Nuclear energy gets a seat at COP26 table; to be part of solution to climate change

Just before the Glasgow Summit got underway, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) released a document last month arguing that nuclear power can help deliver the goals of capping global warming at 1.5 degree Celsius as agreed upon in the Paris Agreement. Warning that “time is running out to rapidly transform the global energy system,” as fossil fuels still continue to dominate in electricity generation, the agency advocated the roll-out of more nuclear power stations.

Just before the Glasgow Summit got underway, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) released a document last month arguing that nuclear power can help deliver the goals of capping global warming at 1.5 degree Celsius as agreed upon in the Paris Agreement. Warning that “time is running out to rapidly transform the global energy system,” as fossil fuels still continue to dominate in electricity generation, the agency advocated the roll-out of more nuclear power stations.

The 24-page UNECE report highlighted how only hydropower has played a greater role in avoiding carbon emissions over the past 50 years. However, making a strong pitch for nuclear power, the report said nuclear is a low-carbon energy source that has avoided about 74 Gt of CO2 emissions over three decades, and nearly two years’ worth of total global energy-related emissions, it noted.

“Nuclear power is an important source of low-carbon electricity and heat that can contribute to attaining carbon neutrality and hence help to mitigate climate change,” said UNECE Executive Secretary Olga Algayerova at the time of the release of the document. The document also quoted a 2018 report by the Inter-Governmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), which stated that the demand for nuclear generation will increase six times by 2050, with the technology providing 25 per cent of global electricity.

One of the conclusions of the report was that decarbonising energy is a significant undertaking that requires the use of all available low-carbon technologies and world climate objectives will not be met without nuclear technologies.

Significantly, at the COP26 Glasgow summit too, there was a marked shift in the attitude towards nuclear energy. According to an AFP report, nuclear energy was given a seat at the table for the first time in this COP26. (At the 2015 climate summit in Paris, nuclear was shunned)

With the deepening crisis over global warming and the urgent need to reduce the use of fossil fuels, there has been a notable change and nuclear was being welcomed with open arms, said an AFP report. And quoted IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi in the article, who said that “nuclear is not only welcome, but is generating a lot of interest” at the summit.

Also read: COP26 turned into a PR event, it’s a failure: Greta Thunberg

In September, Grossi while addressing an IAEA conference in Vienna, stressed the importance of the work of the IAEA to ensure that nuclear energy “is and must be part of the solution to climate change.” And how it already accounted for a quarter of the clean, carbon free energy worldwide.

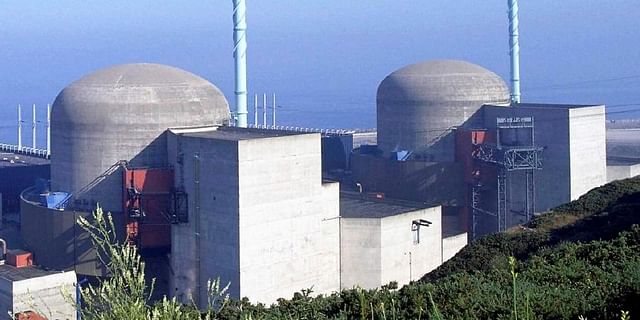

There are 444 nuclear power reactors operating in 32 countries today, supplying around 10 per cent of the world’s electricity and more than a quarter of all low-carbon electricity. An additional 50 reactors are under construction in 19 countries, which are expected to provide additional capacity, he said.

He had added, “In every scientific based projection, global decarbonisation for 2050 is possible, and will be much easier, with nuclear energy.”

Nuclear energy however comes with baggage. The memory of Chernobyl and Fukushima continues to haunt the world. The meltdown of three reactors at Japan’s Fukushima power plant in 2011 after an earthquake and a tsunami made people nervous about nuclear.

Opponents dubbed it as too expensive, too risky and totally unnecessary. Building a nuclear power plant can be a discouraging proposition for stakeholders, with conventional reactor designs turning into multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects. High capital costs, licensing and regulation approvals, coupled with long lead times and construction delays, have also deterred public interest. But some countries, most notably China, are building new reactors, others are shuttering old ones: 5.5 gigawatts of capacity were installed worldwide in 2019 while 9.4 GW were permanently closed, said the IEA.

There is also the thorny problem of disposing of highly toxic waste and decommissioning power stations. However, UNECE warns that to prevent radiological accidents and manage radioactive waste, risks must be properly anticipated and handled. Some countries choose not to pursue nuclear power because they consider the risks to be unacceptable.

Yet, the damaging fallouts of climate change, including rising sea levels, droughts, fires, extreme weather events, ocean acidification etc., have helped generate fresh interest in the potential for nuclear power.

Moreover, Grossi pointed out that statistically the technology has fewer negative consequences than many other forms of energy and championed it as a complement to renewables. “Nuclear energy goes on and on for the entire year, he said, quoted AFP.

On the time it takes to build nuclear power stations, which may be too late to challenge global warming Grossi said he thinks part of the answer lies in keeping existing reactors working. A number of countries – such as Canada, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Russia, Ukraine, the UK and the USA – have explicitly stated that nuclear power will play an important role in reducing their national emissions in the future. While Belgium, New Zealand and Germany have announced phasing out nuclear power, in 2025 and 2023 respectively.

India’s largest nuclear power plant project in Maharashtra with French energy giant EDF had been blocked for years by nuclear events and local opposition. But it seems to have got a second wind and India reportedly seems closer to realising the project. Once completed, the facility would provide 10 gigawatts (GW) of electricity, roughly enough for 70 million households. Construction is expected to take 15 years, but the site should be able to start generating electricity before its completion, said media reports.

Meanwhile, US and Canada are opting to build “small modular reactors” since they offer a lower initial capital investment, can be scaled up or down to meet energy demands and help power areas where larger plants are not needed. SMRs can also be used to help replace or repower retiring power plants or to complement existing power plants with zero-emission fuel.