- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

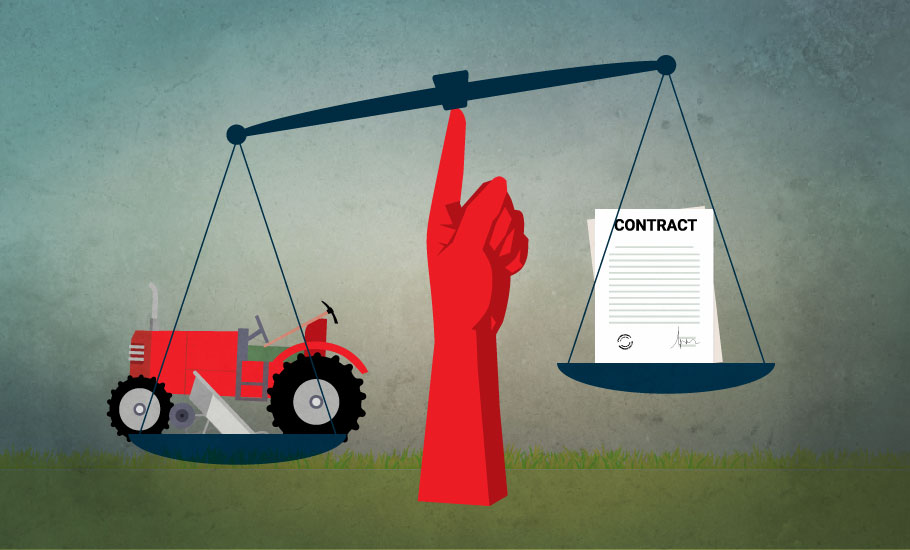

Contract farming needs more than an ordinance

While from the outside, contract farming may seem a success story where the farmers were better off compared to their peers, there were issues.

Unlike other farmers in Ranebennur, north Karnataka, 29-year-old Chamanna R Goudra was a busy man in February 2019. When other farmers did not cultivate anything after harvesting the rabi crops, Goudra dug two borewells in the drought prone area. He did multiple-cropping and cultivated tomato, splash and watermelon in his father’s 2.6 acres of farmland. He even engaged 13 farm labourers...

Unlike other farmers in Ranebennur, north Karnataka, 29-year-old Chamanna R Goudra was a busy man in February 2019. When other farmers did not cultivate anything after harvesting the rabi crops, Goudra dug two borewells in the drought prone area. He did multiple-cropping and cultivated tomato, splash and watermelon in his father’s 2.6 acres of farmland. He even engaged 13 farm labourers and paid them on time.

He could do all this because he earned about ₹8-10 lakh per season as compared to the average ₹2-3 lakh earned by others. And for this he had to thank multinational seed companies which had set up base in Ranebennur.

HM Clause, Bayer Crop Sciences and Vegetable seeds, Syngenta, Mayhco had engaged with select farmers for seed cultivation through contract farming. They appointed social programme officers and area production managers to coordinate with the farmers. Their staff acted as liaison officers and agents between the farmers and the company.

Goudra says they supplied hybrid variety seeds and gave farming advice like how to cross-pollinate, how to monitor crop size, pest controls and the growth of the plant.

Issues over flawed contracts

While from the outside, it may seem a success story where the farmers were better off compared to their peers, there were issues.

The farmers were made to enter into contracts which were drafted by the companies to suit their interests. And for the farmers it worked on trust and the actual contract copy is never given to them.

“We sign the agreement with the company and are not given a copy of it,” Goudra said in 2019.

The companies expect germination and genetic purity of 96-98% and would make the payment only three months after harvesting. But if the crop doesn’t match the expected quality, they do not buy the seeds and, as per the contract, the farmers are forbidden from selling the seeds to the market or competitors. Left with no choice, farmers are often forced to sell the crop to the companies at a price fixed by them, which is much lower than the initial agreed one.

Also, there was no clause for compensation if the crops were affected by drought or floods, leaving the farmers at the mercy of the company. Farmers and farm labourers are not told about the redressal mechanism too.

Not a rosy affair

Gherkin cultivation in India had a boom in 2000-2012. Being an export-oriented crop, companies entered into contract farming with farmers giving a good price. But when the export market collapsed for gherkins after Russia moved to countries like Vietnam, the farmers were left high and dry suddenly. Similar is the case with rose farming in and around Bangalore. Rose export companies moved from one farm to another once the land was exploited to the full extent.

67-year-old DM Ventakappa in Hosakote village near Bangalore shifted from vegetable cultivation to rose farming as companies elicited interest and assured a higher price. He did so for five years. Once his land was subjected to over-exploitation and faced a water crisis, the company moved to another farmer in 2016.

Recently, a juice company had orally agreed to buy guava from a farmer for ₹2.5 lakh. Once the produce was ready to be harvested, the COVID-19 lockdown came into force. The company shut its unit and refused to buy the produce. The farmer lost the entire money. The company showed no remorse as there was no ‘force majeure’ clause to take into effect the unforeseen circumstances and natural calamities.

Contract farming extends to non-crop activities like poultry farming, for both eggs and broilers, and are undertaken by large enterprises in south Indian states. Even food processing industries like juice manufacturing companies enter into contract for fruit crops. The companies usually went through agents or tied up with big farmers as it was tedious to make individual contracts with each farmer with small lands.

What studies say

The issues of flawed contracts are well documented. A report by French documentary filmmaker Linda Bendali in 2017 stirred a debate on the exploitation tactics of seed companies, including HM Clause.

Another report ‘Soiled Seeds’ by Dr Davuluri Venkateswarlu, director, Glocal Research, Hyderabad, highlighted child labour and labour exploitation by such companies in 2015.

While the Centre’s Agriculture Produce (Marketing and Development) Regulation Act, 2003, promoted contract farming and nearly 20 states provided contract farming provisions in their respective APMC laws, and some even passed separate Contract Farming Acts, violations and exploitations continue unabated.

A 2014 study by a Panjab University research scholar on the PepsiCo plant in Channo in Sangrur district of Punjab noted that while farmers benefited and led to a rise in area under cultivation under contract farming, the biased nature of the firms against smallholders had a negative effect.

“These biased contracts create social problems in the society. These types of contracts also create social differentiation and unrest. The capacity of small scale farmers to participate in the commercial market is much different than large scale farmers,” it said.

Known to sue farmers time and again, the MNC last year took 11 farmers in Gujarat to court for growing a variety of potatoes specially used in Lays chips, claiming “rights infringement”. The company demanded ₹1.5 crore from each farmer. It withdrew the case later and went for an out-of-court settlement.

New ordinance a game-changer?

The Centre in June passed “The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020” to give a legal binding for such farm practices. The new law allows farmers to contract with companies or farm aggregators.

Agriculture Minister Narendra Singh Tomar said crop diversification cannot happen without an assured market and that the ordinance will encourage farmers to engage with buyers like processors and large retailers. “Farmers can now enter into a contract agreement with buyers to sell the produce at pre-determined rates before the sowing,” he said.

While the new legislation is aimed at benefitting farmers and encouraging smaller traders to source produce directly from farmers, the logistics and cold-storage aspects still remain a concern.

The Act stipulates that the agreement shall specify the purchasing prices, the method used to arrive at the fixed price, the quality, grade and standards, and inspection procedures.

However, the legislation does not mandate any minimum compensation clause in case of drought, flood or unforeseen circumstances. It leaves these to the concerned parties. And for redressal, a sub-divisional authority is appointed to resolve disputes.

Interestingly, the Centre has diluted the powers of the state in such cases. In a controversial provision, the legislation states that contracts entered under the Act shall be exempt from the application of any state laws on the sale and purchase of such farming produce. Also, it bars parties from suing the state or Centre, the sub-divisional and appellate authorities for doing anything that is in “good faith”.

‘Mandis will still dominate’

Ajay Vir Jakhar, chairman of Punjab State Farmers’ and Farm Workers’ Welfare Commission who leads Bharat Krishak Samar, opines that the ordinance on contract farming may not benefit a large section of farmers as the mandi system would still prevail in the wake of farmers largely holding small land parcels and that the aggregators will still lead the game with companies trying to evade responsibilities.

“The ordinance provides for aggregators to enter into a contract with farmers. So ideally, the companies will route through them and they all will be influenced politically or by the market,” Jakhar says.

He says the legal cost will outweigh the direct purchase cost and hence, the companies would still want to avoid entering into a direct contract with farmers.

“It’s not going to be a game changer. The ordinance may not affect, whether good or bad, a large section of farmers. The companies will still evade the process as it’s too tedious to get into contract with small farmers,” he adds. “Neither will the farmer have time and money to fight legal battles.”

Emails sent to HM Clause’s regional head and India general manager asking whether the company would henceforth engage with farmers directly and gave them a contract copy, did not elicit any response.

“If our existing laws are strictly enforced, farmers can benefit out of it. But the government does not ensure effective implementation of certain legislations,” Davuluri of Glocal Research says.

On the other hand, he says, companies are not interested in educating farmers on contractual terms and redressal systems. “The contracts are drafted to suit the corporate interests.”