The Last Courtesan review: How a tawaif built a life for herself, and her son

‘Aurat ne janam diya mardon ko, mardon ne use bazaar diya. Jab ji chaha masla, kuchla, jab ji chaha dhutkar diya (The woman gave birth to men, and men gave her a marketplace. When they wished, they crushed her, and when they desired, they discarded her)’ is the first line of a nazm (poem) by Sahir Ludhianvi that perhaps provides a poignant introduction to the story of Rekhabai, a courtesan who illuminated the dark alleys of Calcutta and Bombay in the 1980s with her brave and resilient heart.

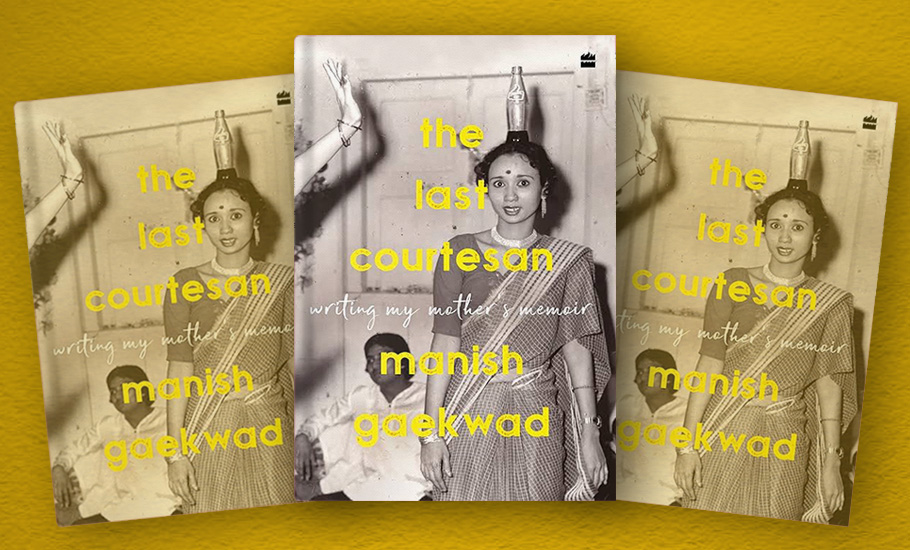

She transformed the bazaar to which she was sold and confined into a key that unlocked the doors to a life led by freedom and dignity — the very things she was denied, as a woman, and as a tawaif. The Last Courtesan: Writing My Mother’s Memoir, published by HarperCollins India, chronicles the life of this remarkable woman who narrates her tale of survival and success to her son, Manish Gaekwad. Manish, in turn, writes his mother’s memoir, a powerful story of agency and strength that shines through unfavourable circumstances.

The agency to be flawed

Popular culture, be it literature or cinema, has frequently appropriated, romanticized, glorified or done all three to the lives of courtesans. Take Meena Kumari’s Pakeezah, for instance; the film and heroine greatly admired by Rekhabai herself, who perhaps sees herself as the tragedienne like Kumari, Gaekwad writes. However, he refuses to paint his mother as the glamorously tragic character longing for love, like Pakeezah does for Sahibjaan, or Umrao Jaan does for Nawab Sultan, or Devdas does for Chandramukhi.

Also read: Courting Hindustan review: A glimpse into the lives of courtesans across ages

He also avoids portraying her as a radical agent of social change, as Bhansali does in Gangubai Kathiawadi. This brings me to my point: films and literary works, regardless of their artistic value, often tend to create a captivating but limiting image of tawaifs. This treatment deprives them of the right to shape their own lives without being reduced to either damsels or heroes. Why can’t they be depicted as humans, just like you and me?

With The Last Courtesan, Gaekwad shatters this monochromatic image and grants his mother the agency to be flawed, human, and still extraordinary, which she undoubtedly is. He traces her life through stumbles and mistakes, but what is truly extraordinary is not just that, but rather how she rises from those setbacks. She doesn’t wallow with her hair floating in a tub of rose-scented water (like a scene straight out of a Hindi film); instead, she weeps, screams, curses, and fights back. Even in her moments of helplessness, Rekhabai is not the tragic figure she believes herself to be in her later years. She is a spirited woman, seeking everything that society has told her she cannot have.

Not a victim of the world’s vices

She is a true enigma because, to be completely honest, very few people possess the courage to break free from their predicament and create a life of their dreams. Most individuals succumb to misery and grief, embracing them and learning to live with them. When life deceives them, hope is typically the first casualty. It is almost expected for a child who is sold and thrust into such circumstances to remain unaware of any other life, perpetuating a cycle of pain, indignity, and fear. However, Rekhabai, as mentioned before, defied expectations and became an enigma, as Gaekwad eloquently expresses.

His mother refused to be a victim of the world’s vices. She resolved to build a life for herself and, even more so, for her son. She could have easily allowed her surroundings, filled with men disguised as monsters, to shape her son’s destiny. Instead, she sought and fought to provide him with the life she had never experienced. Our understanding of what makes a good mother, father, or parent is burdened by archaic and rigid notions. We claim that two men in love cannot be capable parents, or that a single woman or a courtesan is unqualified to be a mother.

Also read: Truth/Untruth review: Mahasweta Devi’s exploration of love and lust in Calcutta of 1980s

Meanwhile, heterosexual individuals trapped in loveless marriages are deemed suitable for parenthood. Through Gaekwad’s account of his mother’s journey, we are compelled to reconsider these beliefs and realise that children should not be mere byproducts of sexual encounters. They deserve to be raised and nurtured with love and affection. Therefore, only those who possess the courage to raise good children selflessly and bravely should be considered eligible for parenthood.

Grace in the face of suffering

There is something significantly honest about The Last Courtesan that enchants you because in a world with air-brushed personalities and highly edited stories, Gaekwad’s rendition of his mother’s tale is politically incorrect here and dangerously courageous at other places, making it stand out. There is something beautiful about stories that have no purpose to serve, no ending, or beginning, stories that are lives and Rekhabai’s life is one that inspires greatly, even though it doesn’t try to, or perhaps that is why.

Also read: How Indian queens across history scripted stories of valour and victory

Gaekwad also delves into the intricate dynamics of power, love, and exploitation that existed within the courtesan-customer relationships, offering a nuanced perspective on the complexities of their existence. His prose is engaging and evocative, transporting readers to the opulent settings of courtesan houses and allowing them to experience the sights, sounds, and emotions of the time. The inclusion of historical anecdotes, personal accounts, and cultural references further enriches the narrative, providing a comprehensive understanding of the courtesan world and Rekhabai’s life.

If there’s one thing you are going to read this weekend, let it be Manish Gaekwad’s The Last Courtesan, a heartfelt account of a tawaif’s life that is filled with sorrow and pain, but nevertheless the story that becomes immortal is that of strength and grace, even in the face of extreme suffering and struggle.