- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

The man who led to the Sphinx Intaglio in Kerala’s Pattanam

Archaeologists and scientists had long known that digging a little in Pattanam, a village on the banks of the Periyar river in Kerala, could help unearth a rich chapter in history. What stood in their way was the unwillingness of locals to let their land be dug up, until they knocked on the doors of Sukumaran Kalappuraparambil. The rest, as they say, is history. Recently, a group of...

Archaeologists and scientists had long known that digging a little in Pattanam, a village on the banks of the Periyar river in Kerala, could help unearth a rich chapter in history. What stood in their way was the unwillingness of locals to let their land be dug up, until they knocked on the doors of Sukumaran Kalappuraparambil. The rest, as they say, is history.

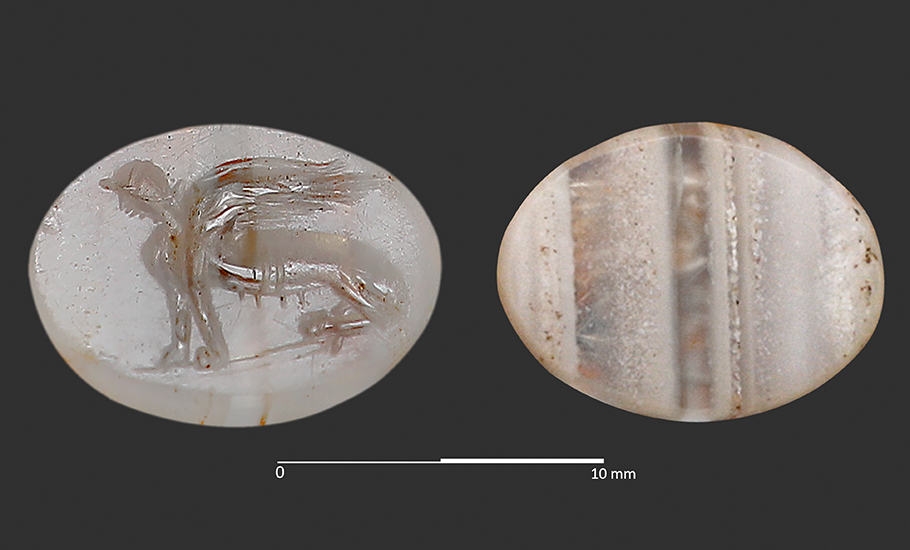

Recently, a group of heritage enthusiasts honoured Sukumaran, an artist who offered his land for archaeological excavations in Pattanam from where the Sphinx Intaglio (similar to the one worn by Roman emperor Augustus Caesar) was unearthed after 2,000 years, at the David Hall of Fort Kochi. Kalappuraparambil was honoured with a cheque of Rs 1 lakh as a token of appreciation for his willingness to allow the PAMA Institute for the Advancement of Transdisciplinary Archaeological Sciences to conduct archaeological excavation on his land which eventually led to the discovery of the Sphinx Intaglio, giving a new dimension to the trade and cultural relations between Pattanam and Rome.

Pattanam is considered a part of the ancient port called Muziris, which is mentioned in Roman, Greek and Sangam literature. On April 25, 2020, a team led by archaeologists located the oval-shaped zeal behind the kitchen of Sukumaran’s house in the northern sector of the Pattanam. As the team was about to leave, it was Sukumaran who encouraged them to continue the excavation by clearing a thick vegetation of tapioca plants on his land.

The Pattanam archaeological site is located in the Vadakkekara village of Paravur taluk, about 25 km from Kochi in the Ernakulam district of Kerala. This is a coastal site located in the delta of Periyar river, 4 km from the Arabian Sea coast. The word ‘Pattinam’ has its origins in the Prakrit language and it means a ferry, a port site or a commercial place. The location of Pattanam, as well as the materials unearthed here, point out the possibility that Pattanam could have been an integral part of the long lost legendary port of Muciri Pattinam or Muziris, mentioned in the Indian or European classical sources. Historians believe that as the hub of the trans-oceanic network, Muziris seems to have integrated the peninsular Indian region (Tamilakam) with the larger urbanisation process across the Indian Ocean.

As an artist, Sukumaran does oil portraits of people for a living. But the money that he earns from it is not enough to make ends meet. As many in the village refused permission to have their land dug up, it was Sukumaran who came forward and supported the excavation team. “I don’t have a proper income, particularly since the pandemic hit. I have a cow and the money that I get by selling its milk is my only source of income. It was a great moment in my life when the team found the Sphinx Intaglio from my backyard. I am grateful for this support. I am happy that I too have got a role in history,” said Sukumaran, after receiving the cash award.

Archaeological sites are often formed through long-term regular, sometimes sudden sediment depositions. Leaving little clues, the cultural pasts thus get buried underneath the soil. That is why 90 per cent of archaeological sites are identified by chance though new scientific methods are available to scan the earth. However, these sites can no longer be studied or conserved following the colonial policy of evicting people disregarding their affection for the land they lived on for generations, according to PJ Cherian, who led the excavation team in Pattanam.

“This is where legal, yet imaginative and scientifically motivated, initiatives are imperative to make the local communities the sentinels of the site. At Pattanam, as everywhere else, some are afraid to an extreme extent – a sort of phantom fear that a big calamity will befall them in case they permit archaeological excavations. This is a colonial legacy not easy to overcome. In 2020, when the Kerala Council for Historical Research [KCHR] denied PAMA institute excavation permits on government land, it was not only illegal but created confusion among villagers who otherwise were willing to permit digging,” he told The Federal.

RVG Menon, chairman of PAMA, was clear that instead of fighting a legal battle with KCHR or the government, PAMA should approach the villagers. “From 2007 till 2012, Pattanam research was mostly done on private lands only. In 2020 too, several villagers came forward. Sukumaran was one among them. With very limited land, he, in fact, plucked away his vegetables to provide us space to dig a trench on his land. Interestingly, the Sphinx was hiding below that area of his small plot,” he added.

The seal-ring was retrieved on April 25, 2020, a couple of days after the lifting of the national and state-level Covid-19 lockdowns, when the excavations were marginally restarted at Pattanam by the PAMA Institute for the Advancement of Transdisciplinary Archaeological Sciences. “The trench named PT 20 XLV was located in the kitchen shed at the backyard belonging to Sukumaran and his five sisters in the northern sector of the Pattanam archaeological mound. The tiny, oval-shaped ring-seal with a length of 1.2 cm is made of banded agate, a precious stone belonging to the Indian subcontinent, while the theme or symbol is of Mediterranean genesis,” said Cherian.

Pravitha PA, a student intern of the excavation team (also the niece of Sukumaran) picked it up from the wire-mesh net while sieving the soil. “I never knew the importance of the object when I first found it while digging. It was after I showed experts that I got to know of its importance,” said Pavitha, sharing her experience of finding the Sphinx first.

In Greek literature, according to Cherian, the Sphinx is always female and the only male reference is by Herodotus, but that was in relation to the Sphinx he had seen in Egypt. He said the Sphinx is described by the Greek tragic poets as a winged young woman with the body of a lion. The fullest description of Sphinx, however, is by the Pseudo-Apollodoros in a compendium of Greek mythology written between the third and second century BCE, as having a woman’s face and breasts, wings, a lion’s body and tail.

“Every day, as the story goes, she infested Thebes by seizing and devouring men, mostly young. As an escape offered to her victims, the Sphinx posed a riddle, which was composed on the advice of Muses (goddesses of arts and sciences), referring to three successive phases of human life. She posed the question, what walks in the morning on four feet and at noon with two and in the evening with three? Those who were unable to answer were seized and devoured irrespective of their status and position. The Thebans assembled every day to answer the riddle and get rid of the Sphinx until Oedipus solved the riddle by answering, ‘Man crawls on all fours as a baby, walks upright in the prime of life, and uses a staff in old age.’ The Sphinx then killed herself by jumping from her mountain or as in some other versions allowed to be killed by Oedipus,” he added.

Roman archaeologists and art historians say the Sphinx Intaglio excavated from Pattanam is a gem belonging to a seal-ring and can be considered a good quality example of Greco-Roman carving art. The Pattanam Sphynx is female not only because of the nipples, but also because of the hairstyle and the cheeks without beard. Cherian said though the myth of Sphinx was a subject of wide chronological range, the accuracy of the Pattanam gem style and carving technique suggest a chronology between the first and the second century CE. “Perhaps, some of these seal-rings travelled to the East with their owners, merchants or as merchandise,” he said.

Nipun Cherian, one of the organisers of the initiative to support Sukumaran, said the drive was to encourage the voluntary act of allowing temporary access by plot owners at Pattanam (and elsewhere) for excavations. The money was collected from heritage and history enthusiasts from various parts of Kerala,” said Nipun, of V4 Kochi.

The people who honoured and declared their affections to that poor family of Pattanam probably had an important message for all those waiting to join their known and unknown parents – empowering the local community to conserve and celebrate such a precious past that lay buried beneath their village.

“If the civil society is sensitive in the manner in which they respond to the well-being of the Sukumaran family, Pattanam can become a model to the world – it can become a site of cultural pilgrimage for the world,” said PJ Cherian.