- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

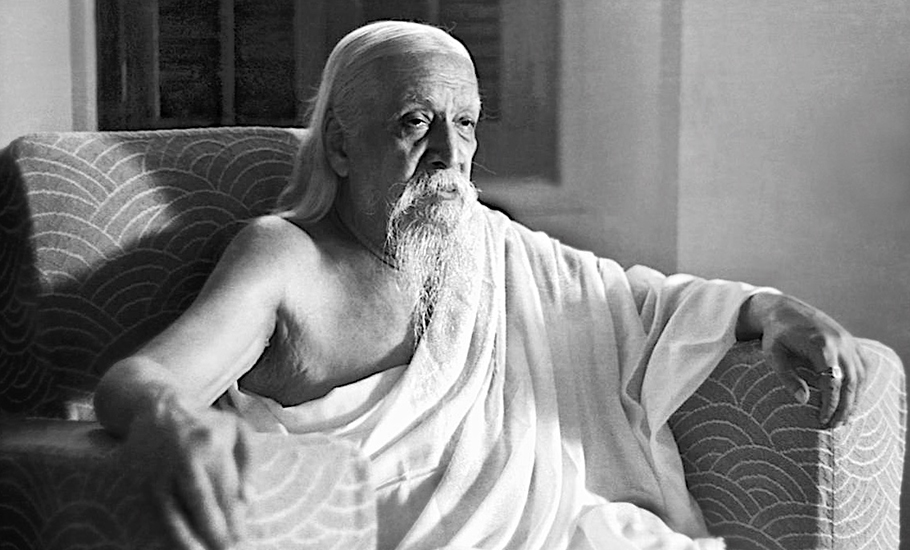

Aurobindo Ghosh: The revolutionary who turned spiritualist

“I had no urge toward spirituality in me, I developed spirituality. I was incapable of understanding metaphysics, so I developed into a philosopher,” wrote Aurobindo Ghosh of himself in 1935. Aurobindo Ghosh, who came to be known later by his honorific title Sri Aurobindo, attained iconic stature in the first two decades of the 20th century, metamorphosing into a spiritual leader from being...

“I had no urge toward spirituality in me, I developed spirituality. I was incapable of understanding metaphysics, so I developed into a philosopher,” wrote Aurobindo Ghosh of himself in 1935.

Aurobindo Ghosh, who came to be known later by his honorific title Sri Aurobindo, attained iconic stature in the first two decades of the 20th century, metamorphosing into a spiritual leader from being a militant Bengal anti-British revolutionary.

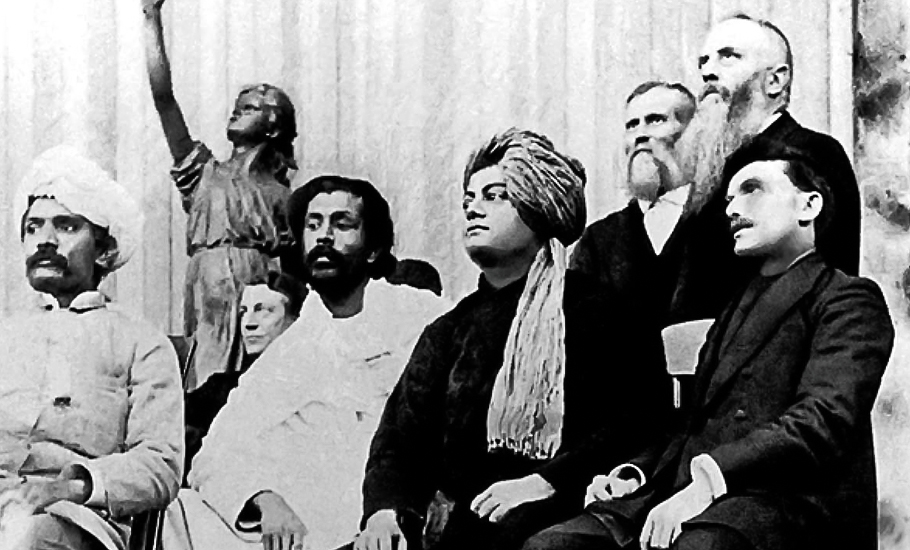

Even in spiritualism, he stood apart. Unlike the more conventional religious guru Ramakrishna Paramahamsa or a broader political-cultural historic personality like Rabindranath Tagore, Aurobindo Ghosh came to symbolise modern spirituality embedded in Indianness. In this, he was second only to Vivekananda. He was a prominent figure among the small band of Indian revivalists from Bengal at the turn of the last century. Though these revivalists drew heavily upon Hindu tradition, they were not exactly Hindu religious revivalists. Rather, they represented a more secular and broader Indian socio-cultural renaissance against the colonial hegemony. Aurobindo was one among the early intellectual trailblazers of Indian awakening against the British rule. No wonder, his legacy continues to inspire many today.

As the country observes the 150th birth anniversary of Sri Aurobindo, a look back into his story reveals two Aurobindos and not just one. One was the militant political activist Aurobindo until 1910. And post 1910 emerged the spiritual thought-leader Sri Aurobindo. This difficult-to-believe transition was a historical fact and this makes the Aurobindo story even more intriguing and fascinating.

Aurobindo before 1910

By a strange coincidence, Aurobindo Ghosh was born on 15 August. The year was 1872. Incidentally, by another coincidence, 1872 also marked the beginning of Hindu revivalism in Bengal as documented by historian Amiya P Sen in his book Hindu Revivalism in Bengal: 1872-1905—Some Essays in Interpretation.

1872 was the year of the first Bengal Census which triggered a sense of communal identity among Bengali Hindus after it showed a high 48 per cent Muslim population in the province and the subsequent censuses revealed a relatively higher growth of Muslim population in some key regions of Bengal.

1872 was also the year when the Brahmo Marriage Act was passed which stipulated the minimum age for marriage as 14. It allowed inter-caste marriages provided the contracting parties declared that they were not Hindus. Prominent Brahmo Samaj reformist Keshub Chandra Sen took the lead in getting this law passed. The Hindu orthodoxy vehemently opposed this law. Amiya P Sen has documented in his book the powerful Hindu backlash against this law which marked the beginning of the “Hindu awakening”. However, the reformists’ lobby suffered a setback when Keshab Chandra Sen himself married off his daughter at the age of 13 in 1878 and the Brahmo Samaj split. Another reformer, Rabindranath Tagore also married a 10-year-old girl. The conservative Hindus rejoiced at these.

In such a surcharged backdrop, Aurobindo was born in an affluent Bengali bhadralok family in Calcutta, which had its origins among the enlightened landed nobility in Hooghly district. Bengali bhadraloks those days were harbingers of a hybrid colonial modernity. A hybrid one in the sense of being an eclectic combination of Victorian mannerisms in looks and speech and the conservative Bengali ethos. This contradiction between Westernization and Indianness defined Aurobindo’s evolution in the future.

At the turn of the 20th century, most Bengali bhadralok families sent their sons—and seldom their daughters—to England to study. Aurobindo’s father was a civil surgeon, who had studied in Edinburgh, and he sent his three sons to get educated in England and put them under the care of an orthodox Christian priest. Aurobindo studied in St. Paul’s School and then in King’s College. He detested the conservative Christian milieu where he stayed and studied and longed to return to Indianness.

While the other two brothers could not qualify for the ICS, Aurobindo cleared the qualifying open competitive exams and could well have made it to the ICS. But the rebel in him came out as he detested a future civil service career too. He deliberately absented himself from a riding session at the fag end and hence he was disqualified.

By coincidence, the Maharaja of Baroda was in London at that time and Aurobindo’s fathers’ friends arranged for a slot for Aurobindo in Baroda Civil Service and he returned to Baroda in 1893. Aurobindo spent the next 13 years in Baroda Civil Service. He got his first exposure to worldly affairs in the revenue department but, not comfortable with that, he quickly shifted to teaching in a Baroda college.

Aurobindo frequently visited Calcutta, ostensibly to visit his brothers and other family members but actually to interact with anti-British activists and revolutionaries who were gathering in Anushilan Samiti there, a sub-rosa outfit. Aurobindo plunged himself into hectic anti-British political activity from 1902 to 1910, shifting from Baroda to Calcutta in 1906. He joined a radical faction in the Congress, became a prominent leader, and attacked the moderate leaders including Tilak. He became the editor of Bande Mataram, a radical nationalist daily. He presided over the Indian National Congress conference in Surat in 1907 when the Congress itself formally split into the moderate and radical wings.

Aurobindo was arrested in May 1908 under sedition charges in the Alipore Conspiracy Case. As the sedition charges could not be proved in court, he was released in May 1909. He started an English paper Karmayogin and a Bengali weekly Dharma. The British Police launched several new prosecutions against him and his Karmayogin and anticipating arrest again he escaped to the French colonial enclave of Pondicherry (now Puducherry). However, quite inexplicably, there he abandoned all his political activities. He even declined repeated offers to take over as president of the Congress. The year 1910 thus marked a spiritual turn in his life and the rest of his life he devoted to spiritualism.

Aurobindo after 1910

In Pondicherry, Aurobindo started an ashram, which later came to be known as Aurobindo Ashram, ostensibly for yoga training. He also started publishing a philosophical-theological monthly Arya in which he wrote a series of essays on Gita and Isha Upanishad. The main work defining his spiritual views Life Divine, the Synthesis of Yoga was also first serialized in Arya before appearing as a book. He continued to publish Arya till 1921. Aurobindo became a prolific writer and his collected works published later added up to 36 volumes. Though started with a handful of his followers, the Ashram soon expanded into a larger community, a spiritual community to be precise.

Spiritual pursuit with a difference

“…I had no eye for painting — I developed it by Yoga. I transformed my nature from what it was to what it was not. I did it in a special manner, not by a miracle and I did it to show what could be done and how it could be done. I didn’t do it out of any personal necessity of my own or by a miracle without any process. I say that if it is not so, then my Yoga is useless and my life was a mistake — a mere absurd freak of Nature without meaning or consequence. You all seem to think it a great compliment to me to say that what I have done has no meaning for anybody except myself — it is the most damaging criticism of my work that could be made. I also did not do it by myself, if you mean by myself the Aurobindo that was. He did it with the help of Krishna and the Divine Shakti. I had help from human sources also,” he wrote explaining his spiritual pursuit in 1935.

Though the firebrand militant nationalist Aurobindo remained politically conscious even after his religious-spiritual turn in Pondicherry, his activity did not evolve into an armed religious anti-colonial resistance. Nor did it blossom into a religio-political cult of Hinduism—neither as a Hindu variant of latter-day moderate Islamists nor as some kind of new age avatar of the old Hindu Mahasabha. Though Aurobindo was familiar with the tricks of the trade of armed militancy and had acquired adequate expertise through his involvement with outfits like the Anushilan Samiti and others, he rather shunned active politics. However, Aurobindo did not become totally apolitical. He continued to comment on political developments in his journals. He even sent an emissary to argue with Congress leaders that they should accept the Cripps Mission’s proposals for a dominion status.

The British colonial government did not believe in Aurobindo’s spiritual turn. They thought it was only a ruse. Considering Aurobindo as the “most dangerous man in India,” they kept Aurobindo under surveillance for long even after his retreat into spiritual life in Pondicherry. But Aurobindo’s renunciation of active politics altogether and taking entirely to spirituality still remains a puzzle. His autobiographic notes and other writings do not throw adequate light on this mysterious transition.

Aurobindo’s spirituality was rooted in Hinduism, especially in the Vedanta heritage of Vivekananda, no doubt. But the Aurobindo Ashram he established in Pondicherry was not a replica of Hindu monastic orders established by the run-of-the-mill Hindu Swamis and mutt leaders. Nor did it evolve into a commercialized sect similar to that of later-day godmen. It was something special and different.

Mirra Alfassa, a Jewish French spiritualist, and her husband Paul Richard, came to Aurobindo’s ashram in Pondicherry for the first time in 1914. Mirra became an ardent spiritual collaborator of Aurobindo. After returning to France, she came back again to Pondicherry and stayed there forever. Later, she was called Mira and the Mother.

Aurobindo and the Mother developed Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry as a community based on communitarian sharing like Shantiniketan developed by Rabindranath Tagore but with a key difference.

While Shantiniketan developed by Tagore was largely a creative cultural community based on literary and artistic activities like music, theatre and dance, Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry evolved into a spiritual community while Auroville, established as its adjunct, sought to come up as a New Age international socio-cultural knowledge community.

Spiritualism versus political activism

Is spiritualist endeavor really incompatible with radical politics, especially of the anti-colonial genre? What led Aurobindo to renounce politics? Can there be a spiritualist brand of anti-colonialism? Aurobindo and Mirra Alfassa had some other contemporary models. Annie Besant, who had developed the Besant Theosophical Society, which too was an ashram of sorts, took active part in Congress politics and even became its president in 1917. Margaret Elizabeth Noble, the spiritual companion of Vivekananda, who rechristened her as Sister Nivedita, took an active part in the activities of the Anushilan Samiti, and to avoid any fallout of her radical political association on Ramakrishna Mission, she had to formally dissociate herself from that despite continuing its spiritual moorings.

Leela Gandhi, the postcolonial theorist from Brown University, in her book Affective Communities—Anti-Colonial Thought and the Politics of Friendship lists some critiques of spiritualist anti-colonialists. As per her summary, author Parama Roy of California University discredited the anti-colonial efforts of Sister Nivedita (1867–1911) on the grounds that her nostalgic spiritualism appealed exclusively to recessive strains within Indian nationalism, favouring orthodoxy and revivalism over nationalism and reformism.

Leela Gandhi also points to philosopher Ashis Nandy discerning a contaminating authoritarianism in the spiritual style exercised by the Mother in Aurobindo Ashram, which reinforced rather than mitigate the colonial hierarchies. Leela Gandhi quotes Ashis Nandy: “The Ashram itself became, under her powerful presence…highly status conscious, politically conservative and a means of oppressing the people around. After Aurobindo’s death, for a while it even opposed decolonisation of Pondicherry.”

Starting with anarchistic egalitarianism of renouncing material possession, the wheel had come full circle when the Ashram management fought with the management of Auroville over property and forced the latter to separate from it. There was also a heavy dose of petty politics and infighting surrounding the Ashram. But to the credit of Aurobindo Ashram, it must be conceded that they never descended to the level of wrongdoings of Asaram Bapu’s ashram or Puttaparthy ashram.

Both Shantiniketan and Aurobindo Ashram today are pale shadows of what was originally visualised by their architects. A trend seen with all institutions which take after historic personalities or ideologies. The organised Church, supposed to disseminate the teachings of Jesus Christ, launched crusades and backed colonialism—and its genocides—to the hilt. Parties, and even entire states like USSR and China, which claimed to adhere to the philosophy of a great humanist and libertarian like Karl Marx, perpetrated pure horror against humanity and freedom. But despite its share of problems, Aurobindo Ashram so far has not fallen so low.

Chennai-based social scientist R Vidyasagar told The Federal: “India is a land of eternal paradoxes. One such irony of history is a character like Amit Shah visiting Pondicherry last month [in late April 2022] and praising Aurobindo as if he belonged to his own parivar. A month earlier RSS boss Mohan Bhagwat was also heaping praise on ‘Saint’ Aurobindo. The saffron leaders were trying their best to appropriate Aurobindo’s legacy despite the fact that the religiosity and spirituality of Aurobindo was not even remotely connected to their saffron brand of Hindutva. But then, these are the people who are trying to appropriate even Gandhiji and Tagore to subserve their current hegemony. But it is bound to fail for obvious reasons.”

…a place where the needs of the spirit and the care for progress would get precedence over the satisfaction of desires and passions, the seeking for pleasures and material enjoyments. — The Mother

Aurobindo Ashram too failed to distance itself from such Saffron endeavors. More importantly, it has miserably failed to update its own spirituality, to make it appealing enough to 21st century new generations. Short of that, it will keep vegetating. But it has ample strong points as well for a recrudescence of a new spirituality suited to this post-humanist age.

(This is the first of a two-part series on Sri Aurobindo and his legacy. Read the second part here.)