Who was Oppenheimer? Read about genius scientist, a bundle of contradictions

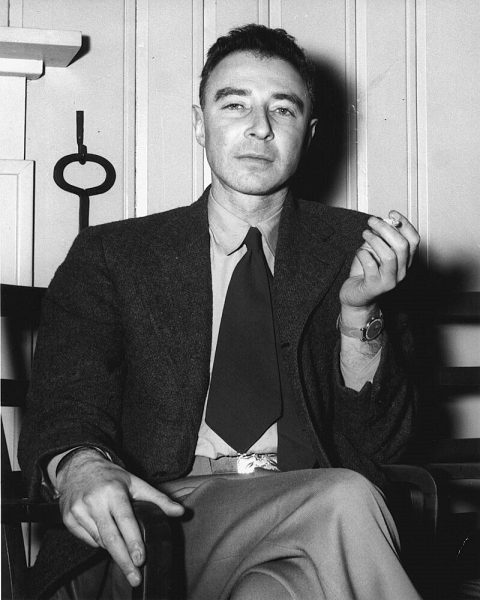

He was 20th century’s most compelling, charismatic and enigmatic public figures. The brilliant American theoretical physicist J Robert Oppenheimer, who was a celebrated genius in his field, however, was also viewed as a man full of contradictions.

This controversial scientist is in the news with acclaimed director Christopher Nolan’s biopic blockbuster all set to hit the screens on July 21. The role of Oppenheimer is being essayed by Cillian Murphy of ‘Peaky Blinders’ fame, and a giant cast supports him which includes the likes of Emily Blunt as wife Kitty Oppenheimer, Robert Downing Jr, Matt Damon and a host of other Hollywood stars.

Oppenheimer’s biographers say he harboured an ‘overweening ambition’ to successfully accomplish the awe-inspiring and terrifying task given to him by the US government to build the world’s first atom bomb during World War II and forever mark his place in scientific history. But, he also had conflicting feelings of guilt about his creation.

Oppenheimer openly agonised over the atom bomb after he and his team had built it at a military laboratory in a remote area in Los Alamos, New Mexico, terming it ‘evil’ and ‘devil’s work’ in interviews. He later described nuclear weapons as instruments of ‘aggression, of surprise and of terror’. And he said this even as he was acting as a nuclear weapons consultant for the US government in the late 40s.

After the deployment of the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which effectively ended World War II, Oppenheimer met President Harry Truman in October 1945. He famously told the US president, “I feel I have blood on my hands.” The President admonished him telling him the blood was on his (Truman’s) hands and to let him worry about that. Truman later told an aide: “I don’t want to see that cry baby scientist ever again.”

Another report says that one morning Oppenheimer was heard crying over the imminent fate of the Japanese calling them “Those poor little people, those poor little people.” In a meeting with his military counterparts, however, according to his biographers Bird and Sherwin, he was focussed on the right conditions for the bomb drop. “They must not drop it in rain or fog… Don’t let them detonate it too high… Don’t let it go up higher or the target won’t get as much damage,” he is supposed to have said.

His contradictions have left his biographers foxed.

Oppenheimer’s life history

Born to first generation German Jewish immigrants who had become wealthy through the textiles trade, he grew up in upscale New York city. From an early age, Oppenheimer demonstrated his intellectual prowess, reading philosophy in Greek and Latin. An obsession with minerals even led him to give a lecture at the New York Mineralogical Club when he was just 12 years.

He entered Harvard University when he was 18 and graduated in chemistry after just three years summa cum laude (with highest praise). Realising his true passion lay in physics, he then pursued graduate work at Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, under JJ Thomson, the Nobel laureate who discovered the electron.

In Cambridge, he seemed to have been grappling with mental issues and infamously deliberately left an apple, poisoned with laboratory chemicals, on his tutor’s desk. According to reports, he was described as being at that time a “fragile young man who had a near-nervous breakdown”. He was suspended from Cambridge and put on probation but the facts are unclear as the records have been destroyed.

Also read: You can’t experience Oppenheimer to the fullest in India | Christopher Nolan | Cillian Murphy | IMAX

However, at that time, he discovered literature and saved himself going under. All his life, he moved between poetry and science. According to his biographer Bird, he was deeply charismatic, and even attractive to women. He wasn’t a “nerdy personality”, but Bird says he loved French literature, British poets and Ernest Hemingway novels and got fascinated with Hindu mysticism and Bhagavad Gita.

Oppenheimer termed the Bhagavad Gita as “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.” He reportedly always kept his worn copy on his desk, and often gave copies to friends.

Early in 1926, he met the director of the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Göttingen in Germany, who recognising his talents invited him to study there. It would prove to be a turning point in his career as he became part of a community that was driving the development of theoretical physics. These people became his life-long friends and later joined him at Los Alamos for the Manhattan Project to develop the bomb.

By the time World War II broke out, Oppenheimer emerged as a respected professor at the University of California, Berkeley having made some significant contributions to science. Bird describes him as a sort of a caricature of the eccentric professor. He was “intellectual omnivore who read Sanskrit, loved Elizabethan poetry, rode horses and made a great martini”.

During his time at Berkeley, he fell in love with Jean Tatlock, a student at Stanford University School of Medicine and a Communist Party member, which later became an issue in his security clearance hearings.

Though Oppenheimer was possiblly “sympathetic to communist goals,” he never officially joined the party. The couple broke up in 1939 and, a year later, he married a biologist Katherine Puening with whom he had two children.

During their marriage, Oppenheimer cheated on his wife by reviving his affair with Tatlock. In 1944, Tatlock committed suicide.

Developing the bomb

In 1941, two months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D Roosevelt approved a programme to develop an atomic bomb triggered by a letter written by Albert Einstein that “breakthroughs in nuclear fission” can give way to extremely powerful bombs of a new type.

Oppenheimer’s so-called communist political leanings didn’t prevent him from being recruited, in early 1942.

For three years, Oppenheimer and a huge team of scientists worked towards the creation of an atomic bomb out of a military laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico. At 5.29 am on July 16, 1945, after almost three years of sustained work the first nuclear detonation in history unfolded. It was known as the Trinity test.

After the war ended, Oppenheimer was appointed chairman of the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) from 1947 to 1952. It was here he opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb.

Victim of a witch-hunt

In 1953, at the height of US anti-communist Mc Carthyism wave, Oppenheimer was accused of having communist sympathies, and his security clearance was taken away by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). This was done at a highly publicised security hearing.

The scientific community, with few exceptions, was shocked by the AEC decision. Much later, in 1963, President Lyndon B Johnson tried to redress this injustice by honouring Oppenheimer with the Atomic Energy Commission’s prestigious Enrico Fermi Award. However, it seems Oppenheimer never recovered from the public humiliation.

Oppenheimer’s tussle with duty

Oppenheimer seemingly looked to the Bhagawad Gita for comfort. For Oppenheimer the war (World War II) would continue whether he took part in it or not, as it had been for Arjuna in ‘Mahabharata’. There would be loss of life with or without him. He consoled himself as having done his duty to his country.

But, he is often quoted as saying after the bomb was tested: “I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and to impress him takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Through the last years of his life, Oppenheimer maintained pride at the technical achievement of the bomb and guilt at its effects. He even started to say that the bomb had “simply been inevitable”.

Oppenheimer spent the last 20 years of his life as director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, working alongside Einstein and other physicists. A chain smoker since adolescence, Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in 1967, at the age of 62.

And a New York Times obituary wrote: “This bafflingly complex man nonetheless never fully succeeded in dispelling doubts about his conduct.”