Tamil Nadu honour killing: What took judiciary so long to deliver justice

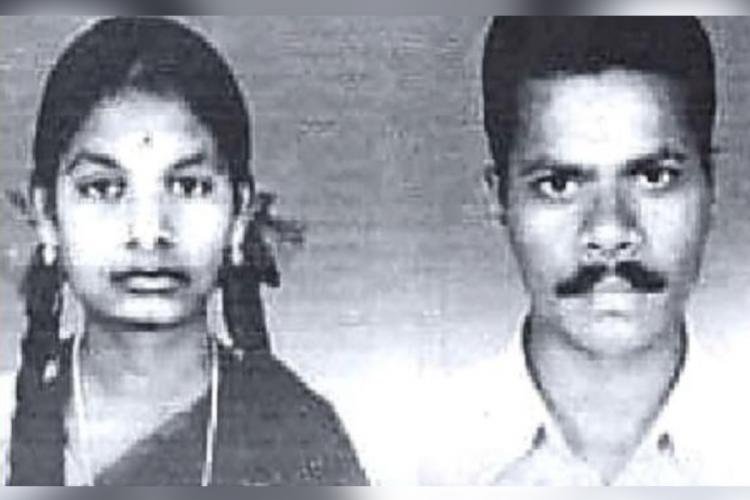

Tamil Nadu’s S Murugesan and D Kannagi finally got justice, 18 years late. On Friday, a Cuddalore district special court handed capital punishment to one person and life imprisonment to 12 others for killing the couple in 2003.

Behind the verdict is a story of delays and procedural lapses and transfer of judges, that indicts the judiciary for working at a snail’s pace in clearing cases filed under the SC/ST Act.

For the inter-caste couple was apparently killed for “honour”. Dalit youth Murugesan, 25, and Vanniyar girl D Kannagi, 22, both hailing from Kuppanatham, a village in Cuddalore, had eloped on May 5, 2003, and got married. They had met at Annamalai University and fallen in love.

After the wedding, Murugesan sent Kannagi to his relative’s house in Moongilthuraippattu, a village in then Villupuram district and now in Kallakurichi, and himself stayed at another relative’s house in Cuddalore, to escape the eyes of the girl’s relatives.

But on July 8 that year, the girl’s relatives found the couple and brought them to Kuppanatham in the early hours, where they were administered poison and their bodies burnt separately.

“The gruesome murder came to light six days later through the Tamil magazine Nakkheeran and only then the police filed a case,” said advocate P Rathinam, who fought the case for 18 long years.

The incident became Tamil Nadu’s first “hate killing”, in which mostly upper-caste people kill not only the lower-caste/Dalit boy or girl, but also their own child in the name of honour.

The case has many other firsts – it has become the first case in which a special court hearing SC/ST cases has pronounced a capital punishment for the main perpetrator. It is also the first case in which police officials have been sentenced to life under the SC/ST Act, and it is the first case in which a suspended but in-service police official has been given a life sentence.

The court awarded the death sentence to Kannagi’s brother Maruthupandi and gave the life term to the rest, including her father, a police inspector who was then sub-inspector and a retired DSP who served as inspector then, for alleged mishandling of the case.

‘Corruption and neglect delayed the case’

The information shared by advocate Rathinam, exclusively with The Federal, shows that at each step of the case, the police, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and the judiciary turned a blind eye to many facts that delayed the delivery of justice.

“First, the police filed cases against the parents and relatives on both sides, stating that they poisoned their own children. That caused the first of the delays in the case,” said Rathinam, who is known for his activism on Dalit issues and also fought the 1997 Melavalavu massacre case and provided much needed support from the backend in the 1993 Athiyur Vijaya case.

“Three days after arrests were made, my friend and I went to Murugesan’s house and got the details. Following that, we worked to get Murugesan’s relatives bailed out. That took some time,” he added.

After that, a case was filed in the Madras High Court, where it got stuck in the usual procedural delays and was transferred to the CBI in 2009.

“Unfortunately, the police at first did not file a case under the SC/ST Act. So the accused sought preventive detention bail. The CBI itself brought the case under the SC/ST Act and that took some time. Adding insult to injury, the then CBI officials took money from the accused and named two relatives of Murugesan (Iyyasamy and Gunasekar) falsely in the chargesheet. We filed a writ petition against that and struggled to get their names removed from the case. This caused further delay,” the advocate explained.

Under the SC/ST Act, there is a provision that gives the right to victims to appoint advocates of their choice to represent them. It can be done with the help of the district collector.

“The CBI appointed a junior lawyer for the case. We moved through the district collector who cancelled the appointment and prayed to the high court to appoint an advocate of our choice. This further delayed the case,” Rathinam revealed.

He further pointed out that during the investigation, officials recorded the deposition of the witness in English. “But it should be done in Tamil. So, it took some time to record the version in Tamil and translate into English. This took more than a year or so,” he added.

In between, two judges were transferred in the trial court and some amendments were brought into the Act in 2016. All of this further delayed proceedings in the murder case.

Yet another major lapse by the CBI, Rathinam noted, was to not add Murugesan’s aunt, who was there at the spot when the murder happened, as witness.

The advocate also rued the apathy towards the case by Dalit political parties and a judge who happened to be a Dalit himself. “The leader of a Dalit political outfit had even advised Murugesan’s father not to fight the case, since it would deepen fissures between Dalits and Vanniyars,” he said.

When asked about whether he came under attack or was ever threatened by the upper castes in all the years that he fought the case, Rathinam said no. “When I had fought the Melavalavu panchayat president murder case, I was threatened by the upper castes. But not this time,” he said.

‘Need more special courts’

A week before the court order, Madurai-based Evidence, an organisation working for Dalit rights, came out with an RTI reply that revealed shocking data.

It showed that 300 Dalits were murdered in Tamil Nadu between 2016 and 2020, and only in 13 cases were sentences pronounced.

The reason why such cases are piling up is because the state has no sufficient judicial mechanism, alleged R Murugappan, state coordinator, Social Awareness Society for Youths, Villupuram.

“According to the SC/ST Act, each district court should have a special court to hear cases filed under this Act. But of the 38 districts in Tamil Nadu, there are special courts in only 14 districts – Trichy, Thanjavur, Madurai, Tirunelveli, Villupuram, Sivagangai, Dindigul, Ramanathapuram, Virudhunagar, Pudukkottai, Cuddalore, Namakkal, Theni and Tiruvannamalai,” he added.

In the special courts that do exist, there are no full-time judges. Judges from other courts look after these cases once a week. They usually don’t conduct the trial, but just adjourn it, lamented Murugappan.

Though it is often argued that the SC/ST Act has teeth, activists like Kathir, founder of Evidence, demand that a special law must be enacted to curb hate killings.

“In hate killing cases, not only is the lower-caste boy or girl killed, but sometimes the boy or girl from the upper caste is also murdered. In some cases, the upper castes leave the Dalit boy or girl untouched but murder their own children. These kinds of murders happening within castes are not seen as ‘honour killing’ and thus not recorded under the SC/ST Act. So a special law is needed,” he explained.

Also read: Jaipur parents feel no remorse in honour killing of Keralite son-in-law