English nationalism wins the day for Boris Johnson

In the end it was a Brexit election. Boris Johnson’s gamble, three months into his term as Prime Minister, to find a way out of a deadlocked Parliament that thwarted his Withdrawal Agreement by seeking a fresh vote to rally the Leave-voters behind him, has paid off handsomely.

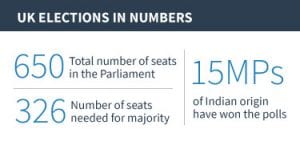

In the end it was a Brexit election. Boris Johnson’s gamble, three months into his term as Prime Minister, to find a way out of a deadlocked Parliament that thwarted his Withdrawal Agreement by seeking a fresh vote to rally the Leave-voters behind him, has paid off handsomely, with his party winning 365 out of 650 seats, after all seats were declared.

And what a spectacular landslide it has been!

The Conservative juggernaut has rolled on into what was once thought of as seemingly impregnable “Red wall“ of Labour strongholds in North Wales, Midlands and northern England. Constituencies in the former mining towns and industrial areas of northern England – the traditional Labour strongholds- such as Blyth Valley, Great Grimsby, Workington, Darlington, Durham and even Tony Blair’s former seat of Sedgefield have fallen to the Conservatives in what many commentators are terming as “ political earthquake” and a defining election comparable to the 1979 election win of Margaret Thatcher or the 1997 win of Tony Blair.

So how did it happen?

Let us put it simply: the Brexit divide drew the battle lines; the Leave-leaning English votes polarised around Tories while the Remain-votes got scattered between Labour, Liberal Democrats and the SNP.

Labour had a peculiar problem.

Also Read: Indian diaspora hails Johnson’s resounding victory in UK election

Labour’s blue-collar and working-class supporters in northern England who were its backbone, had voted Leave in 2016, while its metropolitan, big city based Liberal supporters in multicultural cities like London had voted Remain.

During the 2016 referendum, Corbyn had campaigned for ‘Remain in a Reformed Europe’ but it did not cut much ice.

Labour did not seem to have learned from that mistake and the amends it made this time did not go far enough either.

Under pressure to keep the Labour voting Leavers and Remainers in his fold, Corbyn offered a middle way – renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement and place it before the electorate for a second referendum. He also tried to widen the scope of the electoral agenda by including other issues such as NHS funding, poverty, education etc.

The message was so convoluted it did not cut across. In fact, during the TV debates between Johnson and Corbyn, this became a useful point for Johnson to ridicule and pillory Corbyn.

In contrast, the Tories under Boris Johnson had a short, focussed slogan to “Get Brexit Done” which he repeated over and over again to the exclusion of other issues and drove home the message. Just like his earlier slogan “ Take Back Control” during the 2016 referendum, this also appealed to a sense of English nationalism in the small towns and the countryside that had nursed a feeling of neglect and alienation with economy stagnating outside the bubble of London. The EU became a useful scapegoat for the problems plaguing Britain.

In his speech on Friday morning after the scale of the victory was known, Johnson said Brexit, “… is now the irrefutable, irresistible and unarguable” decision of the British people and it would be done.

He is only partly right. Though he has won the mandate in a First Past the Post electoral system, Remainers point out that the votes in favour of the two pro-Leave parties (the Conservatives and Brexit Party) put together is only around 45 % while the vote of all the other pro-Remain parties including Labour and LibDems is higher at around 50%. But that is an argument that has very little legal force or political validity now.

Also Read: Boris Johnson wins majority in UK’s Brexit election

Boris now has a huge mandate under his belt and is not beholden to the Conservative Eurosceptics or the Northern Ireland unionists for survival, unlike Theresa May. There is hope in some circles that he would rule as a “metropolitan, liberal and One Nation Conservative”, like he did when he was Mayor of London, rather than as a hard Brexiteer.

Whether those hopes would prove to be true remains to be seen.

Boris has pledged to get the UK out of the EU by January 31, which seems certain now.

But the bigger task for him would be get a long-term trade deal with the EU, that would protect the UK business and industry.

Leaving the EU would also give him the freedom to strike free trade deals with countries like India and USA but there are trade- offs to be made in such efforts.

(India, for instance, would want a more liberal visa regime for its IT professionals while USA would demand better access to NHS for its pharmaceutical majors. These are potential minefields and it remains to be seen how Boris navigates these issues.)

Will Scotland break away?

On the political front, the Tory win still leaves important questions over the future of the UK. The nearly three-hundred-year political union between England and Scotland will again be tested with the Scottish National Party (SNP) raising the battle cry for a second referendum for independence for Scotland.

The SNP has been strengthened by its equally impressive win in Scotland this time – winning 48 out of the total 59 seats there.

Nicola Sturgeon, the SNP leader and the First Minister of Scotland, has already said her government would again seek permission from London for a second referendum.

Boris Johnson has predictably rejected the demand for another referendum for Scotland during the campaign, pointing out that such independence referendums are held “once in a generation” and not every few years.

Also Read: UK’s Jeremy Corbyn says will not lead Labour at next election

The SNP argument however is that Scotland has voted Remain in 2016 and in this election also it voted for a Remain argument. With the rest of the UK deciding to leave the EU, the democratic way out would be to allow a second independence referendum for Scotland.

This seems a difficult conundrum for now which is likely to lead to what political observers call a “constitutional clash”.

(Northern Ireland problems may also come back to haunt the new government, with the Brexit deal failing to satisfy the rival nationalist and unionist camps there.)

Labour faces change of guard

The elections results would inevitably lead to a change of guard in the Labour party; Jeremy Corbyn has indicated he would not be leader of the Labour party in the next general election and would go early next year, but his foes within the party would like him to go sooner.

The Labour party has veered to the Left from the middle ground it occupied during the Blair-Brown era. The battle for the party leadership, likely early next year, would indicate which way the party would go.

(The Liberal Democrats who started the campaign with a decent vote surge in their favour, have had their worst result, with their leader, Jo Swinson, losing her seat in Scotland narrowly. The hardline Brexit Party under Nigel Farage has drawn a blank but Farage maintained a brave face saying the party had “used its influence” in avoiding a second referendum.)

Also Read:

The Brexit debate over the last four years has deeply divided the country. It was left to Boris Johnson, in his speech from Downing street, to appeal to the people to “find closure and let the healing begin”. He said the country “deserved a break from wrangling, a break from politics and a permanent break from talking about Brexit”. That is a statesman-like talk; but Britain’s journey out of EU seems long and fraught.

(The writer is a senior journalist and commentator based in London.)