- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Why the risk of earthquake in Bengaluru could be rising

In Delhi-NCR, the done-to-death joke about earthquakes is that when people feel the tremors with their beds, ceiling fans and chandeliers shaking, they quickly log in to Twitter to confirm if people have begun posting with the hashtag earthquake instead of rushing out to ‘save themselves’. But thousands of kilometres away in Bengaluru, one actually has to step out to see why beds, fans...

In Delhi-NCR, the done-to-death joke about earthquakes is that when people feel the tremors with their beds, ceiling fans and chandeliers shaking, they quickly log in to Twitter to confirm if people have begun posting with the hashtag earthquake instead of rushing out to ‘save themselves’. But thousands of kilometres away in Bengaluru, one actually has to step out to see why beds, fans and chandeliers rarely shake like they do in the National Capital Region.

The answer to why Bengaluru is quake-proof is most visibly clear in Lalbagh Botanical Garden, which flaunts a rich collection of tropical and subtropical plants, including several centuries-old trees. The sprawling park, spread over an area of 240 acres in the heart of the city, has a beautiful glasshouse surrounding a sprawling lake.

Visitors to the Garden are offered a visual and historical treat of a Bonsai Garden, Kempe Gowda Watch Tower, Hibiscus Garden and Big Rock. It is the Big Rock that ensures Bengaluru is safe from earthquakes as the region rests on this rock showing up a glimpse in Lalbagh Garden.

There is no historical proof suggesting Kempe Gowda, a chieftain under the Vijayanagara Empire, knew about the importance of the rock, but some say he built the Kempe Gowda Tower so that his guards could keep an eye on the rock and protect it from encroachments. The more popular theory however is that the tower was built for military reasons.

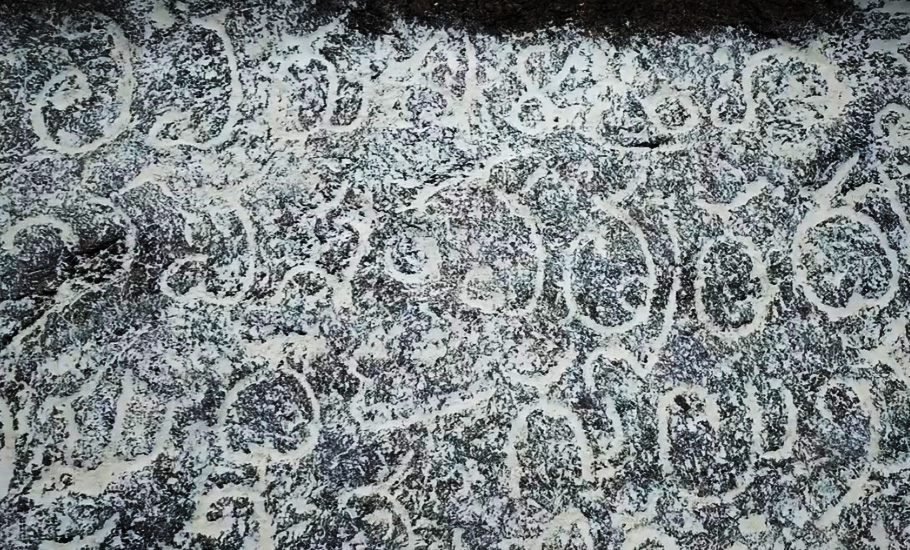

The rock, also called a Peninsular Gneiss — a mixture of granite rocks — are widespread around the Deccan Plateau. The gneiss is exposed in Lalbagh Botanical Garden, where Kempe Gowda built a Watch Tower to watch over the enemies, but which inadvertently helped to watch over the gneiss protecting Bengaluru too.

But recent encroachments and construction activities could increasingly be putting the rock base at risk and making Bengaluru prone to earthquakes.

Bengaluru region is not safe from earthquakes. Arkavati plate, on which the city and surrounding districts sit, has developed active faults, leaving the region at the risk of earthquakes. Such quakes, scientists say, would be of low magnitude, but they will be there.

According to the experts at the Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre (KSNDMC), the seismic hazard map of India puts Karnataka in Zone II ‘least active’ and Zone III ‘moderate’. Coastal and northern-interior districts bordering Maharashtra fall in Zone III. The rest, including Bengaluru region, lie in Zone II.

According to data from 2019, the Arkavati plate, on which Bengaluru and its surrounding districts sit, has developed active faults, leaving the region at risk of low-magnitude earthquakes. Studies found several active faults have been identified in Chitradurga, Bhatkal, Udupi and Bengaluru regions as well.

On November 13, 2018, a 1.6-magnitude quake was recorded at our Chitradurga observatory. Five years before that in 2013, Chitradurga recorded seven quakes.

“Thousands of high-rises have sprung up since 2000, following the Information Technology boom started in the city. Builders are using the latest technology to dig borewells. Almost every building has separate borewells. The cracks and holes being made by drilling machines into the earth, are impacting the rock layer and also removing moisture from the soil. In the long run, this will exhaust the entire groundwater in the area and make the rock layer vulnerable to tectonic movements and earthquakes,” said urban expert Dr Ravindranath Bhat, a retired officer with the state Karnataka State Department of Archaeology.

With Metro rail projects, flyovers and subways in every corner of the Bengaluru, the construction work is happening at an unprecedented pace. Experts fear the powerful blasts being carried out for making tunnels and high-rises could increase the vulnerability of the rock beneath, which protects the 7.5 crore population of the city, acting as a solid edifice.

The last time micro-tremors were felt in some parts of Bengaluru was in 2018. The recent earthquakes have all been of low magnitude.

“The negative impact will be seen in five to 10 years,” said Vinay Nadig, an Earth Science Research Fellow at Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru.

Rules are being flouted, but the authorities have turned a blind eye to the whole problem.

“There are rules and regulations within the framework of law. But the rulers are just seeing development through construction. There are open violations of several urban Acts, but no one is bothered,” said urban activist Alvin Mendonca.

The monolithic hill rock, which is 3,000 million years old, is a hard rock formed from igneous (having solidified from lava) rocks. Since Bengaluru stands on this layer, its foundations are strong acting as a bulwark against major earthquakes. “This one nice stone has safely carried the burden of whole of Bengaluru,” renowned botanist Vijay R Thiruvady, told The Federal.

“Perhaps, Kempe Gowda, who is known for developing Bengaluru, realised its importance. He realized how strong a city he was building and so the first Kempe Gowda tower was established at the foot of this hill,” Thiruvady said.

It isn’t just Bengaluru which is protected due to the rock, but such rocks protect a large part of south India.

“It is said that due to the presence of such hard rocks in south India, huge earthquakes do not occur in this region. The Lalbagh rock is the main attraction of this garden. It is a National Geological Monument and is the oldest rock in the world,” he said.

The Geological Survey of India’s studies in the Fundamental and Multidisciplinary Geosciences and Special Studies, and its specialised investigation on earthquake geology points out that the Peninsular Gneiss National Monument at Lalbagh is composed of dark biotite gneiss of granitic to a granodiorite composition containing streaks of BioLite. Vestiges of older rocks are seen in the form of enclaves within the gneiss.

Columnar Basalt Lava, St. Mary’s Islands, Udupi District, Karnataka multi-faced columns developed in the basalts of Deccan trap. It says that the Pillow Lava, containing pillow-shaped structures that are attributed to the extrusion of the lava underwater, or subaqueous extrusion, in Karnataka is one of the best of its kind in the world and helps in preventing earthquakes.

“Karnataka has no history of any massive earthquakes, but the state had felt the impacts of earthquakes that took place in Indonesia or elsewhere,” said Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre director VS Prakash.

But Bengaluru did have an earthquake in 1507. “Historical evidence suggests there was an earthquake in the Bengaluru region in 1507,” Dr Yuvaraj K, a researcher from Bengaluru University said.

British historian BL Rice, who found an inscription at Billanakote in Nelamangala, which is around 40 km away from Bengaluru, elaborated on the inscription. “In that inscription, one Veerayya had written about the earthquake that took place, but nothing happened because of the peninsular gneiss,” he said.

an inscription in Billanakote in Nelamangala, which is around 40 km away from Bengaluru, elaborated on the inscription

He too, however, said that the peninsular gneiss, which is protecting Bengaluru is under threat because of several underground activities happening in and around the region.

“Such projects in the name of development are a danger to the rocky layer, which is protecting the city,” he said.