Effectively reducing methane in air can wind back global warming by 15 years

Carbon dioxide emissions from energy and transportation have long taken center stage at United Nations climate summit negotiations. But here at COP26, in cold, rainy Scotland, methane, a far more potent heat-trapping gas, is grabbing a share of the spotlight for the first time.

With good reason.

Methane only exists at roughly 2 parts per million in the atmosphere, compared to 412 parts per million for CO2. But the methane molecule (CH4) traps as much as 85 times more heat than the more abundant polluting CO2. But while carbon dioxide remains in the sky like a warming blanket for hundreds of years, methane largely dissipates in roughly a decade — making it a ripe target for nations to attack in their effort to slow the ominous quickening pace of global warming.

As the all-important Glasgow summit enters its second and final week, potential real progress came on November 2 when an alliance of some 100 countries, led by the U.S. and European Union representing two-thirds of the global economy, pledged to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

But China, Russia and India, major methane emitters, refused to join, a stark reminder of the political obstacles always in play during climate negotiations.

And importantly, last week’s COP26 methane pledge is voluntary, legally non-binding, and has no enforcement provisions, meaning that it could suffer from the same weak U.N. rules that have plagued CO2 and CH4 reporting in the past, which has allowed the world’s nations to drastically underreport their greenhouse gas emissions. Examples were revealed in a bombshell Washington Post investigation that documents various national cheating strategies (some major emitters haven’t even filed reports in more than a decade).

The Washington Post investigation primarily looks at CO2 underreporting, but it also examines methane, finding that: “methane emissions comprise a second major portion of the missing greenhouse gases in the U.N. database. Independent scientific data sets show between 57 million and 76 million tons more of human-caused methane emissions hitting the atmosphere than U.N. country reports do. That converts to between 1.6 billion and 2.1 billion tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions.” This underreported methane is mostly arising from the oil and gas industry, agriculture (especially cattle), and gigantic landfills.

Clearly, immediate methane action is needed.

According to the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), if the world has any hope of keeping global warming to a 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit) rise over pre-industrial levels — the Paris Agreement target — and avoid the worst impacts of climate change, then methane releases must come down by at least 45% by 2030. And those severe cuts must be combined with equally intense efforts to reduce CO2 emissions, halt deforestation and protect ecosystem biodiversity.

That’s a lot to get done among 196 often argumentative nations who in 26 annual COP meetings have failed to pull together on any legally binding agreement as the climate crisis has deepened into what U.N. head Antonio Guterres has called “code red for humanity.”

Methane removal hope

Into this daunting international cacophony steps Daphne Wysham, chief executive of Methane Action, a new non-profit based in Washington state. She represents a coalition of earth scientists devising compelling but yet unproven ways to accelerate the pace of methane removal from the atmosphere, something she says is critical because methane reductions among nations will not be enough to bend the warming curve.

That’s why Wysham is in Glasgow. In its September report, the IPCC for the first time acknowledged that methane removal technology could be an important tool in climate change mitigation, with the IPCC citing the research of two well-known scientists affiliated with Methane Action; one a board member, and the other a scientific advisor.

Methane was barely a concern in Paris in 2015; it is now because levels of the greenhouse gas have been surging for a decade.

“This is all so new,” Wysham told Mongabay. “I’m here to talk to as many people as possible and tell them there is this potential for methane removal that isn’t on anybody’s radar.”

Wysham and her group are getting noticed at COP26, where she hosted a well-attended virtual side event. She also co-authored a Washington Post op-ed last week with Stanford earth scientist and colleague Rob Jackson, a leader in the field. The journal Science wrote approvingly, with caveats, of Methane Action’s and other researchers’ ideas. Funders are reaching out, too. And she has a meeting this week with the U.S. State Department’s climate team.

Wysham explained why she is garnering so much attention: “There is no way we can meet the Paris target without addressing the methane problem coming from fossil fuel production, landfills and agriculture. Even with what’s on the table now, it will not allow us to meet the 1.5° C goal. We need to try to do more.”

How it (might) work

Despite its small concentration in the atmosphere compared to CO2, methane, scientists say, accounts for about half of the 1.1° C of warming to date. But Jackson, at Stanford, says that effective methane removal strategies could reduce that atmospheric concentration to pre-industrial levels, trimming as much as 0.6° C of current warming.

In the gloomy world of climate action, that qualifies — if and when it works — as hope.

Jackson told Mongabay that methane in the air eventually breaks down into carbon dioxide, which by comparison traps far less heat. “[Technological] methane removal methods accelerate what nature does over years — [more quickly] oxidizing methane to carbon dioxide,” he said. Researchers are testing a variety of methane removal methods.

Jackson says most methane is oxidized by free radicals in the air such as hydroxyl and chlorine. Scientists are looking at ways of using iron-salt aerosols to try and increase the abundance of chlorine “in a parcel of air to oxidize the methane contained in it.”

Another idea, which Jackson favors, oxidizes methane in combination with emerging carbon-capture technology. “I like the idea of combining direct-air capture of CO2 with methane removal, moving air through a system once, but removing more than one greenhouse gas from it,” Jackson said.

The up scaling and implementing of such technologies clearly faces challenges, such as the difficulty in moving experimental methane removal techniques out of the lab and into Earth’s atmosphere.

Jon Shepard, climate program director for Global Development Incubator, a US-based non-profit, has been following the emergence of Wysham’s Methane Action and its proposed methane removal methods with interest. One promising line of research he described to Mongabay is being tested at the University of Copenhagen where laboratory researchers have mixed iron chloride with methane and observed it as it turns into carbon dioxide.

The process works. The innovative but as yet untried plan would be to attach an iron chloride reservoir to the smokestacks of container ships at sea for injection via their exhaust plumes into the atmosphere. The plume, theoretically, would carry the iron chloride into the air and speed up methane oxidation.

That would require a lot of container ships, right? Shepard said perhaps not.

“The plume of a container ship spreads out within a week to cover 1% of the earth’s surface; one ship,” he explained in Glasgow. “The question isn’t will [the iron chloride plume] go far enough, it’s how long will it [stay] in the air? The iron chloride would likely be rained out the plume within a day to two weeks. This is potentially a very localized, controllable thing that can be turned off.”

Researchers, including Jackson, question whether the iron chloride molecules would come into contact with sufficient methane molecules, and liken the various proposed technologies of methane molecule removal from Earth’s atmosphere to “pulling a needle from a haystack over and over again.”

In a recent interview with Mongabay, Shaun Fitzgerald, an engineer at the University of Cambridge in England, described another carbon removal model he is developing: using titanium dioxide paint, which in the presence of the sun’s ultraviolet rays, oxidizes methane on contact in what’s called a photocatalytic conversion.

“One idea is to use fans to blow a lot of air over solid [painted] surfaces, but that would take a lot of energy,” Fitzgerald said. “Or, you could save on energy and apply the paint to things that are moving, like vehicles, airplanes, the blades of wind turbines. So, you aren’t asking the air to move to a solid surface; [instead] you’re moving the solid surface through the air. That’s what I would really love to do.”

Thawing permafrost which has caused major surface subsidence here on Herschel Island, Yukon, Canada, 2013. The rate of permafrost melt, and methane released from it, is escalating as the world warms. Image by Boris Radosavljevic found on flickr cc-by-2.0.

From fantasy to applicability

Hearing about such engineering ideas for the first time can strain credulity — and create worries about what unforeseen environmental side effects might occur.

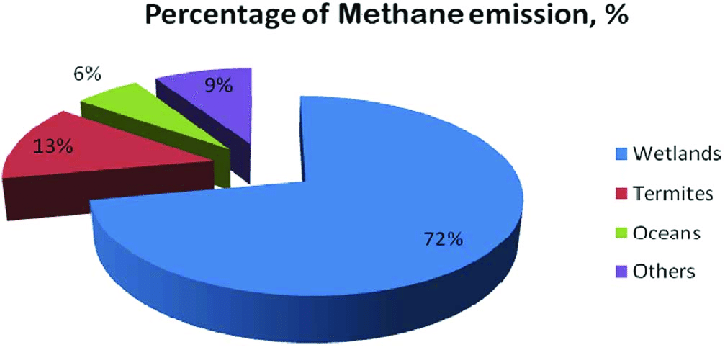

Wysham gets that, as do Jackson and Shepard. But it is a testament to how bad the climate crisis has gotten that such ideas are garnering serious attention at COP26. There is a looming fear that methane emissions could explode this decade, as Arctic permafrost thaws and wetlands degrade — as both are doing — releasing massive amounts of soil-stored methane and causing global temperatures to soar.

“Honestly, we are at the point where we need to try not everything, but more or less everything,” Shepard said. “The radiating impact of methane is so great that anything that can safely and controllably remove it from the atmosphere by accelerating a natural oxidation process — bring it on.”

Jackson was quick to emphasize the many hurdles to jump: “Assuming methane removal works, the biggest challenge will be scaling technologies to the global atmosphere. We only have to remove millions of tons of methane to make a difference in temperature, compared with billions of tons for carbon dioxide. But methane is also 200-times less abundant in the atmosphere. So you have to process more air to remove a ton of methane.”

Also read: Europe’s tryst with biofuels destroyed 10% of world’s orangutan habitats

There’s also the problem of getting the world’s nations to agree to, and pay for, an emergency crash program for methane removal research and implementation.

But the payoff, Shepard said, could be enormous: “If you take a molecule of methane and oxidize it into a molecule of CO2, the [heat trapping] impact of the C02 is just 1/44th the impact of the methane that went in. That’s the number to focus on.”

He openly acknowledged there are risks to consider to public health and the environment. Of the strategies he’s reviewed, if they indeed work at the scale required, each seems to pose minimal risk. But of course, that won’t be fully known until these methods are tried in nature.

The biggest challenges now remain money and time. Wysham says she projects needing anywhere between $5 million and $50 million to fund the research underway for proof of concept. She envisions the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or Department of Energy eventually funding and evaluating the most promising avenues of research.

However, one need only to look at the failed promise of algae biofuel — a silver bullet for combating climate change that achieved heavy U.S. funding in past decades — to understand how very promising but speculative hi-tech solutions can fizzle.

Shepard agrees that, once the technology is operative, that verifying the total amounts of methane actually being removed from the atmosphere, will also be difficult. Discussions are underway with Verra, an independent nonprofit that monitors and verifies carbon offsets and emission reductions, to devise a verification process for removal.

Also read: Not enough to slash carbon emissions, vital to deplete stock of emitted CO2

As for timing, Wysham believes that with adequate funding and some luck, methane removal could start in five or 10 years. Jackson is more cautious. “We only have 20 to 30 years to help keep global temperatures below 2° Celsius,” he said. “Here’s one scenario: roughly a decade to work out the methods, a decade to deploy them, and a decade to remove the methane at scale before 2050.” Certainly, this is a horserace humanity could lose — but the researchers argue we must try.

Shepard warned that nothing is assured when moving scientific theories from the lab to the real world, but he stressed, “If it becomes possible to do this at scale — removing hundreds of millions of tons of methane from the air per year — you could effectively wind back global warming by 15 years. That’s worth going after.”

(The article first appeared on Mongabay)