- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

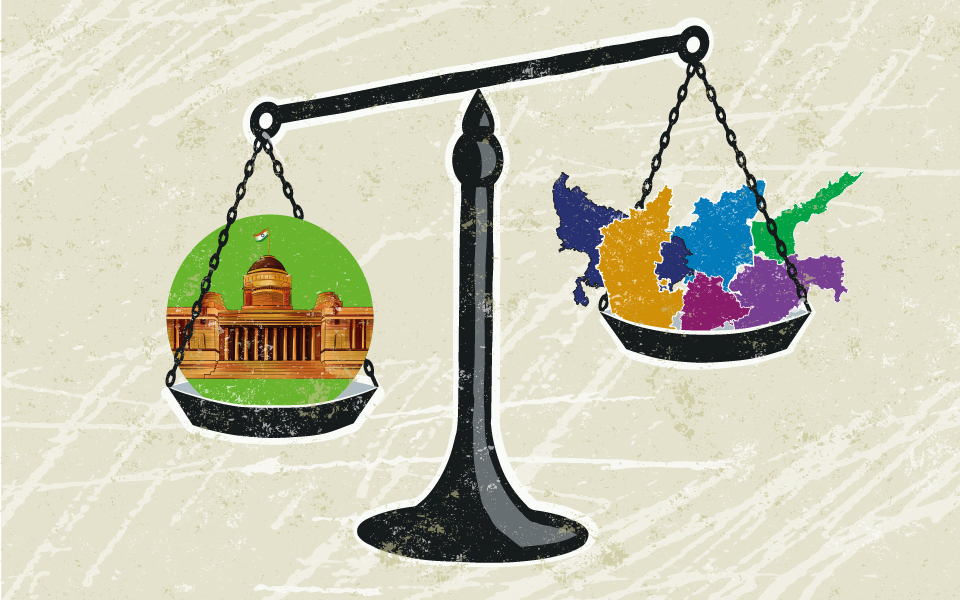

What Modi 2.0 means for India's federal system

“It is a matter of great concern that the federal structure of our Republic has come under increasing strain, contrary to the spirit of our Constitution, merely to suit the whims and fancies of the rulers in Delhi.” — Narendra Modi That was 2012. The Indian Republic, according to the then Gujarat CM, was being run in the form of a “family-run corporation that had all...

“It is a matter of great concern that the federal structure of our Republic has come under increasing strain, contrary to the spirit of our Constitution, merely to suit the whims and fancies of the rulers in Delhi.” — Narendra Modi

That was 2012. The Indian Republic, according to the then Gujarat CM, was being run in the form of a “family-run corporation that had all the potential of leading India to chaos and destruction”.

Lamenting the “systematic disruption of our country’s federal structure”, Modi perhaps never thought that his critique of the UPA government would some day be used to describe the “whims and fancies” of a government at the Centre that is now run by him.

Fast forward to 2019, it’s PM Modi who is facing the heat from his political opponents (already a fast dwindling number) who are screaming their lungs out about the “murder of democracy and federalism”.

On August 5, all hell broke loose as Home Minister Amit Shah announced the Centre’s decision to scrap the special status to Jammu and Kashmir guaranteed under Article 370 of the Constitution.

DMK chief MK Stalin called it a “dark day in the history of Indian federalism”. Some others called it a “reckless assault on federalism and democracy”.

How grave is this ‘threat’ and ‘assault’?

Threat to federalism is more than just brute parliamentary majorities drowning out opposition din. Recent decisions by the Modi government — a series of laws passed in Parliament in record time this session — seem to have changed the definition and understanding of the term federalism, with more power vested in the Centre, tilting the balance away from states.

Put simply, federalism is about statutory division of powers between states and the Centre. Its limited definition would suggest sharing of constitutional and legislative powers: While there are areas of legislation which fall under either state government or Centre’s purview, there are some areas in which both governments play an equal role. In its broadest sense, federalism, according to some academicians, also safeguard economic, social, political and cultural interests of a wide section of people. But what if these norms are violated through a straightjacketed approach in the name of a “united” and “strong” nation?

On the face of it, the Centre’s decisions — repealing of Article 370, proposed ‘one nation, one ration card’ scheme, the Union cabinet’s nod for ‘one nation, one tribunal’, the PM’s idea of ‘one nation, one election’, the RTI (Amendment) Bill, 2019 and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Bill, 2019 — look reasonable. The government and its supporters argue that the decisions merely seek to remove the “historical hurdles” holding back the nation’s progress. However, it’s the devil in the details that reveals the thinking behind the moves.

For instance, the decision on Article 370, which was anyway temporary and could have been done away with. But, as many pointed out, only by the J&K Constituent Assembly. The Article effectively meant laws enacted by Parliament needed the approval of the state government to enforce them in the state. Since there was no elected government in J&K, the Centre through a presidential decree birfucated the state and declared them Union Territories.

“I support abrogation of Article 370, as the opening words say it’s temporary, but only and only in accordance with provisions and methodology provided by the Constitution of India which mandates the consent of J&K State Assembly. Any other way is unconstitutional,” says Congress’s Jaiveer Shergill.

With respect to the implementation of the ‘one nation, one ration card’ scheme, for example, who would argue against a scheme that seeks to provide subsidised foodgrain to a poor migrant labourer who relocated from Bihar to Chennai? However, opposition to the seemingly generous scheme is over one crucial detail: Who will bear the cost for ration supplied to people from other states when Public Distribution System (PDS) is a state subject? Regional parties in Tamil Nadu have raised concerns that a single national ration scheme will derail the state’s universal PDS. The DMK has called it an attack on India’s federal structure, as PDS is a state subject.

Again, Modi’s idea of simultaneous elections to state assemblies and the Lok Sabha to prevent costly and lengthy elections. The idea was first floated in the Law Commission’s 170th report in 1999. More recently, in 2017, a NITI Aayog discussion paper, ‘Analysis of simultaneous elections: The what, why and how,’ made a similar case. According to it, the concept is not new. After the adoption of the Constitution in 1950, polls to the Lok Sabha and the state assemblies were held simultaneously every five years between 1951 and 1967, as the paper reveals. Interestingly, one of the most vocal supporters of the law panel’s report was veteran BJP leader LK Advani.

It is true that the first two elections in India after Independence were held simultaneously for both the Centre and the state Assemblies. However, over a period of time with the evolution of electoral politics, rise of regional powers and assertion of local identities the nature of polity itself changed.

So, why bring back something which the states look at suspiciously as a ploy to convert the elections into Presidential contest?

Besides fence-sitters like Naveen Patnaik-led Biju Janata Dal, there has been no support for the idea from any other political party till date.

According to Balveer Arora, chairman of Centre for Multilevel Federalism, the danger lies in the centralisation of power.

“The BJP-led NDA government’s experiment with federalism has nothing to do with its idea of nationalism. Nation is a socio-political concept, no one is fighting against the idea of a unified nation. The danger lies in the centralisation of power and authority being concentrated in one part of the federal structure,” he says.

States, Arora adds, are now getting increasingly disempowered.

Diversity lost in the process

Amid all these developments, what doesn’t escape the scrutiny is the fact that diverse needs of the many, which is the essence of India, gets subsumed into the need for uniformity.

The Britishers ruling India from England envisaged the federal system through the Montford reforms in 1918, under which they kept the overall levers of power, but gave freedom to individual princely states to address local issues more efficiently. The recommendations by Secretary of State for India Edwin Montagu and Viceroy Lord Chelmsford, were implemented in states, which were amenable to British rule.

The biggest attack on federalism, according to Kerala’s finance minister Thomas Isaac, is taking place through the financial sector. “The Centre is imposing limitations of the fiscal budget on states by curbing our borrowing power. Kerala’s borrowing power has been reduced by ₹6,000 crore. Now, it wants it to reduce the borrowing power to 2 per cent of the GDP.”

Besides, additional terms of references have been given to the Finance Commission. “This makes it clear that the Centre wants to reduce the State’s share in tax mop-up. GST is an additional burden,” says Isaac.

Another example of the Centre meddling with the powers of the state government was seen recently during a conclave of 11 Himalayan states that took place in Mussoorie last Sunday. The conclave, which was centrally sponsored, was attended by the finance minister, NITI Aayog chairman and chairman of the finance commission. A similar conclave of southern states is an event always attended only by the finance ministers.

“After all, we are talking about 11 votes in the GST council. Federalism has taken a whole new meaning under the NDA. It now about networking. These events are never attended by the finance commission. It is a body that holds its own interaction with states,” says Arora.

The role of the Finance Commission — which is supposed to define financial relations between Centre and State — in the event has raised question mark on its impartiality.

“Time and again, Modi government boasted that it is implementing the 14th Finance Commission, which increased the devolution of funds from 32 per cent to 42 per cent. But this has turned out to be a ‘Maha Jumla’ (big farce). In their manifesto, the BJP also promised to fiscal autonomy of states, but that has been thrown into the dustbin,” says Congress spokesperson Abhishek Singhvi. Singhvi says terms like cooperative federalism was the pivot of the BJP’s poll manifesto in 2014 and 2019, but the party has eroded federal autonomy and independence of states.

Despite the rising clamour, senior BJP leader Lalitha Kumaramangalam believes that federalism “is still alive and kicking”. “India is a union of states. Those who are anti-BJP seem to be running scared of both the party and prime minister’s rising popularity. The very fact that discussions such as this continue to take place is a sign that Indian democracy, both socio-political and in other spheres, is still very much alive.”

The passage of key bills recently, she says, clearly shows that the Opposition is disorganised and unable to stand up for what it believes in.

However, what has added to the anxiety of Kumaramangalam’s opponents is the haste shown by the Centre in pushing through key bills — such as the National Investigation Agency (NIA) Bill and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Bill, 2019 — without “proper scrutiny”.

While the NIA bill gives unbridled power to probe agency, the crucial amendments to the UAPA will now allow the Centre and states to designate individuals as terrorists and seize their property.

According to Revolutionary Socialist Party MP NK Premachandran, all bills coming to Parliament in recent times are an attempt to undermine our federal structure.

“Take for example, the Dam Safety Bill. All issues related to water and rivers are a state subject. Why does the Centre need to meddle with them? Again, the Consumer Protection Bill and Wage Code Bill have taken away the right of states to decide on remunerations. The National Medical Commission Bill is another example. Things that have been the prerogative of the states to decide have been done away with.”

The BJP’s plan for India, he says, is simple. “What it wants is a unitary, not a federal constitution.”