- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Why Tamil silent films are no longer heard of

In 1916, R Nataraja Mudaliar made a silent film called Keechaka Vadham. The movie, considered the first ‘Tamil’ silent film because all its actors were Tamils, barely has any evidence of existence left, because sadly, all prints of the film have been lost. Many other silent films made in the era too have been lost to time. Worse, we don’t even have a decent repository of reviews...

In 1916, R Nataraja Mudaliar made a silent film called Keechaka Vadham. The movie, considered the first ‘Tamil’ silent film because all its actors were Tamils, barely has any evidence of existence left, because sadly, all prints of the film have been lost. Many other silent films made in the era too have been lost to time. Worse, we don’t even have a decent repository of reviews to understand the history of silent movies today.

This has raised obvious questions over why journalists and writers in the 1920s didn’t give much importance to silent movies.

Most south Indian filmmakers of the silent era like A Narayanan, R Prakasa, Thomas Huffton among others, were influenced by the Hollywood style of film-making, according to Sugeeth Krishnamoorthy, an independent researcher who has brought in clarity with some interesting findings on the silent film era of Tamil Nadu. “They tried to localise the cinematic language which they saw and observed, including its commercial prospects in Indian themes and stories. One of those commercial aspects was normalisation of sex and violence in the narrative of the average Indian silent film. Many films were subjected to heavy censoring mainly due to sex and violence in them,” he tells The Federal.

Gajendra Moksham (1923), Sarangadhara (1930), Prameela Arjun (1930), Rose of Rajasthan (1931), The Sex (or) Sthri Shakti (1931), Devil and the Damsel (1931), Pride of Hindustan (1931), Vishnu Leela (1932) are some of the popular silent south Indian films, which were hauled up by the censor board and passed with endorsement, after removal of scenes, due to violence, sex and nudity.

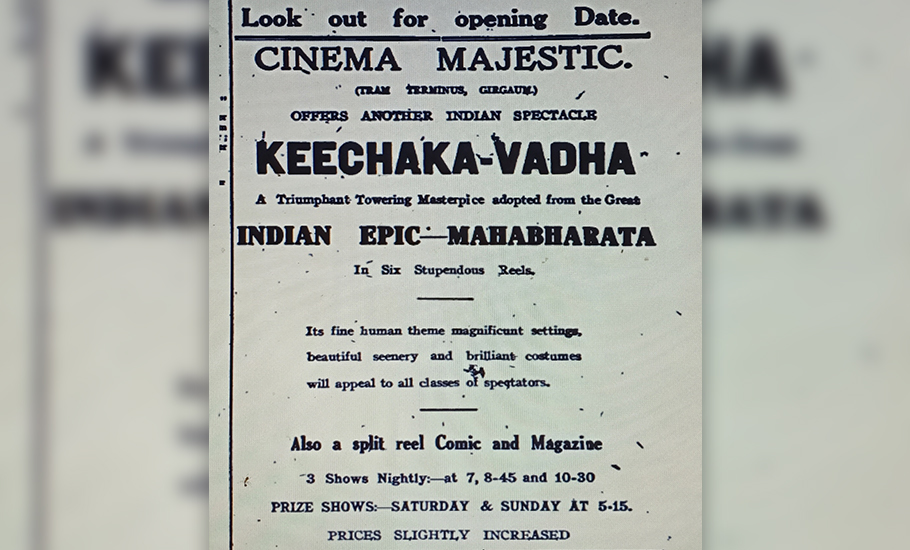

Even though journalists and intellectuals in Madras ignored silent films, some of them were screened across India, particularly in cities like Bombay and Calcutta. “Keechaka Vadham is commonly accepted as the first silent film produced in south India. There is hardly any reliable new information about this film that has sprung up in recent years. It is likely that the film was never reviewed, written about and published in south India, or that such a review may have been lost to time. But the film was screened all over the country. It made its way to Bombay in 1919, and was screened at the Cinema Majestic. In 1920, the film travelled to Calcutta renamed as Keechak-badh to suit the local taste,” said Sugeeth, based on the records that he received from the censor boards of the two cities. According to Sugeeth, SB Banerjea, a Calcutta-based film correspondent working for the English film magazine The Moving Picture World, saw the film and said “it has many defects”.

A large portion of the silent films were based on mythology and these aspects could have been easily avoided at the time of filming itself. “The silent films made in south India were very different from the sound films or talkies, at least with regard to violence and nudity.

The technology may have changed the film experience by bringing sound, songs and dance, but we need to find out how it changed the attitude of the silent era film-makers, who were themselves involved with the early talkies to make films for a holistic family experience,” said Sugeeth, who has been searching the lost reels of Tamil cinema since 2014. Based on the information that he collected, he released a documentary titled The Missing Film Reels of Tamizh Cinema (1916-2016) in 2018. The documentary chronicles the evolution of Tamil cinema over 100 years, focusing on ‘special’ films either considered permanently ‘lost’ or ‘missing’.

When Sugeeth went deep into the subject, he knew more about the ‘exhibition’ called silent cinema. “Silent cinema came as a package along with additional entertainment forms such as Sandow (Eugen Sandow, the renowned Prussian bodybuilder) showmen showing their physical prowess, and that dancers would come on stage for interim entertainment as the projector reels were changed. I don’t know whether conservative rural Indian society allowed women and children to be a part of this experience,” he said.

The experience that a moviegoer had during the silent film era attains significance here. Sugeeth said unlike the talkie theatre, the permanent silent cinema hall was not constructed exclusively for the screening of films. “It was just a place with a proscenium that could allow an individual, or group of individuals, to address a gathering of a few hundred people. It is well documented that ‘Variety Hall’ was the first permanent theatre which had been built by film exhibitor Swamikannu Vincent, for the purpose of screening silent films. But contemporary documents show that the hall was not exclusively used for that purpose,” he said.

The students of Government Secondary Training School of Coimbatore had enacted the stage play Manohara in Tamil as a fund-raiser for the poor boys at the Variety Hall. The hall was also used for political meetings in the 1920s, which would shape the political and social history of Tamil Nadu in the future. “While theatres like Gaiety and the Variety Hall may have been better planned and provided a much better viewing experience thanks to the names and reputations of the patrons involved, the viewer of the average cinema hall or touring cinema, may not have been so lucky,” said Sugeeth.

The police response and blocking the overcrowding of the ‘Gokhale Hall’, citing political reasons, evoked a sarcastic jibe from a moviegoer in his “Letters to the Editor” section of a leading English daily. Offering much detail of his traumatic experience, the anonymous moviegoer, mentioned the names of the theatres, the overcrowding, the lack of sanitation, and the construction of the theatres on both sides of the Buckingham Canal along with its consequent pungent odour, the lack of electric fans, the claustrophobic environment and the backdrop of the viral infection that was then raging in Madras.

Tamil writer and novelist Vai Mu Kothainayaki Ammal (1901-1960), recounts her experience of watching silent films. “When I was a child, some silent movie reels were screened in the elephant stable of our village… It was simply jam-packed… The space was filled to a point that one needed to hold one’s own breath. From 90-year-olds to infants barely 40 days old were crushed into one and another. It didn’t cost much to see the film, unlike today. An adult was charged an anna (one-sixteenth of a rupee) and a child, half an anna, for seeing the screening. One might say that there was a crowd gathering larger than even the Parthasarathy Brahmotsavam. It was a new experience.”

“The screen showed men walking, running and jumping. Scenes of the running train, tidal waves of the sea, movement of the ship and people engaging and disengaging from the stationary train… What more can I say? You know what older men and the youngsters said? For an anna, or a half, they have shown us truly what the pleasure of heaven is,” wrote Kothainayaki Ammal in a Tamil magazine.

During his research, Sugeeth found this first experience of the silent film was truly a novelty for every filmgoer. But once the novelty faded out, the experience of the filmgoer came to light. “Naradar Srinivasa Rao, the editor and publisher of the famous Naradar magazine of the talkie era, cites a bad experience that he faced, after the initial euphoria of watching his first silent film. Famous actors of the 1930s like TP Rajalakshmi and SD Subbulakshmi who spoke and wrote immensely about stage and the talkie, made passing references to the silent cinema experience, but it appears that it did not make any major impression on them to warrant a detailed documentation,” finds Sugeeth.

Distribution and lack of quality of films also added to the trouble. “The Indian Cinematograph Committee (ICC) reports mention that most of the average exhibitors (unlike the big ones) had no choice of films. They just screened what was made available to them by the distributor who would block-book films. In most cases, even he had little control over the choice of films,” he said. “Most of these films, particularly the Indian films screened, were cheap and second and third round screeners with poor quality and innumerable scratches. Obviously, it would show out in the display of the film on the screen, hampering the user’s experience. Above all, the screening of films was not very profitable. Ownership of these screeners would change hands quite often.”

The study on silent film eventually led Sugeeth to the forgotten Kunhappu Brothers — Kunhappu Antony Davies and Kunhappu Antony Francis — who were bankers, film financiers, exhibitors and film distributors. “They were instrumental in building several institutions in Kerala’s Thrissur, and their role continues to be acknowledged locally, even today. Their most important contribution to silent cinema was that the brothers provided the seed capital to finance A Narayanan’s ‘General Pictures Corporation’ and ‘Exhibitor Film Service’,” he said.