Death threat prompts West Bengal MLA to get his statues made

TMC legislator Jayanta Naskar recently spent hours sitting passively as a model before a sculptor he commissioned to chisel his two life-sized statues. Naskar fears he could be killed anytime by his political adversaries, and hence the need to make arrangements to ensure he does not slip into oblivion after death.

Trinamool Congress (TMC) legislator Jayanta Naskar recently spent hours sitting passively as a model before a sculptor he commissioned to chisel his two life-sized statues.

The two-time MLA from Gosaba fears he could be killed anytime by his political adversaries, and hence the need to make arrangements to ensure he does not slip into oblivion after death.

The narcissistic desire of the septuagenarian MLA to immortalise himself might sound amusing, but the entire episode bears out a harsh reality of Bengal politics — it’s synonymous with violence. The state tops in political murder in the country, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB)’s latest report.

“What will happen after my death? This thought first came to my mind a year or so ago, after I got to know from special branch of the state police that my political opponents are conspiring to kill me,” Naskar told The Federal.

Police said they came to know about the threat perception after they intercepted telephonic conversation of an inmate of Alipore Central Jail. After the interception, Naskar’s security cover was updated to ‘Y’ category. Currently, he has 11 police guards deployed for his protection.

The police presence, however, did not assure him of his safety. “The day they will come to kill me, even police will not be able to protect me. I am a public figure and I’m constantly mingling with people. Anytime a bullet can come from within the crowd and snap my life,” he mused.

Naskar has reason to be worried. It was only in February last year, his party colleague and Krishnaganj MLA Satyajit Biswas was shot dead by unidentified assailants inside a Saraswati puja marquee near his home at Hanskhali in Nadia district.

Senior BJP leaders Mukul Roy and Ranaghat MP Jagannath Sarkar were among the five booked in connection with the murder. On Thursday (March 12), Roy was interrogated by sleuths of the Crime Investigation Department (CID) of the West Bengal police in connection with the killing of 39-year-old Biswas.

Related news: BJP not to give up on politics of polarisation in Bengal

Attack on political rivals is not rare in Bengal. Around 50 people were killed in political violence across the state in 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

A home ministry advisory sent to the state on June 15 last year had said political violence in state had claimed 96 lives and that the unabated violence over the years was a matter of deep concern.

The NCRB’s latest report said that with 12 murders, the state recorded the most number of political killings in the country in 2018. But even that figure is grossly conservative. At least 25 people, mostly BJP workers and supporters, were killed during the state’s rural elections that year.

Trendsetter CPI(M)

The CPI(M), which ruled West Bengal for over three decades, was a trendsetter in political killings.

The most horrific incident of post-independent political killing in the state took place at Sainbari in Bardhaman district on March 17, 1970, seven years before Left Front came to power.

On that day, CPI(M) workers bludgeon two brothers, known to be Congress loyalists, to death in front of their mother. The brutality did not end there. After killing the two, the assailants made their mother eat rice soaked in the blood of her two sons.

The accused in the heinous crime, Benoy Konar, Anil Bose and Nirupam Sen, all prominent leaders of the CPI(M), later went on to occupy ministerial positions in the state. This shows the impunity enjoys by the accused in cases related to political violence.

Since the 1970s, killing and violence has become effective political tool to stifle dissent and eliminate rivals.

Not always threats come from opponent parties. Factional feuds within the party too take an ugly turn sometimes.

Naskar did not directly name anyone as a suspect, but dropped enough hints to suggest that his prospective killers are from his own party. “Those who wanted to kill me were earlier with the CPI(M), but of late they have started circling around our party,” he said.

“I am getting threats now and then,” he claimed.

But what prompted him to get made two statues of himself?

“I wanted to ensure my statues are installed after my death so that people remembers me even after I am gone,” he said.

“If my family members or supporters had made statues after my death, they would have used my photographs. Statues made by seeing photographs are not as good as the ones sculpted using a real life model,” he said.

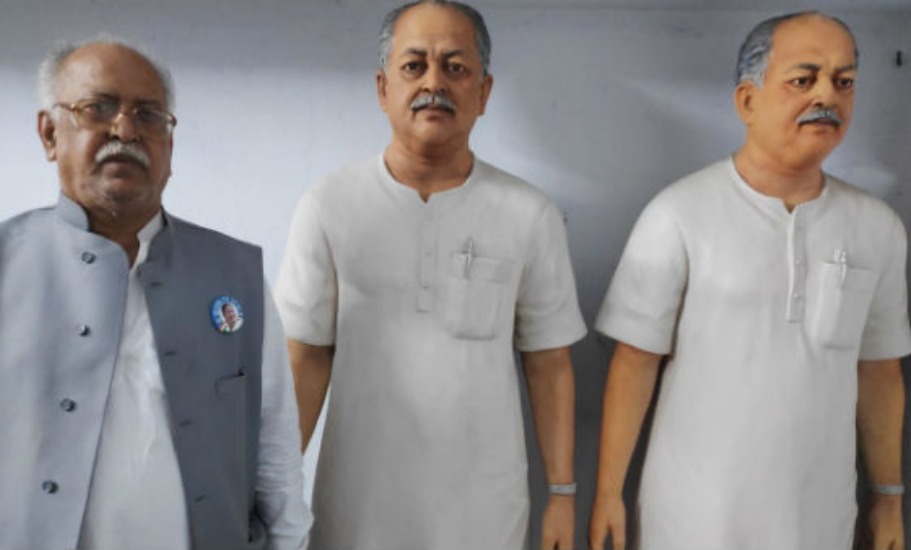

Hence, Naskar decided to sit before a sculptor in Kumartuli, the potters’ town in north Kolkata, for around two hours per sitting to get his two statues made. “I had to go there at least five to six times to have the two statues made,” he said with a sense of satisfaction.

For the two fibre statues, Naskar said he has spent around ₹1 lakh. The statues are now carefully kept in a room at the ground floor of his Bagulakhali home in Chunakhali in South 24 Parganas district, gathering dust and awaiting the death of their master.

Related news: Why people are willing to die for political cause in Bengal?