CUET has its pluses, but keeping coaching institutes at bay is a challenge

The entrance test faces the danger of becoming yet another stress-inducing choke point for students which coaching institutes and factory-schools will thrive on

Hundred per cent. In recent years, that has been the ‘cut-off’ required in Class XII exams conducted by any board to enter some colleges in Delhi University (DU) for admission to popular subjects such as computer science, commerce and economics.

Now, boards across India that conduct Class XII exams vary in their quality of syllabi, strictness in evaluation as well as in the quality of teachers and learners. For instance, the topper of Bihar board’s Class XII exam in 2022 across academic streams, with a 96.4 per cent aggregate, would be rejected in many colleges affiliated to Delhi University. In contrast, a student from a private school in Lucknow affiliated to the CBSE board, who scored 100 per cent in all subjects, would find it easy to enter some famous colleges in Delhi. Also, in the absence of a normalisation process, the admission process was skewed in favour of lenient boards.

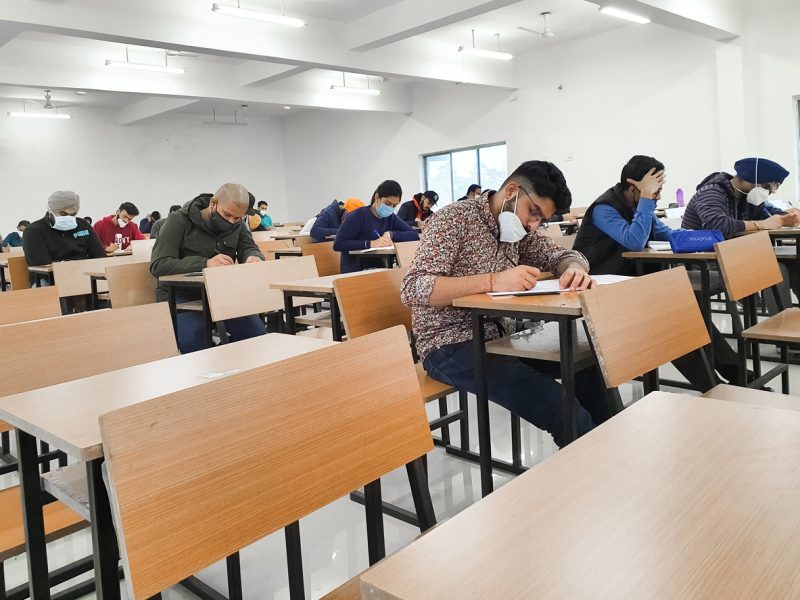

This has prompted the government to shift the criteria for selection to undergraduate courses from board exam scores to the Common University Entrance Test (CUET) in 44 central universities, including DU. Sixteen other institutions, such as the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and the National Rail and Transportation Institute, will also go by CUET scores for admission to their undergrad courses.

Would CUET lead to a more meaningful selection process in the universities and institutions that adopt it – in terms of testing cognitive capacities and aptitudes?

Let’s look at what benefits CUET currently offers.

What CUET offers

To the extent CUET is replacing a highly flawed selection process based on board exam scores, it is a welcome move. We are told that with CUET, board exam marks will count only as a necessary eligibility condition but not sufficient to ensure selection.

The second advantage is that CUET is offered in 13 languages. So a candidate from a regional language background in academics can also take a shot at it.

The third advantage is structural: unlike a board exam, a machine-corrected, multiple-choice questions (MCQ) format eliminates subjectivity.

That said, even for an aptitude test such as Kishore Vaigyanik Protsahan Yojana (popularly, KVPY), which has no prescribed syllabus, coaching institutes offer programmes to aspiring students to ace the test that leads to generous scholarships. It is extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible, for any candidate in India to clear entrance tests for undergrad programmes without the help of coaching institutes. And, unfortunately, coaching institutes typically focus on pattern cracking and not on helping students fill gaps in learning.

So, within a short time, CUET will face the danger of becoming yet another stress-inducing choke point for students which the coaching institutes and factory-schools will thrive on. To avoid this, we need a CUET that focuses on testing learning and not recall and pattern-cracking.

Given that CUET is likely to attract an increasingly larger number of universities, institutions, and candidates, a test that can be scored by a computer, with minimal human intervention, is a natural choice. MCQ format, howsoever flawed it is, selects itself as the most suitable. CUET has negative marks for wrong answers to prevent wild-guessing.

Making MCQ format effective

So within these limits, how can the MCQ format be made into a more effective testing tool than it is now?

Well, an MCQ-based test could have questions that test mere information recall such as ‘what is the formula for the area of a circle? (πr^2)’ or ‘When was Telangana formed? (June 2014)’ All that is tested here is the candidate’s familiarity with a particular piece of information.

At a slightly higher level, it could also have questions, particularly in sciences and mathematics, that test application of information such as ‘A car skids 20 meters with locked brakes if it is moving 40 km/hr. How far will the car skid with locked brakes if it is moving at 90 km/hr?’ Or ‘How much water can a cylindrical drum of 1-meter height and 40 cms diameter contain?’. The candidate should know how to calculate based on either information given or formulae (s)he is expected to recall.

Both these types are within the scope of the high-fee charging coaching industry.

A less explored option

But there is a third, but not a well-explored option.

Consider this question: You are given 10 lemons and asked to calculate (approximately) the amount of juice they will yield without cutting or squeezing any of them. Which of the following options would you use? You may tick any number of options, but inappropriate choices will carry negative marks.

a) use a bucket filled with water b) put a lemon between two blocks c) use a measuring cup d) use a ruler to measure length e) use sampling f) use statistics g) use mathematical modelling h) make an assumption

Here, based on understanding, creative application and thinking are being tested and not mere recall and application of formulae. Sure, these questions will demand more time to answer – so the typical emphasis on speed in MCQ-based testing would have to be reconsidered. However, it is possible to use even a machine-corrected MCQ-based test to gauge thinking and understanding.

Another interesting MCQ format could be to offer lots of – say 10 or 15 – answer choices to a question – not just 4 or 5. Some of the choices could be correct, and some wrong. Even in a question with a few choices, having more than one correct answer might be a tool to test learning. There are many more ways of enhancing the quality of an MCQ-based test format.

Constant effort

Of course, the coaching industry would try to take a shot at cracking patterns even in such MCQ formats meant to test critical thinking abilities. However, it might lie outside their ambit – at least in the near term. The challenge is in regularly coming up with new designs for such meaningful tests to stay ahead of the pattern-cracking experts. This would require a constant, high-quality effort on the part of the National Testing Agency (NTA), which sets the questions for CUET. A small team, dedicated to probing thinking abilities and aptitude, should do the trick.

There is at least one potential disadvantage for underprivileged students, though. They usually focus on scoring well in the board exams. Now, if a student’s score in the Class XII board exam is not going to fetch him/her a seat in desired courses, and if (s)he had not got the opportunity for high-quality training or learning required to crack CUET, then aren’t we condemning the person to go for a poor-quality undergrad education? How to make CUET equitable to aspirants from a variety of geographies and socioeconomic backgrounds? There are no easy answers to that question.

(The author consults in the education domain. He can be reached at srihamsa@gmail.com)