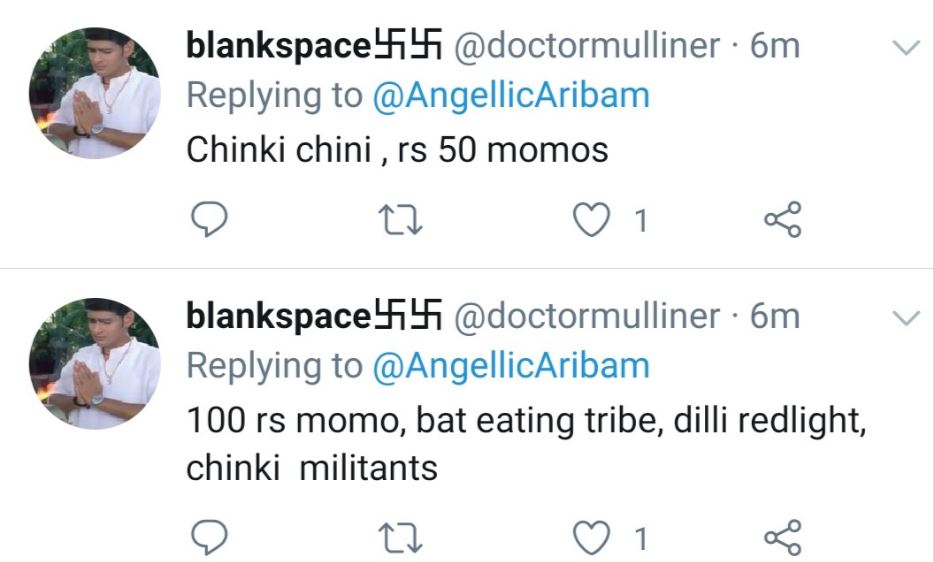

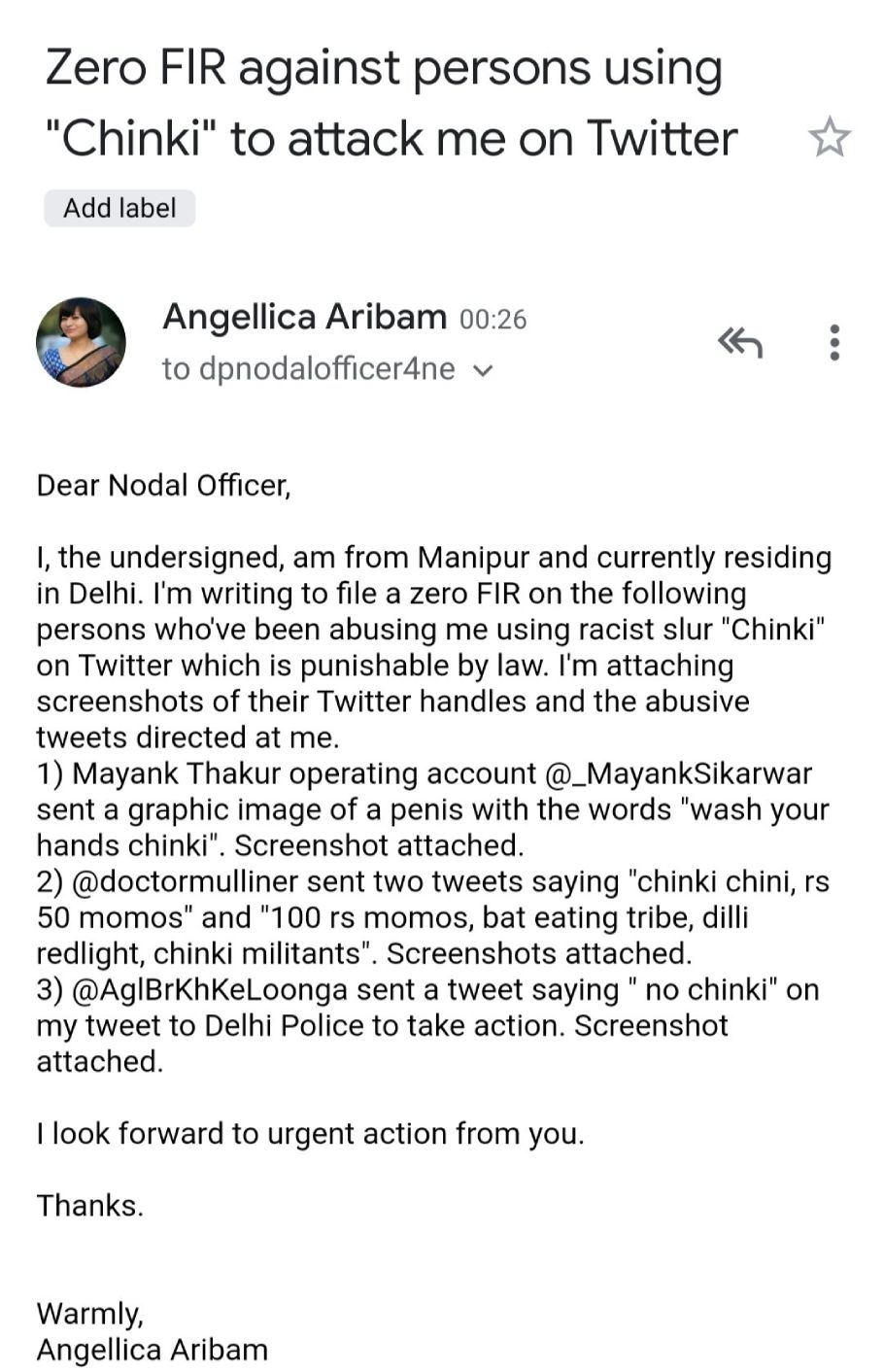

The bigotry and discrimination not only was it visible on the streets, but also on social media where several students were being targeted. Former Delhi University student leader, Angellica Aribam had filed a police case in response to racist comments directed at her on Twitter, with one user calling “bat eating tribe”.

Such discrimination and bigotry existed even before. Be it the North East Exodus in 2012 or after the murder of Nido Tania, son of an Arunachal Pradesh MLA in 2014 in New Delhi, the political class have not woken up to create awareness among the masses and implement the rules to punish the offenders. After five years of long battle, the court in 2019 convicted four people and sentenced them with rigorous imprisonment.

In 2014, the Ministry of Home Affairs set up a committee under the chairmanship of MP Bezbaruah, a retired IAS officer, to look into the concerns of the Northeast people living in other parts of the country.

The committee recommended measures to set up special police initiatives for safety and security of the Northeast people living in Delhi, NCR and other parts of the country while also suggesting to take measures to educate other people about the Northeast.

“While the Delhi Police assured me of action and said they would take it up with Twitter, I wish the respective governments implemented the Bezbaruah committee recommendations,” Aribam said.

Aribam, who has been living in Delhi for the past 16 years, says she took up political activism of such discrimination and racial prejudice.

“The political class wake up during such incidents and make soothing statements. But after that they forget,” she says, calling out political leaders including Rijiju.

“There is no space for us to engage and create awareness among the people, except on college campuses in parts of the country. That should change and it would not come without the political will of the current politicians,” Aribam says.