- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Black magic and Bengalis: The wicked narrative against women

It was early morning and a road trip from Delhi to Shimla looked inviting enough to make Arumita Mitra slip into a dreamy nap inside the car. Outside, the sun was shining bright and the trees were swaying gently. Arumita was not alone in the car. A young couple, Arumita’s close acquaintances, and their 10-month-old baby were also travelling along with her. Not long into the journey, Arumita...

It was early morning and a road trip from Delhi to Shimla looked inviting enough to make Arumita Mitra slip into a dreamy nap inside the car. Outside, the sun was shining bright and the trees were swaying gently. Arumita was not alone in the car. A young couple, Arumita’s close acquaintances, and their 10-month-old baby were also travelling along with her. Not long into the journey, Arumita was jolted awake by the cries of the baby. Even as the parents tried their best to comfort him, the cries continued.

While it’s natural for babies to cry, his father somehow was convinced it was Arumita’s presence that had something to do with it. “Bangalan kala jadu karti hain (The Bengali woman did some black magic)” was how he later described the whole episode.

“The father felt it was not natural. I later got to know from common friends that he alleged it was because I did some black magic,” says Arumita, a research assistant at the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO).

But this wasn’t the first time Arumita was faced such an outrageous allegation because of her linguistic/regional/cultural identity.

“When I came to Delhi first, I was shocked by the culture of sexist cuss words thrown around by men and normalised by everyone else around them. When a male friend rectified his behaviour after I pointed it out to him, all that his friends, including women, had to say was — Bangalan ne vash mei kar liya hai (the Bengali women has cast a spell on him).”

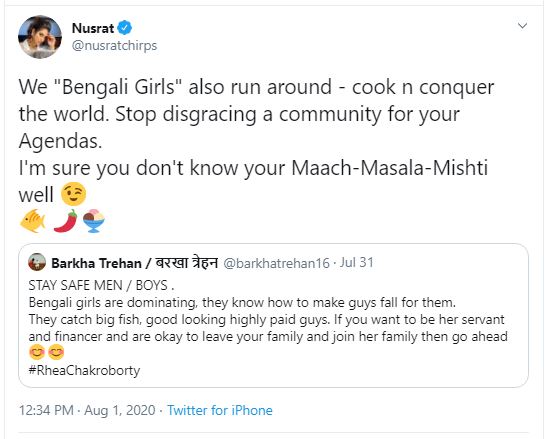

While Arumita and many more Bengali women continue to face such bias, the recent vilification of actor Rhea Chakraborty, the girlfriend of late actor Sushant Singh Rajput, suddenly opened the floodgates of hate against the entire community, particularly its women.

The hate campaign started with Sushant’s father filing an FIR against Rhea charging her with abetment to suicide, misappropriating his funds, and distancing him from his family. And then the late actor’s sister reportedly accused Rhea of casting a spell on him. It didn’t take the roaring news channels and ugly social media feeds to amplify the attack and target all Bengali women.

While many more Bengali women continue to face such bias, this is not without precedent.

Deep-rooted misogyny and racial bias

Branding women as daayin (witch) is common across states but how Bengali women landed in the vortex of all this is something even rationalists are scratching their brains over.

What goes behind the stereotyping of the Bengali woman as the long-haired, red-lipped, irresistibly bold enchantress who turns everyone into puppets of her will?

Guwahati-based academic Gopa Majumdar has an answer. “Men often tend to listen to someone they respect and consider to be better than them. Bengali women perhaps have that effect on men and everyone else because of their hard-earned achievements compared to their counterparts in the rest of the country.”

But it is, she adds, the hyper-sexualised image of Bengali women created in popular culture — literature and cinema, especially Bollywood — that has also added to the narrative. “After all, Indians are famous for equating the inexplicable with the paranormal. So the same goes for natural charm.”

Majumdar strongly believes that the Manjulikas (Bhool Bhulaiyaa) and Bulbbuls (Bulbbul, Netflix), even if unwittingly, have also contributed in perpetuating this to a certain extent.

But rationalist Prabir Ghosh is still at his wit’s end over the “magical spell of Bengali women”.

“Incidents of torturing women by labelling them as witch were rampant in Purulia district of West Bengal. Even five years ago, such incidents were quite common. But now it’s no longer the case,” says Ghosh, president, Rationalist Association of India. Stating that there’s no such thing as black magic, he throws a challenge to anyone who can prove its existence to the organisation.

Wicked link

Another reason behind this, many feel, could be the ‘Bengali babas’ — self-proclaimed healers known for selling what they call ‘medication’ for gastrological problems, ‘Bengali baba ka churan’ (digestive powders). Some of them claim they know black magic. Interestingly, most of them are not even Bengalis. Often, they are dressed in black, appearing like tantrics and forge a Bengali identity to sell their churans.

In 2018, one such Bengali baba was apprehended by the police from Mumbai’s Nallasopara suburb. The posters of the suspect, identified as Riyaz Chauhan, were found in local trains carrying various names. Many identified him as Bengali baba. According to an official, he used to claim that he knew black magic and charge ₹3,500 from commuters, convincing them that he would ward off their problems using special prayers.

Tantric practices of the earlier days had been associated with black magic. In popular belief, such practices were held at Shakti Peethas, major pilgrimage sites. Shaktism is one of the major sects of Hinduism in Bengal and Assam, and tantra has been one of its subtraditions.

But neither tantric practices nor misogyny is limited to Bengal.

Utsarjana Mutsuddi, former researcher, School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University, says this entire trope of “Bengali women can do black magic to keep men under their spell’ is psychologically violent towards women.

“Bengal and Bihar are teeming with cases where women are being branded as witches who practice black magic. Such ostracisation usually has very terrible aftereffects. From the woman being lynched to her succumbing to neglect. This is a reality that lurks behind the very casual but fatal sexism,” she says.

That such sexism translates into everyday bias is hardly a surprise. For instance, Arunima Chatterjee, an aviation professional, was denied a house on rent in Jaipur after the landlord came to know of her Bengali roots.

“In 2016, I was looking for a house. When I met the landlord, his wife asked me about my native whereabouts,” Arunima recalls.

The moment Arunima mentioned Kolkata, the landlady said they don’t rent out their house to Bengalis, and “certainly not to the Bengali women”.

She quotes the lady, “You people practice black magic. There are two young men in the house. God saved us in time. Just leave.”

What could have further added to this notion of widespread practice of witchcraft in Bengal is the famous Wiccan priestess, Ipsita Roy Chakraverti, who has her roots in Kolkata. In 1986, she declared herself a witch, prompting strong protests led by the Left government led by Jyoti Basu.

In an interview with Firstpost a few years ago, she pointed out how perceptions of witchcraft – once considered a powerful positive force – were twisted into something dark and malicious.

Earlier, in 1982, the Left government was also accused of burning to death 17 monks and nuns of the Ananda Marga, a spiritual organisation that propagated tantric practices, in broad daylight in Kolkata’s Ballygunge area. The same group was again accused in an arms drop case in 1995 in Purulia district of the state. “It goes without saying that the buzz created by these incidents only added to the narrative that black magic is widely practised in Bengal,” says Majumdar.

But the fact that rumours and half-baked investigations into such incidents would one day be taken to such an extent that a very modern India will target the women from one community is what astounds most in Bengal.

Perhaps what Chakraverti said many years ago is true even in this age of reason: “Every strong woman is a witch.”